by Victor A. Walsh

The two-lane paved road rises and falls, twists and turns, like a dangling rope, through the rugged Chihuahua hill country of northern Mexico. It’s amazing that one of Mexico’s most famous potters lives out here.

Shimmering in the stark desert light is the village of Mata Ortiz, home of Mexico’s renowned potter Juan Quezada. In the mid-day heat, the pueblo is deserted except for a few stray dogs roaming the dirt-rutted streets. Old adobe walls and ramshackle wooden fences are laced with clotheslines of brightly colored garments drying against a brown desert backdrop. Chickens and other farm animals, including a burro, shade themselves in the huts. A lame horse stands on three legs tethered to a large tree.

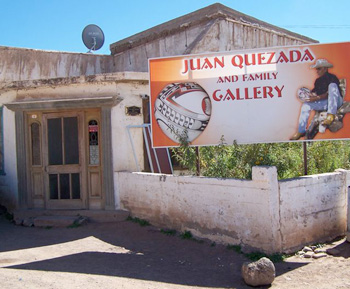

Quezada’s modest gallery is on the corner of the main street across from the historic, refurbished railroad line. As I enter, the artist, now in his early seventies, breezes in from the side room. Dressed in a faded tan cowboy hat, trim, medium height, bantamweight, looking fit as an Oklahoma rodeo wrangler, he welcomes me: “Buenas tardes, señor. Mi casa es su casa,” His rugged, suntanned face exudes a quiet humility and keen curiosity shaped by his many years of desert life. Later, he puts his arm around me, and Dick snaps my photo.

Quezada’s modest gallery is on the corner of the main street across from the historic, refurbished railroad line. As I enter, the artist, now in his early seventies, breezes in from the side room. Dressed in a faded tan cowboy hat, trim, medium height, bantamweight, looking fit as an Oklahoma rodeo wrangler, he welcomes me: “Buenas tardes, señor. Mi casa es su casa,” His rugged, suntanned face exudes a quiet humility and keen curiosity shaped by his many years of desert life. Later, he puts his arm around me, and Dick snaps my photo.

Juan Quezada has revived a lost ceramic tradition that had once thrived here among an indigenous people called the Paquimé. At its peak from 1200 to 1450, this civilization skirted the width of the Sierra Madre Mountains, encompassing the states of Chihuahua and Sonora. The spiral-formed polychromatic clay pots on display at the Museo Centro Cultural Paquimé in nearby Viejo Casas Grandes are objects of extraordinary beauty.

The pale sky-blue adobe walls in the front room are lined with ollas and vases, glazed in a rainbow of rust-red, brown, and eggshell hues and painted with intricate, geometric designs. Sunlight, streaming through the thin violet-blue curtains, casts an iridescent glow on them. I am mesmerized by their spiral, thin-walled shapes and meticulously painted and etched patterns.

The pale sky-blue adobe walls in the front room are lined with ollas and vases, glazed in a rainbow of rust-red, brown, and eggshell hues and painted with intricate, geometric designs. Sunlight, streaming through the thin violet-blue curtains, casts an iridescent glow on them. I am mesmerized by their spiral, thin-walled shapes and meticulously painted and etched patterns.

The long table in the adjoining room is covered with the rest of the family and neighbors’ pots, bowls, and figurines. Many of them, glazed in rust-red and cream brown pigments, feature water snakes and macaws—animals of great importance to the ancient Paquimé, but now extinct in the region.

I ask Juan if anyone has written a corrido, the ultimate Mexican tribute, about him and he immediately pulls a cassette out from a drawer. It has several ballads praising him for his contributions and calling him El Maestro. Beaming with pride, his wife Guille makes sure that he plays El Corrido de Juan Quezada sung by Ricardo Garcia for us.

My mind wanders as the room slowly fills with the lyrical beauty of Garcia’s baritone voice and guitar strumming. I gaze out the window. The heat glimmers over the parched, dust-colored land. Nothing seems to be alive except patches of creosote and agave clinging to the desert emptiness. How could such incredible artistic beauty come to exist in such a remote, hardscrabble place?

My mind wanders as the room slowly fills with the lyrical beauty of Garcia’s baritone voice and guitar strumming. I gaze out the window. The heat glimmers over the parched, dust-colored land. Nothing seems to be alive except patches of creosote and agave clinging to the desert emptiness. How could such incredible artistic beauty come to exist in such a remote, hardscrabble place?

The freedom and joy of discovery, I begin to realize, lies not in seeing new places, but in seeing things in new ways. The desert’s beauty lies in its austerity-—the spiny, oddly shaped plants, stark light, brilliant colors, and rich seams of clay. The texture, shapes, and colors of Quezada’s pots and vases convey in some strange but fascinating way its ambiance. The desert is at the core of Quezada’s existence.

He grew up poor leaving school at twelve to collect firewood and herd sheep in the hills above the village. While gathering firewood, he stumbled on some pottery shards from in a mountain cave, a Paquimé burial site.

“The first time I saw those pieces,” Juan tells me in Spanish, “I knew I had found a hidden treasure. I knew that the ancient ones must have found the materials here.” Over many years, he has patiently experimented with different clays, pigments, drawing and firing techniques to make ollas or pots with the ancient culture’s iconography and design.

“The first time I saw those pieces,” Juan tells me in Spanish, “I knew I had found a hidden treasure. I knew that the ancient ones must have found the materials here.” Over many years, he has patiently experimented with different clays, pigments, drawing and firing techniques to make ollas or pots with the ancient culture’s iconography and design.

He did this without any training or exposure to an artistic tradition or art community. “Nobody taught me. Nobody knew about the ancient ones when I was a boy,” he says.

The story could have ended here, lost in the buried memory of a poor village, but it did not because of young Quezada’s artistic genius, obsessive curiosity, and unlikely friendship with the American art dealer and anthropologist Spencer MacCallum that would change the fortune of the little town and shape an artistic legacy whose reach is still unknown.

Like a tale out of the Wizard of Oz, it began in 1976 when MacCallum stopped off at a second-hand swap shop in the New Mexico border town of Deming where he bought three unsigned pots. Intrigued by their intricate beauty and wondering if they were pre-Columbian in origin, he embarked on an adventure south that would take him to Mata Ortiz and the unknown potter.

Like a tale out of the Wizard of Oz, it began in 1976 when MacCallum stopped off at a second-hand swap shop in the New Mexico border town of Deming where he bought three unsigned pots. Intrigued by their intricate beauty and wondering if they were pre-Columbian in origin, he embarked on an adventure south that would take him to Mata Ortiz and the unknown potter.

A friendship quickly followed, and over the next six years, MacCallum provided Juan with money to work full-time at his craft, while he set up exhibits in the United States to premiere Juan’s work. “His arrival was a gift from God, a miracle,” according to Quezada.

Mata Ortiz today is the center of a bustling ceramic cottage industry. It attracts traders, collectors, gallery owners, potters and tourists. About one-fourth of its 2,600 inhabitants earn their livelihoods as potters—a significant number of them trained by Quezada himself, while others have developed their own unique styles and techniques.

The homes, some humble brick adobes; others larger cinder-block buildings, resonate with an infectious warmth and vitality for work. Children breeze in and out as if flying on broomsticks. Pots and vases line oilcloth-covered tables. I look over the shoulders of men and women as they shape, polish and paint at tiny sunlit work stations. They shape the lower portion of the object in a plaster mold, place a single coil of clay atop it, and then by hand work the clay upwards to form their thin-walled bowls, jars, and pots.

The homes, some humble brick adobes; others larger cinder-block buildings, resonate with an infectious warmth and vitality for work. Children breeze in and out as if flying on broomsticks. Pots and vases line oilcloth-covered tables. I look over the shoulders of men and women as they shape, polish and paint at tiny sunlit work stations. They shape the lower portion of the object in a plaster mold, place a single coil of clay atop it, and then by hand work the clay upwards to form their thin-walled bowls, jars, and pots.

A piece of hacksaw blade is used to smooth the surface. Objects are dried outside and then stone polished and sanded smooth without glazing. Hand-made kilns or just an inverted galvanized bucket buried in dried cow chips or cottonwood bark is used to fire the pots. Paints are made from minerals collected from rim-rock hillsides and nearby arroyos. The delicate, long flowing designs of the pots and ollas are painted with brushes made from children’s hair or etched.

Today, one of Quezada’s pots can sell for thousands of dollars. In 1999, he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, Mexico’s highest award given to a living Mexican-born artist.

Today, one of Quezada’s pots can sell for thousands of dollars. In 1999, he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, Mexico’s highest award given to a living Mexican-born artist.

His new home, a ranch house, stands on a hilltop overlooking the pueblo. He calls the place Ranchito Escondido, his hide-out. The property includes the land where he used to gather firewood. It has a rich vein of white clay, which he shares with other village potters. “Every where the sun shines is for everyone,” he says. A profound love of family and place, his belief in preserving a cultural heritage is what keeps this acclaimed artist rooted here.

His eldest son Arturo, brother Nicholas, and sisters Lydia, Genoveva, and Consolación have all become master potters. The hills, dark and barren, hold the materials of his craft and Quesada’s identity. He remains who he has always been: a potter who believes in miracles.

If You Go:

Getting There:

♦ The nearest large city, Nuevo Casas Grandes, has no commercial air service, but does have facilities for private planes.

Getting Around:

♦ The best way to get to Mata Ortiz is by car. The last eight miles of the road between the old pueblo of Casas Grandes (three miles outside of Nuevo Casas Grandes) and Mata Ortiz was recently graded and paved, allowing vehicles without overdrive to traverse the road.

♦ Vans can be rented in Nuevo Casas Grandes for groups. Contact Norma Delia Solis (694-0111 or 694-4888; her email is americantours@paquime.com.mx at Viajes American Tours, Avenida Hidalgo #601-B.

♦ Taxis (called sitios) from Nuevo Casas Grandes to Mata Ortiz cost about US $40 one-way or $50 round trip, plus $10/hour (negotiable) for waiting.

♦ Buses run daily between Nuevo Casas Grandes and Mata Ortiz.

Attractions:

♦ Among the attractions in Casas Grandes is the excavated prehistoric ruin of Paquimé. One of the most important prehistoric sites in northern Mexico, this commercial-religious center’s sphere of influence extended throughout Chihuahua and Sonora between 1200-1450A.D.

♦ The museum at the Centro Cultural Paquimé houses an outstanding collection of Paquimé artifacts, including ceramics, jewelry, fabrics, and stone masonry. Text panels are in English and Spanish.

Accommodations:

♦ The art gallery and bed and breakfast Las Guacamayas (“The Macaws”) is near the museum. It is owned by Mayté Luján.

♦ A block from the plaza is Spencer and Emi MacCallum’s La Casa del Nopal.

♦ In Mata Ortiz there is The Adobe Inn, known locally as “the hotel”, Marta Veloz’s Casa de Marta, and the Posada de Las Ollas.

For More Information:

♦ An excellent newsletter on the Mata Ortiz region – Mata Ortiz calendar.

♦ See also The Renaissance of Mata Ortiz

♦ Frontline World’s The Ballad of Juan Quezada

About the author:

Victor A. Walsh spends his time when he’s productively unemployed prowling forgotten or unusual destinations looking for stories that connect a place and its people to their remembered past. His historical essays and travel stories have appeared in the Christian Science Monitor, American History, Literary Traveler, California History, Rosebud and Sunset, among other publications.

Photos are by Dick Davis:

Juan Quezada’s Gallery

Lame horse

Front Room of Gallery

Author Victor Walsh and Juan Quezada

Entering Mata Ortiz

Center Cultural Paquimé Casas Grandes Museo

Mata Ortix Pottery in nearby Nuevo Casas Grandes shop

Plastered Mud Walls at Nearby Paquimé Casas Grandes

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts. I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had. Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.

There are places that tell your body and mind to slow down; to let the world come to you in unhurried steps. Places as beautiful as they are restful, as intrinsically informative as a guided tour yet far from the madding crowd.

There are places that tell your body and mind to slow down; to let the world come to you in unhurried steps. Places as beautiful as they are restful, as intrinsically informative as a guided tour yet far from the madding crowd. Though frequent visitors to the island this trip was a first for we had rented an oceanside cabin at Overbury Farm Resort. Still in the family of the original 1909 homesteader Geraldine Hoffman the farm, which originally gained renown for its eggs, became a resort in the 1930’s and pursues that legacy with manored elegance to this day. Our self-contained, modern cabin was a short forest walk to the gracefully aging and carefully tended manor house on Crescent Point, which owns a magnificent setting and ocean view, set amidst lawn, gardens and trees.

Though frequent visitors to the island this trip was a first for we had rented an oceanside cabin at Overbury Farm Resort. Still in the family of the original 1909 homesteader Geraldine Hoffman the farm, which originally gained renown for its eggs, became a resort in the 1930’s and pursues that legacy with manored elegance to this day. Our self-contained, modern cabin was a short forest walk to the gracefully aging and carefully tended manor house on Crescent Point, which owns a magnificent setting and ocean view, set amidst lawn, gardens and trees.

Owner Norm Kasting told us of a short cut trail through the forest to St. Margaret’s Cemetery and from there to the Capernwray grounds which cut off a good 30 minutes in our trek to the Telegraph Harbour Marina and Pub. As it is our wont to walk and explore we found our way to the cemetery and read, amid the tended lawn setting, how it was donated as a cemetery by early Island resident Henry Burchell in 1927. Its turf was even earlier turned to welcome the remains of a Burchell in 1924. It has since become the final resting place of a number the Overbury Farm-owning family, including pioneering Geraldine Hoffman.

Owner Norm Kasting told us of a short cut trail through the forest to St. Margaret’s Cemetery and from there to the Capernwray grounds which cut off a good 30 minutes in our trek to the Telegraph Harbour Marina and Pub. As it is our wont to walk and explore we found our way to the cemetery and read, amid the tended lawn setting, how it was donated as a cemetery by early Island resident Henry Burchell in 1927. Its turf was even earlier turned to welcome the remains of a Burchell in 1924. It has since become the final resting place of a number the Overbury Farm-owning family, including pioneering Geraldine Hoffman. A gateway opened to the grounds of Capernwray and access to wide grinning Preddy Bay beach where you can wander and explore with tended grounds behind and Vancouver Island panorama before. Capernwray asks that if you wish to enjoy walking their idyllic grounds that you check in at their office behind Preddy Hall. The whitewashed hall stands singularly elegant at the centre of the grounds. And walking their grounds is worth it. There are cared-for lawns with gardens, ponds and visiting Canada Geese, sedate Holstein cattle dotting the greens and views out to Chemainus from whence you can spot the ferry leisurely making its endless crossing. Capernwray offers the opportunity to dine at their hall, which dates back to 1927, along with the students. (Call to reserve 250-246-9440).

A gateway opened to the grounds of Capernwray and access to wide grinning Preddy Bay beach where you can wander and explore with tended grounds behind and Vancouver Island panorama before. Capernwray asks that if you wish to enjoy walking their idyllic grounds that you check in at their office behind Preddy Hall. The whitewashed hall stands singularly elegant at the centre of the grounds. And walking their grounds is worth it. There are cared-for lawns with gardens, ponds and visiting Canada Geese, sedate Holstein cattle dotting the greens and views out to Chemainus from whence you can spot the ferry leisurely making its endless crossing. Capernwray offers the opportunity to dine at their hall, which dates back to 1927, along with the students. (Call to reserve 250-246-9440). A stroll along Foster Point Road to the south of the island takes you past a massive Arbutus tree compelling the road to go around it. Grand as it is it is but second best to another, which rests near the community hall, and is acclaimed the largest Arbutus in B.C. A spider network of paved and unpaved roads offers up miles of leisurely strolling and exploring.

A stroll along Foster Point Road to the south of the island takes you past a massive Arbutus tree compelling the road to go around it. Grand as it is it is but second best to another, which rests near the community hall, and is acclaimed the largest Arbutus in B.C. A spider network of paved and unpaved roads offers up miles of leisurely strolling and exploring. A quiet inland hike can be picked up near the one room school house. Here the solitude of an enveloping forest can hush the busiest of minds.

A quiet inland hike can be picked up near the one room school house. Here the solitude of an enveloping forest can hush the busiest of minds.

Back in the early 1900’s, Olcott Beach was a resort area. When a trolley line was put in place between the towns of Lockport and Olcott in 1900, summer visitors flocked to the beach to enjoy the cool breezes of Lake Ontario and entertainment. Also vacationers arrived by steamship. During the early years of the 1900’s, over 100,000 tourists arrived yearly.

Back in the early 1900’s, Olcott Beach was a resort area. When a trolley line was put in place between the towns of Lockport and Olcott in 1900, summer visitors flocked to the beach to enjoy the cool breezes of Lake Ontario and entertainment. Also vacationers arrived by steamship. During the early years of the 1900’s, over 100,000 tourists arrived yearly.

When we parked near the shops, we immediately heard the “oom-pa-pa” of a carousel’s Wurlizer Band organ. The Olcott Beach Carousel Park was developed in 2003-2004 by local volunteers who raised funds for building a vintage amusement park.. It features an old time Herschell-Spillman two-row carousel and a few other kiddie rides for only 25 cents a ride! They can do this because the park is staffed by volunteers and is incorporated as a nonprofit organization. When you enter this quaint park you feel like you are going back in time to around 1945.

When we parked near the shops, we immediately heard the “oom-pa-pa” of a carousel’s Wurlizer Band organ. The Olcott Beach Carousel Park was developed in 2003-2004 by local volunteers who raised funds for building a vintage amusement park.. It features an old time Herschell-Spillman two-row carousel and a few other kiddie rides for only 25 cents a ride! They can do this because the park is staffed by volunteers and is incorporated as a nonprofit organization. When you enter this quaint park you feel like you are going back in time to around 1945. After a stroll through the mini-boardwalk and the park, we went around the corner to eat at the Mariner’s Landing restaurant. We chose to eat inside due to the heat that evening. But we could have eaten on an outdoor upper deck which offers a stunning view of Lake Ontario and nearby Krull Park. The inside was filled with nautical decor, especially on an upper ledge that ran all the way around the dining room. It was filled with models of ships, lighthouses, sea captains, and other knick-knacks. They were fascinating to look at.

After a stroll through the mini-boardwalk and the park, we went around the corner to eat at the Mariner’s Landing restaurant. We chose to eat inside due to the heat that evening. But we could have eaten on an outdoor upper deck which offers a stunning view of Lake Ontario and nearby Krull Park. The inside was filled with nautical decor, especially on an upper ledge that ran all the way around the dining room. It was filled with models of ships, lighthouses, sea captains, and other knick-knacks. They were fascinating to look at.

After our meal we needed to walk off some calories and wandered across the narrow street into the beautiful 325-acre Krull Park. The park overlooks the lake in the area where the old Grand Hotel once stood. We didn’t go down the steep stone step pathway to the beach below where the swimming area is, but enjoyed the view from above. The park is pleasantly arranged with benches, picnic areas, and pavilions. We heard that over the summer several festivals take place at the park. Across Main St. is another section of the park. In a drive-by, we could see busy recreation fields and courts that were full of kids playing sports, along with spectators. A cheerleading squad was practicing within sight of the street also.

After our meal we needed to walk off some calories and wandered across the narrow street into the beautiful 325-acre Krull Park. The park overlooks the lake in the area where the old Grand Hotel once stood. We didn’t go down the steep stone step pathway to the beach below where the swimming area is, but enjoyed the view from above. The park is pleasantly arranged with benches, picnic areas, and pavilions. We heard that over the summer several festivals take place at the park. Across Main St. is another section of the park. In a drive-by, we could see busy recreation fields and courts that were full of kids playing sports, along with spectators. A cheerleading squad was practicing within sight of the street also.

by Connie Pearson

by Connie Pearson  Driving into town, the first logical stop is the Dickson House at 150 E. King Street, which has Civil War significance and now serves as the Orange County Visitor Center. Park your car and see a 7-minute video giving an overview of Hillsborough’s history. Arrange for a guided tour, ask for information about restaurants, shopping, and town events, or purchase a walking tour booklet for $4.00. Make note of the public restrooms available on the grounds. The walking tour will take you past 46 well-documented structures, and 5 more are within a short drive. Most of the homes and offices are privately owned, but guided tours are available for Ayr Mount, Burwell School, and the gardens of Montrose.

Driving into town, the first logical stop is the Dickson House at 150 E. King Street, which has Civil War significance and now serves as the Orange County Visitor Center. Park your car and see a 7-minute video giving an overview of Hillsborough’s history. Arrange for a guided tour, ask for information about restaurants, shopping, and town events, or purchase a walking tour booklet for $4.00. Make note of the public restrooms available on the grounds. The walking tour will take you past 46 well-documented structures, and 5 more are within a short drive. Most of the homes and offices are privately owned, but guided tours are available for Ayr Mount, Burwell School, and the gardens of Montrose.

During a tour of The Burwell School Historic Site, you will hear many stories about the Burwell family, particularly wife and mother Anna Burwell. She was the very accomplished and well-educated wife of Robert, minister of Hillsborough Presbyterian Church. She did such an impressive job of educating her own 12 children, she drew the attention of a local doctor who asked her to teach his daughter as well. Anna Burwell saw that as an opportunity to supplement her husband’s meager salary. From that small beginning, she went on to oversee the educations of more than 200 young women from 1837-1857.

During a tour of The Burwell School Historic Site, you will hear many stories about the Burwell family, particularly wife and mother Anna Burwell. She was the very accomplished and well-educated wife of Robert, minister of Hillsborough Presbyterian Church. She did such an impressive job of educating her own 12 children, she drew the attention of a local doctor who asked her to teach his daughter as well. Anna Burwell saw that as an opportunity to supplement her husband’s meager salary. From that small beginning, she went on to oversee the educations of more than 200 young women from 1837-1857. A fascinating side story from those school years has ultimately drawn greater attention. A household slave girl named Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly worked strenuously for Mrs. Burwell. Although “Lizzie” had a harsh life, she eventually bought her freedom and became an accomplished dressmaker with such famous clients as Mrs. Robert E. Lee and Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. Mrs. Lincoln invited Lizzie to live in the White House and be her personal dresser. In that role she also became Mrs. Lincoln’s confidante, much of which is chronicled in Keckly’s book

A fascinating side story from those school years has ultimately drawn greater attention. A household slave girl named Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly worked strenuously for Mrs. Burwell. Although “Lizzie” had a harsh life, she eventually bought her freedom and became an accomplished dressmaker with such famous clients as Mrs. Robert E. Lee and Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. Mrs. Lincoln invited Lizzie to live in the White House and be her personal dresser. In that role she also became Mrs. Lincoln’s confidante, much of which is chronicled in Keckly’s book

You will probably work up an appetite with all of that walking. If so, Saratoga Grill at 108 S. Churton Street, is a delicious choice. New England clam chowder, Honey Almond Salmon, and scones are specialties. Blackened scallops, salads with house-made dressings, peppered swordfish, or the broiled seafood platter are other savory options. Every dish bursts with flavor. Doors open at 11:30 a.m. Arrive about that time. It will be completely full by 12:30.

You will probably work up an appetite with all of that walking. If so, Saratoga Grill at 108 S. Churton Street, is a delicious choice. New England clam chowder, Honey Almond Salmon, and scones are specialties. Blackened scallops, salads with house-made dressings, peppered swordfish, or the broiled seafood platter are other savory options. Every dish bursts with flavor. Doors open at 11:30 a.m. Arrive about that time. It will be completely full by 12:30. Frances Mayes, author of Under the Tuscan Sun, recently described Hillsborough this way: “After only two years, Hillsborough seems like the home I never left. When my family and I decided to move to North Carolina after decades in San Francisco, we kept hearing from friends in this area, ‘You must move to Hillsborough — that’s where all the writers and artists live.’ Being writers ourselves, we were magnetized by the idea of a town where creativity thrives, and, having grown up in a small town in Georgia, I wanted to return to a place with an intense sense of community. By great good luck, I found both, and more.”

Frances Mayes, author of Under the Tuscan Sun, recently described Hillsborough this way: “After only two years, Hillsborough seems like the home I never left. When my family and I decided to move to North Carolina after decades in San Francisco, we kept hearing from friends in this area, ‘You must move to Hillsborough — that’s where all the writers and artists live.’ Being writers ourselves, we were magnetized by the idea of a town where creativity thrives, and, having grown up in a small town in Georgia, I wanted to return to a place with an intense sense of community. By great good luck, I found both, and more.”