by Mari Kane

As we emerge from our van in front of the Jean-Michel Cousteau Fiji Islands Resort, I hear music. Outside, a Fijian guy is playing guitar and singing a welcome home song. Beside him, a Fijian woman is offering us colorful drinks with tiny umbrellas. I want to wave them away with an “aw garsh, ya shouldn’t have,” until I realize that every guest is serenaded upon arrival. After a ten-hour flight from Los Angeles and a one-hour flight in a six-seat plane from Nadi International Airport, their song is a symphony to our jet-lagged ears.

The five-star resort is a collection of thatched roof bures spread over a former coconut plantation on a lush peninsula on the island of Savusavu. Named for the son of the world’s most famous diver, the resort is unsurprisingly eco-friendly. Not only does it run a marine preserve in Savusavu Bay, it also employs a full-time marine biologist to guide visitors through its underwater backyard.

We arrived in mid-March 2010, one week after a category-four cyclone had torn through the Fijian islands and destroyed buildings, homes and roads. Driving from the tiny airport, we saw lots of damaged structures and broken tree limbs being chainsawed into manageable pieces. The once-verdant jungles, stripped of foliage and flowers, were tinged a mottled shade of brown. At the Cousteau resort we saw numerous downed trees, and a tour of the organic vegetable garden revealed a heartbreaking mess of broken seedlings. From the pier, we could see how the coral had taken on a variety of beige tones, and on the beach, piles of broken pieces had washed up, free for the guilt-free taking.

We arrived in mid-March 2010, one week after a category-four cyclone had torn through the Fijian islands and destroyed buildings, homes and roads. Driving from the tiny airport, we saw lots of damaged structures and broken tree limbs being chainsawed into manageable pieces. The once-verdant jungles, stripped of foliage and flowers, were tinged a mottled shade of brown. At the Cousteau resort we saw numerous downed trees, and a tour of the organic vegetable garden revealed a heartbreaking mess of broken seedlings. From the pier, we could see how the coral had taken on a variety of beige tones, and on the beach, piles of broken pieces had washed up, free for the guilt-free taking.

Still, the sun was high and the air was warm, and the Fijians kept saying “Bula, welcome home,” as if we’d returned to a place we’d been before. That cyclone suddenly seemed so last week.

The size of our oceanview bure rivaled our Vancouver apartment, with enough closet space to keep our stuff hidden. Two walls were plantation blinds, the domed ceiling thatched, and the entire bathroom earthy-tone tile. After being briefed on everything from the best way to keep mosquitos out and the various organized activities, we were given a foot bath and massage on our porch. Talk about a fine howdy do, this was an effective way to make a visitor feel welcomed home. It made me want to curl up on the beach with a good book.

The size of our oceanview bure rivaled our Vancouver apartment, with enough closet space to keep our stuff hidden. Two walls were plantation blinds, the domed ceiling thatched, and the entire bathroom earthy-tone tile. After being briefed on everything from the best way to keep mosquitos out and the various organized activities, we were given a foot bath and massage on our porch. Talk about a fine howdy do, this was an effective way to make a visitor feel welcomed home. It made me want to curl up on the beach with a good book.

But with so many things to do at Cousteau, who has time to lay on the beach? Every day offers something new. We starting several mornings with yoga on the beach, or if it rained, the group stretched in the children’s Bula Club among the giant chess pieces. Outfitted with snorkeling mask and fins, we took launches out on Savusavu Bay where I got my first look at a white-tipped shark. On another day, we rode a school bus across the island, high up to the Waisali Rainforest Reserve for a hike to a waterfall under which we swam in the clear pool of mountain spring water. The scene was like out of a movie.

Then there was the kava. Also known as kava-kava it’s made from the roots of the Piper methysticum plant and is used as a sedative and anesthetic. Here, kava is a ceremony, where ground kava root is mixed with water in a traditional wooden bowl and is scooped out in a coconut shell and passed from person to person. Before and after drinking the metallically vegetal-tasting juice, we are told clap once, which can be tricky when you’re holding a coconut shell full of kava in one hand.

Before, during and after dinner we were entertained by the Cousteau’s house combo, the Bula Band, a group of young men who sang and played guitars. These guys were big on kava and encouraged us to sing and drink along. Joining them became a great way to relax after a long day of, well – relaxing.

Before, during and after dinner we were entertained by the Cousteau’s house combo, the Bula Band, a group of young men who sang and played guitars. These guys were big on kava and encouraged us to sing and drink along. Joining them became a great way to relax after a long day of, well – relaxing.

To prevent our minds from going completely to mush, the resort presented stimulating ecologic-related programs each evening before dinner. One night, whale photographer Bryant Austin discussed his style of capturing high resolution pictures while free-diving among whales and he showed slides of his full-sized whale photographs, which his exhibits in whaling countries. Another evening, the resort’s resident marine biologist used video produced by Jean-Michel Cousteau to discuss the nature of sharks. From him we learned that sharks don’t actually bite people; they’re just getting a little taste. That’s a relief.

When it comes to dining, Cousteau is famous for its cuisine. The open-air Serenity dining room, overlooking the infinity pool, offers a menu of beautifully presented three-course meals on a fourteen-day rotation. So, if you stay two weeks you never eat the same thing twice.

On our first night, we were treated to a traditional Fijian feast, cooked mostly in the lovo – a fire pit lined with heat-resistant stones. All afternoon, the smoky savoriness wafted over the resort, piquing our appetites. The buffet included lovo-cooked pork, chicken, beef as well as a whole walu – or Spanish mackerel – and were augmented with chunks of baked taro, sweet potato and plantain, smoked to perfection.

On our first night, we were treated to a traditional Fijian feast, cooked mostly in the lovo – a fire pit lined with heat-resistant stones. All afternoon, the smoky savoriness wafted over the resort, piquing our appetites. The buffet included lovo-cooked pork, chicken, beef as well as a whole walu – or Spanish mackerel – and were augmented with chunks of baked taro, sweet potato and plantain, smoked to perfection.

What I loved the most was a dish called palusami. This is a mix of onion, tomato and other veggies wrapped in taro leaves and soaked in coconut milk. Coconut milk is a key ingredient in Fiji and is made fresh at the Cousteau resort. Cooked in the lovo, palusami is satisfying enough to turn me into a vegetarian.

The good eats are not limited to the Serenity dining room, however. True romantics can have a table set up at the end of the pier for more privacy, an arrangement we saw working nicely until the wind and rain forced a quick evacuation. The kitchen will also load a gas grill, tables and chairs into a boat and set up a full lunch on Naviavia Island out in the bay, an event that impressed the large party of Californians who participated.

The good eats are not limited to the Serenity dining room, however. True romantics can have a table set up at the end of the pier for more privacy, an arrangement we saw working nicely until the wind and rain forced a quick evacuation. The kitchen will also load a gas grill, tables and chairs into a boat and set up a full lunch on Naviavia Island out in the bay, an event that impressed the large party of Californians who participated.

The mellow Fijians who run the Cousteau resort have a gift for making guests feel at home. live in a nearby village and live off the land and sea. I asked our boat pilot – who doubles as a kayak wrangler and grounds keeper – how he liked working at Cousteau, and he laughed and said, “I can just pull off my shirt and jump in the water whenever I want. What can be better than that?”

Our waiter told us he had worked on Fiji’s big island and it was expensive and a tough place to live, “but here, I can pull down a coconut or catch a fish to eat and it’s free.” Sounds pretty idyllic to me, although the village suffered some big-time crop loss in the storm. To support the village, the resort requests donations for a fund to benefit their Fijian employees and their families. Assistant Manager Bart Simpson – his real name – told us the Fijian’s hospitality comes naturally. “A lot of the nice things they do, we don’t ask them. They just do it.”

Our waiter told us he had worked on Fiji’s big island and it was expensive and a tough place to live, “but here, I can pull down a coconut or catch a fish to eat and it’s free.” Sounds pretty idyllic to me, although the village suffered some big-time crop loss in the storm. To support the village, the resort requests donations for a fund to benefit their Fijian employees and their families. Assistant Manager Bart Simpson – his real name – told us the Fijian’s hospitality comes naturally. “A lot of the nice things they do, we don’t ask them. They just do it.”

By the end of our week we couldn’t pass up a fragrant massage in one of the spa bures on the beach, where the only sounds are lapping water, breezing palms and the breath of the Fijian masseuse as she rubs me down with floral-scented oils. Nor could we resist taking a couple of the kayaks out on the bay along Sauvusavu’s coastline, to see the vivid brownness of the shore and the beige coral through our glass bottoms.

The Cousteau resort may be seductive to couples, but from all appearances it’s also dynamite for families. The Bula Club spans a large swath near the vegetable gardens encompassing two freshwater pools with slides plus a mushroom pool for toddlers, a jungle gym, a sandbox, and two open-air club houses for doing art projects or playing giant chess. I saw a crowd of pre-adolescents going nuts on the deep-pool slide, and while their Fijian nanny stood close, occasionally calling admonishments, she pretty much let them cut loose.

The resort’s nannies are available all day, so parents can have time alone if they want. Although kids are not allowed in the Serenity dining room, families can dine together in an equally beautiful space on the other side of the infinity pool. This separation of kids and adults is not only a welcome respite from the noise and frenetic energy of children, it also make you appreciate them more.

The resort’s nannies are available all day, so parents can have time alone if they want. Although kids are not allowed in the Serenity dining room, families can dine together in an equally beautiful space on the other side of the infinity pool. This separation of kids and adults is not only a welcome respite from the noise and frenetic energy of children, it also make you appreciate them more.

One of my favorite times was when nannies brought the kids out on the resort pier to spot fish and coral in the morning’s low tides. The way they were mesmerized by the underwater life made me realize that for all our differences, one thing children and adults always have in common is the appreciation of nature. For this reminder alone, I loved having these kids around.

As we depart the Cousteau resort – rested, relaxed, tanned and well fed – we are again sung away by the bula guys and the managers. They make us feel that instead of going home, we are actually leaving it.

If You Go:

♦ Flights to Nadi International leave from Los Angeles four times per week via Air Pacific. The 10 hour flights range from $1,363 – 2,357 depending on the month.

♦ Flights to Savusavu from Nadi run several times per day and range from $246 – 527.

♦ Depending on the season and the bure chosen, rates for two adults start at $820 per night, including all meals, soft drinks, Fiji water, teas, coffee, the activities mentioned above, Bula Club for children and return vehicle transfers from the local airport.

♦ Additional charges apply to spa services, alcohol, diving equipment, island lunches and pier dinners.

♦ Read more about Fijian food at tastingroomconfidential.com/eatin-fijian

About the author:

Mari Kane is a writer, blogger and internet marketer based in Vancouver, BC. As a member of the BC Travel Writers Association, Mari won her trip to Fiji in a drawing at the BCTWA annual gala and is grateful to them and the PR Counsel at Tourism Fiji.

All photos by Mari Kane, © 2010.

My wife Annie and I are immersing ourselves in the history and culture of Hawaii’s less crowded “outer” shores, far from the lights and traffic of Waikiki. It is like opening a Russian doll, so many hidden dimensions are revealed. We keep getting vivid glimpses of long-vanished ways of life. It is a rich, diverse and sometimes shocking tableau, full of extreme contrasts. On the one hand, there is the fondly imagined paradise of dramatic geography, a sultry climate and beautiful native people. On the other, a history of brutal warfare and the oppressive traditional social system, in which commoners might be killed for stepping on the king’s shadow. On the Big Island, however, people were safe if they reached sanctuary within the walls and temples of the City of Refuge, now painstakingly restored.

My wife Annie and I are immersing ourselves in the history and culture of Hawaii’s less crowded “outer” shores, far from the lights and traffic of Waikiki. It is like opening a Russian doll, so many hidden dimensions are revealed. We keep getting vivid glimpses of long-vanished ways of life. It is a rich, diverse and sometimes shocking tableau, full of extreme contrasts. On the one hand, there is the fondly imagined paradise of dramatic geography, a sultry climate and beautiful native people. On the other, a history of brutal warfare and the oppressive traditional social system, in which commoners might be killed for stepping on the king’s shadow. On the Big Island, however, people were safe if they reached sanctuary within the walls and temples of the City of Refuge, now painstakingly restored.

Also surprising is how rapidly Hawaii changed after Captain Cook arrived in 1778. By the 1820s, Lahaina was a bustling center for whalers and missionaries, with grog shops and churches, brothels and hotels. That was fully two decades before the Gold Rush led to the growth of San Francisco. In fact, Lahaina had America’s first high school west of the Mississippi. Since then, entire industries, such as pineapple cultivation, have come and gone, vanishing almost entirely. Great forests of koa and sandalwood were pillaged for export. Where fields of sugar cane flourished until quite recently, there are now virtual ghost towns and abandoned mills.

Also surprising is how rapidly Hawaii changed after Captain Cook arrived in 1778. By the 1820s, Lahaina was a bustling center for whalers and missionaries, with grog shops and churches, brothels and hotels. That was fully two decades before the Gold Rush led to the growth of San Francisco. In fact, Lahaina had America’s first high school west of the Mississippi. Since then, entire industries, such as pineapple cultivation, have come and gone, vanishing almost entirely. Great forests of koa and sandalwood were pillaged for export. Where fields of sugar cane flourished until quite recently, there are now virtual ghost towns and abandoned mills. Then, we join a cruise that starts at the Big Island and ends on Maui. Carrying around 30 passengers, the

Then, we join a cruise that starts at the Big Island and ends on Maui. Carrying around 30 passengers, the  Other evenings, special guests come on board. A hula troupe gives a performance that is nothing like what tourists experience at most resorts and commercial luaus. The lead dancers are men. They do aggressive, warlike steps, much like the Maori haka in New Zealand, rather than gentle, flowing ones. The moves are accompanied by chanting and drumming. There is not a ukelele or guitar in sight. We join them in drinking awa, a mildly narcotic ceremonial potion known elsewhere in the Pacific as kava. Another night, we meet Lawrence Aki, a hulk of a man who exudes quiet dignity, and his young disciple Kawika. Lawrence is a kumu (teacher) from a remote valley on Molokai. Kawika has lived with him for five years, helping at first in the taro patch and learning the old ways. This includes speaking the Hawaiian language and reciting genealogies. “It’s a lifetime commitment,” Lawrence says.

Other evenings, special guests come on board. A hula troupe gives a performance that is nothing like what tourists experience at most resorts and commercial luaus. The lead dancers are men. They do aggressive, warlike steps, much like the Maori haka in New Zealand, rather than gentle, flowing ones. The moves are accompanied by chanting and drumming. There is not a ukelele or guitar in sight. We join them in drinking awa, a mildly narcotic ceremonial potion known elsewhere in the Pacific as kava. Another night, we meet Lawrence Aki, a hulk of a man who exudes quiet dignity, and his young disciple Kawika. Lawrence is a kumu (teacher) from a remote valley on Molokai. Kawika has lived with him for five years, helping at first in the taro patch and learning the old ways. This includes speaking the Hawaiian language and reciting genealogies. “It’s a lifetime commitment,” Lawrence says. The final morning, a humpback leaps in the distance. It is a fitting sendoff. We have an entire afternoon to enjoy before a midnight flight home, and we have decided to visit a small museum about Pacific whaling. It features the old tools and equipment and the many products produced from an estimated 292,000 great cetaceans killed by the American fleet alone between 1825 and 1872. Fortunately, the humpbacks have made a remarkable recovery in recent years, from a low of around 1,000 in the 1960s to 20,000 or more today. On display outside is the impressive skeleton of a 40-foot sperm whale.

The final morning, a humpback leaps in the distance. It is a fitting sendoff. We have an entire afternoon to enjoy before a midnight flight home, and we have decided to visit a small museum about Pacific whaling. It features the old tools and equipment and the many products produced from an estimated 292,000 great cetaceans killed by the American fleet alone between 1825 and 1872. Fortunately, the humpbacks have made a remarkable recovery in recent years, from a low of around 1,000 in the 1960s to 20,000 or more today. On display outside is the impressive skeleton of a 40-foot sperm whale.

In 1790, near Tahiti Island in the South Pacific, English sailors staged a mutiny on the board the ship ‘HMS Bounty’. Nine English mutineers, their Polynesian ‘wives’ and a few Tahitian men and women took the Bounty on a desperate search for a safe hideout. They found it on Pitcairn Island. After being settled by mutineers, the island’s early history was bloody, with many feuds and violent deaths. Now Pitcairn Island is peaceful and its fifty families, many of them descendants of that infamous Bounty crew, welcome visitors to their idyllic tropical home.

In 1790, near Tahiti Island in the South Pacific, English sailors staged a mutiny on the board the ship ‘HMS Bounty’. Nine English mutineers, their Polynesian ‘wives’ and a few Tahitian men and women took the Bounty on a desperate search for a safe hideout. They found it on Pitcairn Island. After being settled by mutineers, the island’s early history was bloody, with many feuds and violent deaths. Now Pitcairn Island is peaceful and its fifty families, many of them descendants of that infamous Bounty crew, welcome visitors to their idyllic tropical home.

Many Kona coffee brands are sold in Hawaii. Most of these are blends however. Those wishing to enjoy 100% Kona coffee should read the labels carefully to eliminate the blends. Compare the taste of 100% Kona coffee to the blend just once and you’ll understand why there is simply no comparison between the two.

Many Kona coffee brands are sold in Hawaii. Most of these are blends however. Those wishing to enjoy 100% Kona coffee should read the labels carefully to eliminate the blends. Compare the taste of 100% Kona coffee to the blend just once and you’ll understand why there is simply no comparison between the two. After the tour, visitors are invited to sample light and dark roasted versions of both premium grades known as Extra Fancy and Peaberry. Peaberry beans are an anomaly in that they are plump, single oval beans. Regular coffee beans have two halves with matching flat sides. While this difference seems insignificant, the impact on taste is profound. Peaberry beans have a milder, fruitier taste combined with lower caffeine and higher oil content than regular coffee. I enjoyed the Peaberry so much that I purchased a one pound bag of the lightly roasted beans. The taste was fruity and full-bodied.

After the tour, visitors are invited to sample light and dark roasted versions of both premium grades known as Extra Fancy and Peaberry. Peaberry beans are an anomaly in that they are plump, single oval beans. Regular coffee beans have two halves with matching flat sides. While this difference seems insignificant, the impact on taste is profound. Peaberry beans have a milder, fruitier taste combined with lower caffeine and higher oil content than regular coffee. I enjoyed the Peaberry so much that I purchased a one pound bag of the lightly roasted beans. The taste was fruity and full-bodied. The Ueshima Coffee Company offers a personalized hands-on roasting tour. Visitors can process their own half-pound bag of coffee beans and then apply a customized label to the product. Those not touring may sample the different Ueshima coffees in the company store.

The Ueshima Coffee Company offers a personalized hands-on roasting tour. Visitors can process their own half-pound bag of coffee beans and then apply a customized label to the product. Those not touring may sample the different Ueshima coffees in the company store.

The nearby Kona Historical Society’s Kona Coffee Living History Farm provides an unusual tour through an early 20th century coffee farm, owned and operated by a traditional Japanese family. A male guide outlines the early farming methods and equipment employed to cultivate and harvest coffee beans. Later, visitors are taken through the farm house by a kimono-clad female tour guide. Here they gain insight into how this family made use of its limited resources. Coffee farming was not a lucrative endeavor so the family was forced to make clothing from used coffee bean sacks. After touring the farm house, take some time to taste some different coffee types.

The nearby Kona Historical Society’s Kona Coffee Living History Farm provides an unusual tour through an early 20th century coffee farm, owned and operated by a traditional Japanese family. A male guide outlines the early farming methods and equipment employed to cultivate and harvest coffee beans. Later, visitors are taken through the farm house by a kimono-clad female tour guide. Here they gain insight into how this family made use of its limited resources. Coffee farming was not a lucrative endeavor so the family was forced to make clothing from used coffee bean sacks. After touring the farm house, take some time to taste some different coffee types. Those wishing to explore the finer points of coffee tasting would benefit by reviewing the steps in detail at

Those wishing to explore the finer points of coffee tasting would benefit by reviewing the steps in detail at

The journey had started four days earlier, in the Middle Sepik village of Pagwi, one of just two points on the river that can be reached by road. The Sepik River snakes its way through the northwest of PNG across 1126 kilometers. Like its formidable brethren the Amazon and the Congo, it is shrouded in myth, and holds incredible spiritual and artistic significance to its inhabitants. One local legend says that the river’s age and strength are so great that no stone can be found within 50 kilometers of its banks.

The journey had started four days earlier, in the Middle Sepik village of Pagwi, one of just two points on the river that can be reached by road. The Sepik River snakes its way through the northwest of PNG across 1126 kilometers. Like its formidable brethren the Amazon and the Congo, it is shrouded in myth, and holds incredible spiritual and artistic significance to its inhabitants. One local legend says that the river’s age and strength are so great that no stone can be found within 50 kilometers of its banks. The Haus Tambaran we visited was an impressive hut, built on stilts, but enclosed almost to the ground. Taking off our hats and leaving our bags, we entered to find groups of men seated around smoldering fires. Choking in the smoke as we climbed the wooden ladder to the next level, we were greeted by more men and high ceilings decorated with hundreds of carefully carved artifacts.

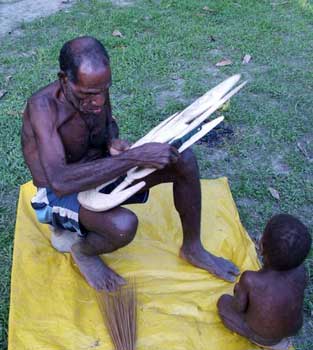

The Haus Tambaran we visited was an impressive hut, built on stilts, but enclosed almost to the ground. Taking off our hats and leaving our bags, we entered to find groups of men seated around smoldering fires. Choking in the smoke as we climbed the wooden ladder to the next level, we were greeted by more men and high ceilings decorated with hundreds of carefully carved artifacts. That night we stayed in a neighbouring village, about 30 minutes by canoe from Palembei. Sticky from the day’s heat, we jumped into the cloudy brown water of the Sepik and did our best to avoid thinking about what might be lurking in the water with us. Toes and fingers still intact, we shared a meal of rice and barramundi with the Chief of the village. Once the sun disappeared, so did the villagers, and within hours the songs of the river and rain forest had engulfed us and the flimsy bark floorboards we slept on.

That night we stayed in a neighbouring village, about 30 minutes by canoe from Palembei. Sticky from the day’s heat, we jumped into the cloudy brown water of the Sepik and did our best to avoid thinking about what might be lurking in the water with us. Toes and fingers still intact, we shared a meal of rice and barramundi with the Chief of the village. Once the sun disappeared, so did the villagers, and within hours the songs of the river and rain forest had engulfed us and the flimsy bark floorboards we slept on. Of course, PNG is not known as the land of the unexpected for nothing, and it wasn’t long before our careful plans drifted downstream. On our second day, we entered the Wasui Lagoon, a spectacular section of the Upper Sepik. As we traveled across the water, a group of black clouds grew across the sky. We were moving slowly and it was still several hours until dusk, when we would reach our hosts for the night. Nervous about the coming storm, our guides began tightening the ropes on the tarps while we prepared our ponchos. But once the rain started it was clear we didn’t stand a chance – each raindrop was a fistful splash of water. It seemed we had no choice but to stop at the nearest village.

Of course, PNG is not known as the land of the unexpected for nothing, and it wasn’t long before our careful plans drifted downstream. On our second day, we entered the Wasui Lagoon, a spectacular section of the Upper Sepik. As we traveled across the water, a group of black clouds grew across the sky. We were moving slowly and it was still several hours until dusk, when we would reach our hosts for the night. Nervous about the coming storm, our guides began tightening the ropes on the tarps while we prepared our ponchos. But once the rain started it was clear we didn’t stand a chance – each raindrop was a fistful splash of water. It seemed we had no choice but to stop at the nearest village.