by Peter Kwong

I was mesmerized by a pile of stone sitting inside the brow of a herring skiff. I asked myself this seemingly silly question “ Did Haida Indians get their fish with stones?”

Next to the boat my Haida Indian friend Scott was working on a bench filleting a dozen of King Salmon. He was very much absorbed in his task and oblivious of my presence behind him. Once in a while I observed he would raise his head, cock his nose and squint his eyes to watch vigilantly over the ocean in front of him. It was low tide on the beach with children playing and gathering gigantic shell fish and mussels. Another silly question crossed my mind “Do the great white sharks roam in this remote part of the Pacific Northwest?”

Next to the boat my Haida Indian friend Scott was working on a bench filleting a dozen of King Salmon. He was very much absorbed in his task and oblivious of my presence behind him. Once in a while I observed he would raise his head, cock his nose and squint his eyes to watch vigilantly over the ocean in front of him. It was low tide on the beach with children playing and gathering gigantic shell fish and mussels. Another silly question crossed my mind “Do the great white sharks roam in this remote part of the Pacific Northwest?”

Here I was on a late morning sitting on the front porch of a beach front property with a commanding ocean view. I had stayed the previous night inside my friend’s family modest if not slightly dilapidated seaside bungalow. As I sipped a murky stale coffee I tried to analyze why everything appeared topsy-turvy to me since arrival at Masset Indian reserve, Queen Charlotte Island.

“Bungalows”- isn’t that an architectural platform invented by the East Indian and brought to the new world by the British? Yet on that long stretch of beach I found that only Bill Reid, the rich and famous totem carver, lives in a traditional long house. Everyone else lived in plain “million dollar view” bungalows on the reserve.

I also felt a little short changed not able to experience an enchanting evening lit up by candle fish. My consolation was to discover that eulachon, a fatty finger size smelt, used traditionally as candle is actually quite tasty. The native had a way to preserve the fish as food staple for the harsh winter by separating the oil and salting the flesh. The processed eulachon can then be preserved without refrigeration. When the time come for the fish is to be consumed the extracted oil is added back onto the dehydrated meat over wild rice. Unlike lox, the cold smoke salmon, eulachon was not prized by the European settlers and hence remained much unknown to the rest of the world.

My stomach did not agree well with the seaweed samosa offered to me at my previous dinner. Coastal people on both side of the pacific consume seaweed as part of the daily food staple. Unlike the Japanese who ground dry seaweeds into sheet for sushi rolls, the native on this side preferred deep fried seaweed sprinkled with salt into a shape like a East Indian samosa.

I was also intrigued to discover that bringing “meat” to the table is a children job in this part of the world. In this bountiful land the bears are huge, ravens are super-sized , the local sitka deer are exceptional small animals. Deer hunting meant children played in the backyard, corralled and wrestled a roaming deer to the ground and clubbed the animal with a nearby stone to bring venison for dinner. If it is possible for kids to hunt on land with stone, is it not too far fetched to believe one can catch fish with stone at sea?

But what flabbergasted me was the absence of a single erected totem pole on that long-stretch of beach on the reserve. Since the beginning of time the people of Haida Gwaii have been carving totem poles as sacred monument to tell the story of it people- folklore, myths and customs. When their huge collection of totem poles were eradicated by the missionaries for preparation of new life separated from their pagan gods, the Haida nation lost bearing of their past, required to reconcile with a integrated present of bungalows, electricity and other amenities of the modern world and ponder their unknown future. Slowly I began to understand the dichotomy split inside my head between my expectation of Haida Gwaii as depicted in Emily Carr paintings at the Vancouver Art Gallery to the super-reality I encountered on the ground.

But what flabbergasted me was the absence of a single erected totem pole on that long-stretch of beach on the reserve. Since the beginning of time the people of Haida Gwaii have been carving totem poles as sacred monument to tell the story of it people- folklore, myths and customs. When their huge collection of totem poles were eradicated by the missionaries for preparation of new life separated from their pagan gods, the Haida nation lost bearing of their past, required to reconcile with a integrated present of bungalows, electricity and other amenities of the modern world and ponder their unknown future. Slowly I began to understand the dichotomy split inside my head between my expectation of Haida Gwaii as depicted in Emily Carr paintings at the Vancouver Art Gallery to the super-reality I encountered on the ground.

The Canadian Forces Station (CFS) is located across the highway up on the foothill on the other side of the Indian reserve. It was originally built in 1942 as a Naval Radio Station (NRS) to look out for intruders from Imperial Japan. After the war the detachment operated as an HFDF intercept station of NORAD. When I asked Major LeMay what the motto of the station ‘SINE DUBIO SINE MORA‘ meant, he explained “’Without doubt without delay.’ Canada will declare sovereignty by scrambling jets to chase off Russian planes once they enter into our airspace.” And then he pointed down to the beach and commented, “Every time when float planes operated by exotic fishing charter swooped down into water near the reserve for trophy size salmon, the Indians sent their speed boats out to sea and threw rocks to chase off the intruding fishermen. In a quixotic way this is how indigenous native declared their sovereignty!”

That somehow explained to me about that mysterious pile of stones.

Full Day Queen Charlotte Kayak and Walking Tour from Picton

If You Go:

General Information: www.gohaidagwaii.ca

BC Government Web Site: www.hellobc.com/haida-gwaii-queen-charlotte-islands.aspx

Canadian Forces Station: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CFS_Masset

Haida Gwaii – Raven and the First Men video:

Celebration in Old Massett (Haida dancing) video:

Photo Credits:

Haida Heritage Centre by Christian and Kristie via Flickr

Haida fishing by Graham Richard / CC BY-SA

Haida totem poles by Karen Neoh / CC BY

About the author:

Peter Kwong was born and raised in Hong Kong. He came to Canada at the age of seventeen to pursue a liberal arts education at Simon Fraser University. A long time resident of Vancouver, Peter is is now retired and able to spend more time on his passion for travel and adventure.

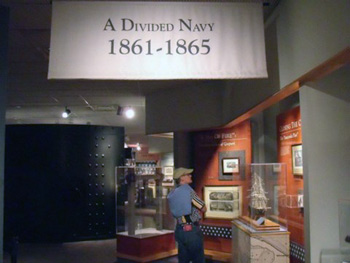

The light rail system’s Harbor Park Station leads right up to the Norfolk Tides’ baseball park, where minor leaguers strive to make it to the big leagues each season. But just behind the left field parking lot, a more important game was played out. These were areas where slaves strived to make it to freedom via some Virginia Underground Railroad sites of 150-plus years ago. Conspicuous yet unmarked pathways lead to these unkempt areas where once Higgins Wharf and Wright’s Wharf stood, overlooking the Elizabeth River. Now only fisherman can be found.

The light rail system’s Harbor Park Station leads right up to the Norfolk Tides’ baseball park, where minor leaguers strive to make it to the big leagues each season. But just behind the left field parking lot, a more important game was played out. These were areas where slaves strived to make it to freedom via some Virginia Underground Railroad sites of 150-plus years ago. Conspicuous yet unmarked pathways lead to these unkempt areas where once Higgins Wharf and Wright’s Wharf stood, overlooking the Elizabeth River. Now only fisherman can be found. Just a few blocks from “The Tide’s” Monticello Station, the Norfolk History Museum at the Willoughby-Baylor House can be found. Built in 1794, it has free entrance. The city’s history is extensively covered through pictures, maps, and aged artifacts including the occupation history of Union forces from 1862-1865. I learned about how whites evaded being drafted by getting African Americans to substitute for them in “Negro substitute” centers, some located in Norfolk. I discovered the violent aftermath when race riots were common after the war’s end, as blacks were striving to assert their new freedoms due to the 1866 Civil Rights Act. While ascending the second floor, I noticed some gripping black and white photos of Norfolk’s people and places during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Just a few blocks from “The Tide’s” Monticello Station, the Norfolk History Museum at the Willoughby-Baylor House can be found. Built in 1794, it has free entrance. The city’s history is extensively covered through pictures, maps, and aged artifacts including the occupation history of Union forces from 1862-1865. I learned about how whites evaded being drafted by getting African Americans to substitute for them in “Negro substitute” centers, some located in Norfolk. I discovered the violent aftermath when race riots were common after the war’s end, as blacks were striving to assert their new freedoms due to the 1866 Civil Rights Act. While ascending the second floor, I noticed some gripping black and white photos of Norfolk’s people and places during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For those who are into self-guided tours, I found the Cannonball Trail suitable for helping get more intimate with Norfolk. The walk takes explorers to potentially 43 different stately homes and other structures (dating from the 1790s until the early 1900s) around Norfolk’s waterfront, downtown, and Ghent neighborhood, offering views of such Civil War sites like the U.S. Customhouse, used as a dungeon by the Union Army.

For those who are into self-guided tours, I found the Cannonball Trail suitable for helping get more intimate with Norfolk. The walk takes explorers to potentially 43 different stately homes and other structures (dating from the 1790s until the early 1900s) around Norfolk’s waterfront, downtown, and Ghent neighborhood, offering views of such Civil War sites like the U.S. Customhouse, used as a dungeon by the Union Army. I learned through those particular exhibits that African Americans actually made up 16 percent of the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. I also didn’t know that Union General George McClellan attempted to cut off the rail hubs and water routes like an anaconda snake (i.e., “Anaconda Plan”) would use on its prey. This ultimately led to the eventually abandonment of the city by the Confederates.

I learned through those particular exhibits that African Americans actually made up 16 percent of the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. I also didn’t know that Union General George McClellan attempted to cut off the rail hubs and water routes like an anaconda snake (i.e., “Anaconda Plan”) would use on its prey. This ultimately led to the eventually abandonment of the city by the Confederates.

Over sixty years ago, two members of America’s Beat Generation did just that. First William Burroughs, then Jack Kerouac, came to Mexico City, searching for freedom, beauty and surreal inspiration in its storied, hallowed streets. They were drawn to a neighbourhood called “La Roma”, an enclave with a spirit that remains decidedly bohemian to this day, despite rising prices and gentrification spilling over from the neighbouring Colonia Condesa (“colonia” is the word that denizens of Mexico City, Chilangos, use for “neighbourhood”.)

Over sixty years ago, two members of America’s Beat Generation did just that. First William Burroughs, then Jack Kerouac, came to Mexico City, searching for freedom, beauty and surreal inspiration in its storied, hallowed streets. They were drawn to a neighbourhood called “La Roma”, an enclave with a spirit that remains decidedly bohemian to this day, despite rising prices and gentrification spilling over from the neighbouring Colonia Condesa (“colonia” is the word that denizens of Mexico City, Chilangos, use for “neighbourhood”.) La Roma is still the kind of place where a drag queen can live off the proceeds of her costume designs. Believe me, I met her. She lives in a small apartment off of Avenida Insurgentes and a red light shines from her window day and night, like a beacon, signalling to those who are wild and crazy and wonderfully artistic that they still can, unlike their Gringo counterparts, afford to live in a beautiful, central and historic neighbourhood.

La Roma is still the kind of place where a drag queen can live off the proceeds of her costume designs. Believe me, I met her. She lives in a small apartment off of Avenida Insurgentes and a red light shines from her window day and night, like a beacon, signalling to those who are wild and crazy and wonderfully artistic that they still can, unlike their Gringo counterparts, afford to live in a beautiful, central and historic neighbourhood. Today Calle Orizaba is one of the most beautiful in the neighbourhood, and the walk from 210 Orizaba north to the Insurgentes metro station is fantastic, taking you past historic homes, galleries, and the previously mentioned Plaza Luis Cabrera. It also passes the even lovelier Plaza Rio de Janeiro, where a replica of Michelangelo’s David towers above the square. Several intersecting streets are also worth exploring along the way, especially Colima and Durango, for their brightly coloured buildings, independent boutiques and art-filled watering holes. Casa Lamm, at the intersection of Orizaba and Alvaro Obregon is a cultural highlight, as is MUCA Roma on nearby Tonala street, a satellite gallery of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Located in an old historic home, it contains several floors of modern art, as well as one of the few free public washrooms in the area. These institutions are a testament to the dichotomy between historic preservation and gentrification that is now occurring in La Roma. On one hand they have kept art thriving and alive in the neighbourhood, and on the other, they have made it easier for businesses like American Apparel (Mexico City’s only outlet) to move in. It’s a double-edged sword, and you can pick your side amongst the al fresco dining options that surround nearby Plaza Rio de Janeiro. Orígenes Orgánicos, a corner café, represents the new, serving healthy vegetarian organic options on a private patio, bucking the trends in a country known for its love of meat. The dishes are not cheap by Mexican standards, about 90-120 pesos each (8-10 dollars), though they can provide welcome relief to travellers weighed down by a lack of plant-based options. For a new take on an old favourite, try their Nopales Huichapan: grilled cactus served with organic cheese, tomato and avocado. If you’re feeling more traditionalist, however, you can load up on birria tacos, made from stewed goat meat, around the corner for 6 pesos each, and eat them in the more democratic shade of the Plaza. Both are delicious.

Today Calle Orizaba is one of the most beautiful in the neighbourhood, and the walk from 210 Orizaba north to the Insurgentes metro station is fantastic, taking you past historic homes, galleries, and the previously mentioned Plaza Luis Cabrera. It also passes the even lovelier Plaza Rio de Janeiro, where a replica of Michelangelo’s David towers above the square. Several intersecting streets are also worth exploring along the way, especially Colima and Durango, for their brightly coloured buildings, independent boutiques and art-filled watering holes. Casa Lamm, at the intersection of Orizaba and Alvaro Obregon is a cultural highlight, as is MUCA Roma on nearby Tonala street, a satellite gallery of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Located in an old historic home, it contains several floors of modern art, as well as one of the few free public washrooms in the area. These institutions are a testament to the dichotomy between historic preservation and gentrification that is now occurring in La Roma. On one hand they have kept art thriving and alive in the neighbourhood, and on the other, they have made it easier for businesses like American Apparel (Mexico City’s only outlet) to move in. It’s a double-edged sword, and you can pick your side amongst the al fresco dining options that surround nearby Plaza Rio de Janeiro. Orígenes Orgánicos, a corner café, represents the new, serving healthy vegetarian organic options on a private patio, bucking the trends in a country known for its love of meat. The dishes are not cheap by Mexican standards, about 90-120 pesos each (8-10 dollars), though they can provide welcome relief to travellers weighed down by a lack of plant-based options. For a new take on an old favourite, try their Nopales Huichapan: grilled cactus served with organic cheese, tomato and avocado. If you’re feeling more traditionalist, however, you can load up on birria tacos, made from stewed goat meat, around the corner for 6 pesos each, and eat them in the more democratic shade of the Plaza. Both are delicious.

For a less trendy, more downhome perspective of La Roma, head to Roma Sur, which, for those of you who are Spanish-deficient, is the southern section of the neighbourhood. Centred around the Chilpancingo Metro station, Roma Sur is less pretty than its northern neighbour, but offers many cheaper, more authentically Latin American experiences. Right outside the Chilpancingo Metro station, on Avenida Baja California, La Espiga, a Mexican bakery, serves up delicious pastries for around five pesos, and fresh out of the oven Bolillos (buns) for even less. Walk a few blocks east and you hit Calle Medellin, home to Colombian restaurants and bakeries, and the Mercado de Medellin, a huge indoor market where you can do your produce shopping, buy fresh juice, or, if you feel like it, sit down to a delicious meal of chilaquiles con longaniza or enchiladas verdes for less than four dollars.

For a less trendy, more downhome perspective of La Roma, head to Roma Sur, which, for those of you who are Spanish-deficient, is the southern section of the neighbourhood. Centred around the Chilpancingo Metro station, Roma Sur is less pretty than its northern neighbour, but offers many cheaper, more authentically Latin American experiences. Right outside the Chilpancingo Metro station, on Avenida Baja California, La Espiga, a Mexican bakery, serves up delicious pastries for around five pesos, and fresh out of the oven Bolillos (buns) for even less. Walk a few blocks east and you hit Calle Medellin, home to Colombian restaurants and bakeries, and the Mercado de Medellin, a huge indoor market where you can do your produce shopping, buy fresh juice, or, if you feel like it, sit down to a delicious meal of chilaquiles con longaniza or enchiladas verdes for less than four dollars.

I smiled at the typical mono-syllabic answer, but Amanda and I kept up our lines of questions. When pressed, he finally told us of the time he had been sent out in the middle of the night to find a group of Park Ranchers who’d gotten lost here in Canyon de Chelly (pronounced de Shay). He’d talked them down one cliff and walked them up another. He knows this place by heart, even in the dark.

I smiled at the typical mono-syllabic answer, but Amanda and I kept up our lines of questions. When pressed, he finally told us of the time he had been sent out in the middle of the night to find a group of Park Ranchers who’d gotten lost here in Canyon de Chelly (pronounced de Shay). He’d talked them down one cliff and walked them up another. He knows this place by heart, even in the dark. This is a rule that I can get behind, especially after Calvin pulled our 4×4 from the mud and told us about pulling hikers from of flash flood waters. But the guided-only rule isn’t just for safety. It’s a respect thing. The Navajo’s don’t want anyone else messing with their land. They’ve had enough of that. Bitter stories of conquistadors or explorers had made their way through my tours of the Zuni and Acoma pueblos, but Calvin’s story of The Long Walk hit me the hardest.

This is a rule that I can get behind, especially after Calvin pulled our 4×4 from the mud and told us about pulling hikers from of flash flood waters. But the guided-only rule isn’t just for safety. It’s a respect thing. The Navajo’s don’t want anyone else messing with their land. They’ve had enough of that. Bitter stories of conquistadors or explorers had made their way through my tours of the Zuni and Acoma pueblos, but Calvin’s story of The Long Walk hit me the hardest.

Kit Carson knew how to solve this canyon problem though. Fire. In 1863 his “Scorched Earth Campaign,” burned all Navajo property in and around the canyon was burned. Traditional hogan homes, peach trees, and grazing animals were all destroyed. With no crops, little food, and only the charred remains of their homes, Navajo’s fled up the walls of Canyon de Chelly. But without canyon protection, they were easy targets for Carleton and Carson’s men and the many Ute Indians who were working with the colonels. Navajos spotted were giving a choice to make at gunpoint: surrender or be shot on site. Although a few people escaped, the majority of the tribe surrendered. Kit Carson’s plan worked.

Kit Carson knew how to solve this canyon problem though. Fire. In 1863 his “Scorched Earth Campaign,” burned all Navajo property in and around the canyon was burned. Traditional hogan homes, peach trees, and grazing animals were all destroyed. With no crops, little food, and only the charred remains of their homes, Navajo’s fled up the walls of Canyon de Chelly. But without canyon protection, they were easy targets for Carleton and Carson’s men and the many Ute Indians who were working with the colonels. Navajos spotted were giving a choice to make at gunpoint: surrender or be shot on site. Although a few people escaped, the majority of the tribe surrendered. Kit Carson’s plan worked.

But Calvin knows all his grandma’s stories – even the sad ones. According to Navajo tradition, the grandmother chooses one grandchild (out of dozens, in Calvin’s case) to keep in the ancestral home and instruct in traditional Navajo ways. So as Calvin’s parents and siblings eventually left the enclosed walls of Canyon de Chelly for jobs in Gallup and Phoenix, Calvin stayed behind. He played in the prehistoric cliff dwellings high in the canyon walls and he tended to goats on the valley floor. He hunted skinwalkers and slept in hogans and learned from his grandmother. When he was twelve, the US government discovered that there was an un-schooled child living down in the canyon and officials came to take him to school at Fort Wingate. Upon overhearing that his long hair would be chopped off the next day, Calvin embarked on a mini-long walk of his own, finding his way back to his grandmother and those orange canyon walls. She had breakfast waiting for him.

But Calvin knows all his grandma’s stories – even the sad ones. According to Navajo tradition, the grandmother chooses one grandchild (out of dozens, in Calvin’s case) to keep in the ancestral home and instruct in traditional Navajo ways. So as Calvin’s parents and siblings eventually left the enclosed walls of Canyon de Chelly for jobs in Gallup and Phoenix, Calvin stayed behind. He played in the prehistoric cliff dwellings high in the canyon walls and he tended to goats on the valley floor. He hunted skinwalkers and slept in hogans and learned from his grandmother. When he was twelve, the US government discovered that there was an un-schooled child living down in the canyon and officials came to take him to school at Fort Wingate. Upon overhearing that his long hair would be chopped off the next day, Calvin embarked on a mini-long walk of his own, finding his way back to his grandmother and those orange canyon walls. She had breakfast waiting for him.

To get the furs to Fort William, the 90-pound bales of furs were loaded into 25-foot Northwest birch-bark canoes, along with the outpost’s agent and supplies needed for the trip, and paddled on the liquid highway by four to six voyageurs. Each canoe carried up to 1-½ tons of cargo and people. The canoes were developed by the Ojibway Indians in the area and the Northwest Company went to great lengths to keep their competition from having access to that flat-bottomed canoe, the perfect watercraft vehicle to navigate the shallow rivers and streams of Northern Minnesota and Lower Canada. The Hudson Bay and American Fur Companies use the less efficient “York” canoe.

To get the furs to Fort William, the 90-pound bales of furs were loaded into 25-foot Northwest birch-bark canoes, along with the outpost’s agent and supplies needed for the trip, and paddled on the liquid highway by four to six voyageurs. Each canoe carried up to 1-½ tons of cargo and people. The canoes were developed by the Ojibway Indians in the area and the Northwest Company went to great lengths to keep their competition from having access to that flat-bottomed canoe, the perfect watercraft vehicle to navigate the shallow rivers and streams of Northern Minnesota and Lower Canada. The Hudson Bay and American Fur Companies use the less efficient “York” canoe. The brigades coming in from the Yukon in the far west stayed about a week at Rendezvous before they had to start back to the outpost before the rivers froze. Those coming in from closer outposts, such as one of the Fond de Lac’s outpost on Minnesota’s Snake River (near modern day Pine City, MN), stayed longer.

The brigades coming in from the Yukon in the far west stayed about a week at Rendezvous before they had to start back to the outpost before the rivers froze. Those coming in from closer outposts, such as one of the Fond de Lac’s outpost on Minnesota’s Snake River (near modern day Pine City, MN), stayed longer. Today, you can experience Grand Rendezvous the second weekend of July each year or explore the fort anytime. I wanted to experience what is was like paddling a Nor’west canoe on the Kaministiquia River just as the voyageurs did in the early 1800s. Free 20-minute trips leave the wharf several times each day between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm. Don’t worry – each of the six to eight modern “voyageurs” per canoe must wear a lifejacket and learn the commands of paddling. Each canoe has a period-costumed experienced bowman in the front and a steersman in the back.

Today, you can experience Grand Rendezvous the second weekend of July each year or explore the fort anytime. I wanted to experience what is was like paddling a Nor’west canoe on the Kaministiquia River just as the voyageurs did in the early 1800s. Free 20-minute trips leave the wharf several times each day between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm. Don’t worry – each of the six to eight modern “voyageurs” per canoe must wear a lifejacket and learn the commands of paddling. Each canoe has a period-costumed experienced bowman in the front and a steersman in the back. Once back at the wharf, I walk toward the main gate leading into the fort. Just before going under the gate archway, on the right is a small voyageur encampment. One of the voyageurs just finished cooking some fish over the campfire. The voyageurs were not allowed to stay inside the fort palisade. The fort interior was reserved for gentlemen, such as clerks, bourgeois and tradesmen, along with the elite of the company – the company partners.

Once back at the wharf, I walk toward the main gate leading into the fort. Just before going under the gate archway, on the right is a small voyageur encampment. One of the voyageurs just finished cooking some fish over the campfire. The voyageurs were not allowed to stay inside the fort palisade. The fort interior was reserved for gentlemen, such as clerks, bourgeois and tradesmen, along with the elite of the company – the company partners. I scanned the room looking at his equipment and “medicines” and noticed a saw lying on a table. Doc explains the limb amputation process and that he used it as a last resort – the success rate is not good as only about one out of every two ever healed and lived. Most of the amputees succumbed to infection. Those requiring long-term convalescence were moved to the hospital on the other end of the square. An amputation ended the person’s employment as a voyageur. Voyageurs needed both strong arms to paddle for weeks on end and both strong legs to haul the equipment over portages, some as long as 14 miles.

I scanned the room looking at his equipment and “medicines” and noticed a saw lying on a table. Doc explains the limb amputation process and that he used it as a last resort – the success rate is not good as only about one out of every two ever healed and lived. Most of the amputees succumbed to infection. Those requiring long-term convalescence were moved to the hospital on the other end of the square. An amputation ended the person’s employment as a voyageur. Voyageurs needed both strong arms to paddle for weeks on end and both strong legs to haul the equipment over portages, some as long as 14 miles.

In the kitchen and bakery, three “cooks” are busy preparing fare for the noon meal. With fowl hanging and some already cooking in the reflector oven, one cook is breaking home-baked bread into pieces in preparation for making bread pudding. Another is cutting scallions as one ingredient for use in a prepared dish. With 1,200 in camp, it was a busy two months for the cooks keeping up with the hungry demands.

In the kitchen and bakery, three “cooks” are busy preparing fare for the noon meal. With fowl hanging and some already cooking in the reflector oven, one cook is breaking home-baked bread into pieces in preparation for making bread pudding. Another is cutting scallions as one ingredient for use in a prepared dish. With 1,200 in camp, it was a busy two months for the cooks keeping up with the hungry demands. Our final stop is at the Wintering House of Kenneth McKenzie and his family. McKenzie was the Northwest’s chief operating officer at Fort William. Officially established in 1784, NWC was actually a loosely knit coalition of independent traders based in Montreal that operated under an arrangement of agreements with fur traders and Indians in the interior. They never did have an official charter as did their rival the Hudson Bay Company. At the head of the company was Simon McTavish, a Scottish Highlander, who ran the company from its beginning until his death in 1804. Each summer for a couple of weeks, he would come out from Montreal to visit Fort William. In the Great Dining Hall, a room off to the side was always kept ready for his arrival. McTavish brought three of his nephews William, Duncan and Simon McGillivray into the fur business. William rose to head the company after his uncle’s death.

Our final stop is at the Wintering House of Kenneth McKenzie and his family. McKenzie was the Northwest’s chief operating officer at Fort William. Officially established in 1784, NWC was actually a loosely knit coalition of independent traders based in Montreal that operated under an arrangement of agreements with fur traders and Indians in the interior. They never did have an official charter as did their rival the Hudson Bay Company. At the head of the company was Simon McTavish, a Scottish Highlander, who ran the company from its beginning until his death in 1804. Each summer for a couple of weeks, he would come out from Montreal to visit Fort William. In the Great Dining Hall, a room off to the side was always kept ready for his arrival. McTavish brought three of his nephews William, Duncan and Simon McGillivray into the fur business. William rose to head the company after his uncle’s death. Northwest’s interior headquarters was not always located on the Kaministiquia River near Thunder Bay. Before 1803, their depot was located on the shore of Lake Superior. However, being a British company and with the border between the United States and Canada not yet drawn, they feared they would end up as part of the United States and end up paying large pay custom duties, so they moved north so they would be well inside Canada. It was a wise move as Grand Portage did end up in the United States. In 1821, the Northwest Company ceased to exist as they were swallowed up by the Hudson Bay Company, a chief rival of theirs since 1793.

Northwest’s interior headquarters was not always located on the Kaministiquia River near Thunder Bay. Before 1803, their depot was located on the shore of Lake Superior. However, being a British company and with the border between the United States and Canada not yet drawn, they feared they would end up as part of the United States and end up paying large pay custom duties, so they moved north so they would be well inside Canada. It was a wise move as Grand Portage did end up in the United States. In 1821, the Northwest Company ceased to exist as they were swallowed up by the Hudson Bay Company, a chief rival of theirs since 1793.