by W. Ruth Kozak

So through me, freedom and the sea

will make their answer to the shuttered heart.”

– Pablo Neruda, The Poet’s Obligation.

I learned about the poet, Pablo Neruda, from a Chilean friend who brought me books of Neruda’s poetry. I didn’t dream that one day I would visit Neruda’s houses in Chile. My friend, exiled from his homeland after the military junta, always longed to return to his homeland but unfortunately passed away from cancer. So it was I who would go to Chile to explore the poet’s familiar haunts.

I learned about the poet, Pablo Neruda, from a Chilean friend who brought me books of Neruda’s poetry. I didn’t dream that one day I would visit Neruda’s houses in Chile. My friend, exiled from his homeland after the military junta, always longed to return to his homeland but unfortunately passed away from cancer. So it was I who would go to Chile to explore the poet’s familiar haunts.

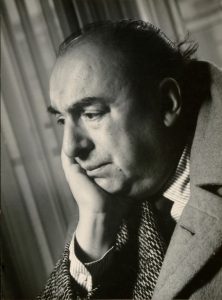

Born in 1904 in Parral, Chile, Neruda’s real name was Neflato Ricardo Reyes Basoalto. He published his first poem at the age of thirteen and by the time he was in his early twenties was a regular contributor to the literary journal “Selva Astral” under the pen-name of Pablo Neruda. He chose the name “Neruda” in memory of a Czechoslovak poet, Jan Neruda.

Pablo Neruda won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1971. His poetry is the soul of Chile and he played an important role in Chile’s recent history as a political icon and one of Chile’s national heroes. His picture appears everywhere alongside that of the late president, Salvadore Allende and the renown folk singer, Victor Jara who were brutally murdered by the military during the 1974 junta.

When I arrived in Chile, my first stop was Santiago. It’s an impressive city. The grand colonial architecture of the Plaza de Armes is a contrast to the ultra modern high-rises of Barrio Las Condes, Santiago’s financial district. A sleek modern metro system makes it easy to get around. My first stop would be Barrio Bellavista, where Neruda’s house, La Chascona, is located in the bohemian district.

A walk through Barrio Bellavista is pleasant, with craft shops and sidewalk cafes where the young folk from the local university congregate. It’s a community of artists, writers and craftsmen. The streets are shaded by trees and there are interesting shops and buildings. I found an artisan’s market and jewelry shops full of lapis lazuli. (Chile has major deposits of this semi precious gem.) The sidewalk cafes are lively with the chatter of students from the nearby university.

La Chascona

It wasn’t difficult to find the poet’s house, La Chascona, on a little back street set on a hillside overlooking the city. “La Chascona” means “wild hair” and the house is named after Matilde, his third wife, who had a tumble of unruly tresses.

It wasn’t difficult to find the poet’s house, La Chascona, on a little back street set on a hillside overlooking the city. “La Chascona” means “wild hair” and the house is named after Matilde, his third wife, who had a tumble of unruly tresses.

When he was young, Neruda was awarded a diplomatic post and his subsequent travels brought him international fame. Despite his Leftist beliefs, he had a flamboyant life and was friends with artists such as Pablo Picasso and Diego Rivera whose painting hang in his houses. As a diplomat and ambassador for Chile, Neruda travelled to many countries. He collected mementos of all his journeys and these souvenirs, everything from ash trays to primitive carved masks from the South Pacific and Africa, decorate the rooms.

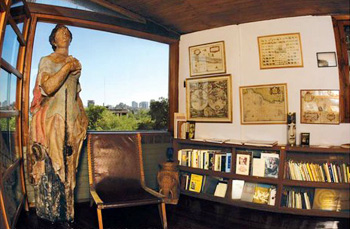

Neruda was fascinated by the sea, although he didn’t like to sail on it, and each of his houses are built in a ship motif. He even wrote his poetry in blue and green ink, sea colors. Some of his hand written poems are on display as well as his books. My favorite collection is Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, and what a thrill to see the original publication of it in Neruda’s library collection!

Until the military coup, La Chascona used to be crammed with Neruda’s treasures. The military ransacked the house and partially burned it. Restorations have been made, but many of his precious collections were destroyed. What is left is an amazing assortment of curios and whimsical items. The house has tiny rooms, so only a few people at a time are allowed in with a guide who explains everything in a most enjoyable and informative way, telling little anecdotes about the poet who was a fun loving and whimsical guy just as he was a serious political and literary figure. The Neruda Foundation maintains the house and has its headquarters there.

La Sebastiana

On the coast at Valparaiso, the second of Neruda’s houses, La Sebastiana, is set high on one of Valparaiso’s many steep hills commanding a view of the harbor. I took an ascendor from Espirito Santo up Cerro Bellavista where the house is located. I wended my way through the maze of narrow lanes, past a colorful hodge-podge of houses and eventually found the poet’s house.

On the coast at Valparaiso, the second of Neruda’s houses, La Sebastiana, is set high on one of Valparaiso’s many steep hills commanding a view of the harbor. I took an ascendor from Espirito Santo up Cerro Bellavista where the house is located. I wended my way through the maze of narrow lanes, past a colorful hodge-podge of houses and eventually found the poet’s house.

Neruda didn’t spend as much at La Sebastiana as he did at his other two houses, but he always went there for New Years to watch the annual fireworks from his lookout. The house, which was built by an Italian carpenter named Sebastian (for whom it was named) was, Neruda said, ‘a poet with wood’. Like the other houses it follows his style of the eccentric layout and the ship motif. The first floor was owned and occupied by two of Neruda’s friends and the ceiling murals and beautiful stone mosaics were done by the woman, who was an artist. In the lobby are two paintings by Neruda’s second wife, who was an artist twenty years his senior.

Neruda’s living quarters were on the second floor, ascending several floors up to the top room which was his study and lookout, with a broad spectacular view of Valparaiso’s harbor and the ocean. Each room in the house is full of the usual trinkets and beautiful knick-knacks he loved to collect. There are some lovely stained glass windows. You are allowed to wander around at will. Visitors are given booklets to read describing the history of each room and the furnishing and objects although no photographs are allowed other than the many breathtaking vistas from the windows.

Neruda’s living quarters were on the second floor, ascending several floors up to the top room which was his study and lookout, with a broad spectacular view of Valparaiso’s harbor and the ocean. Each room in the house is full of the usual trinkets and beautiful knick-knacks he loved to collect. There are some lovely stained glass windows. You are allowed to wander around at will. Visitors are given booklets to read describing the history of each room and the furnishing and objects although no photographs are allowed other than the many breathtaking vistas from the windows.

One of my biggest thrills was to stand at Neruda’s desk and look around at what he could see from there while he was writing. As in each of his houses there was a magnificent view. And surrounding him were all the objects he loved, including his books and manuscripts. I stood in the poet’s study as I did in each of his homes, and looked around at what he would see as he sat at the desk to write — the panoramic view of the sea from the window, the shelves of books, the pictures of Walt Whitman he had in each of his studies, his personal treasures, and on the desk a manuscript, as always written in green or blue ink, the colors of the sea.

Isla Negra

I took a bus down the coast to Neruda’s house at Isla Negra, which isn’t really an island. The house is built on a rocky headland overlooking the Pacific close enough to the shore to give that effect. The original stone buildings were erected in the late ‘30’s and were completed in the 1950’s. Neruda added to it bit by bit including various rooms to hold all his eccentric collections.

I took a bus down the coast to Neruda’s house at Isla Negra, which isn’t really an island. The house is built on a rocky headland overlooking the Pacific close enough to the shore to give that effect. The original stone buildings were erected in the late ‘30’s and were completed in the 1950’s. Neruda added to it bit by bit including various rooms to hold all his eccentric collections.

The house is built to resemble a ship, even to the low doorways. Being so near the crashing waves of the ocean, it has a realistic effect. Neruda’s impressive collection of ship’s figureheads decorate nearly every room. As well, there are masks and other wooden carvings from various places in the world. An entire room is devoted to his massive shell collection, even the tusk of a narwhal which he brought from Norway. I was most impressed by the bedroom which has windows facing the sea, the bed at an angle so the ocean can be clearly viewed.

During the junta, when Neruda was dying of cancer, the military stormed the house, but it has been mainly preserved just as it was, intact with his marvelous collections (even more fantastical than those at La Chascona). It is exactly as it was when Neruda and Matilde lived there, even to the place settings at the dining room table: place mats of sailing ships and one (the captain’s) of nautical instruments.

During the junta, when Neruda was dying of cancer, the military stormed the house, but it has been mainly preserved just as it was, intact with his marvelous collections (even more fantastical than those at La Chascona). It is exactly as it was when Neruda and Matilde lived there, even to the place settings at the dining room table: place mats of sailing ships and one (the captain’s) of nautical instruments.

“I am the captain and the guests are my crew,” he would say. In the middle of the table is a large crystal brandy snifter still containing brandy, because Neruda lost the key to open it.

As in the other houses, there’s a well-stocked bar where Neruda played the role of bartender. I can almost imagine him standing there, pouring drinks as he engaged in jolly banter with his guests. And outside, beached on the shore, is a small boat where he would also entertain. (The boat never went into the water!)

As in the other houses, there’s a well-stocked bar where Neruda played the role of bartender. I can almost imagine him standing there, pouring drinks as he engaged in jolly banter with his guests. And outside, beached on the shore, is a small boat where he would also entertain. (The boat never went into the water!)

Neruda is buried at Isla Negra, alongside his third wife, Matilda who died some years later. Their grave faces the ocean, on a round stone platform, surrounded by a bed of flowers. His will left everything to the Chilean people through the Neruda Foundation which is in charge of his properties. Neruda had returned to Chile when Allende was elected and twelve days after Allende was killed in the bombing of the Presidential Palace, he died of cancer. Some say he died of a broken heart.

As I stood by Neruda’s graveside and looked out over the blue Pacific, I thanked the Chilean friend who had introduced me to the poet, and thought of Neruda’s words in his poignant poem, “A Song of Despair”:

The memory of you emerges from the night around me.

The river mingles its stubborn lament with the sea

Deserted like the wharves at dawn

It is the hour of departure, oh deserted one!”

If You Go:

About the Poet

♦ Pablo Neruda’s bio

The Houses

♦ La Chascona

♦ La Sebastiana

♦ Isla Negra

The Pablo Neruda Trail and Chilean Wine

About the author:

Ruth Kozak writes poetry and has been inspired by Neruda. She is also a traveler and appreciated this opportunity to visit the poet’s houses. You can read some of her published travel stories etc. on her website www.ruthkozak.com

Photo credits:

Pablo Neruda by Annemarie Heinrich, 1967 by Annemarie Heinrich (1912-2005) / Public domain

Salvador Allende y Pablo Neruda by Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional / CC BY 3.0 CL

All other photos by W. Ruth Kozak

Spanish Uruguay has two locations– one in Montevideo and one in Atlantida. Since I was no longer interested in the nonstop action that characterizes the city life, I chose the enchanting coastal town of Atlantida. Pablo, the son of the lead professor, sent me photos of two living locations. One was a high rise near the beach, the other was a small, enchanting apartment complex called Isla Negra.

Spanish Uruguay has two locations– one in Montevideo and one in Atlantida. Since I was no longer interested in the nonstop action that characterizes the city life, I chose the enchanting coastal town of Atlantida. Pablo, the son of the lead professor, sent me photos of two living locations. One was a high rise near the beach, the other was a small, enchanting apartment complex called Isla Negra. Isla Negra was one of the many one of the many houses belonging to Pablo Neruda, a romantic poet who writer Gabriel García Márquez referred to as “the greatest 20th century poet in any language.” His passion for politics equaled his capacity for love.

Isla Negra was one of the many one of the many houses belonging to Pablo Neruda, a romantic poet who writer Gabriel García Márquez referred to as “the greatest 20th century poet in any language.” His passion for politics equaled his capacity for love.

In her book titled

In her book titled  The gardener was a good friend of Neruda’s driver, Manuel Araya, who was the only person who knew about Pablo’s dalliances. In her book, Matilde states her suspicion that the driver gave the gardener some ammunition by telling him about Pablo’s mistress, which if course, got back to Delia. Pablo and Delia divorced, and Matilde and Pablo eventually became husband and wife.

The gardener was a good friend of Neruda’s driver, Manuel Araya, who was the only person who knew about Pablo’s dalliances. In her book, Matilde states her suspicion that the driver gave the gardener some ammunition by telling him about Pablo’s mistress, which if course, got back to Delia. Pablo and Delia divorced, and Matilde and Pablo eventually became husband and wife.

La Esmeralda, a stately four-masted barquentine, pride of the Chilean Navy, was built in Cadiz, Spain in 1946 and was to become Spain’s national training ship. Due to several explosions at the shipyards, work was halted and eventually she was sold to Chile to help pay off debts incurred as a result of the Spanish Civil War. She was officially launched in 1953. Esmeralda is now a training ship for the Chilean Navy, visiting ports worldwide as a floating embassy for Chile.

La Esmeralda, a stately four-masted barquentine, pride of the Chilean Navy, was built in Cadiz, Spain in 1946 and was to become Spain’s national training ship. Due to several explosions at the shipyards, work was halted and eventually she was sold to Chile to help pay off debts incurred as a result of the Spanish Civil War. She was officially launched in 1953. Esmeralda is now a training ship for the Chilean Navy, visiting ports worldwide as a floating embassy for Chile. Unfortunately La Esmeralda’s reputation was sullied during the infamous Augusto Pinochet regime from 1973 to 1980 when she was used as a floating jail and torture chamber for political prisoners. The Chilean Navy was the advance guard of Augusto Pinochet’s coup and after the overthrow of Salvador Allende’s democratically elected socialist government, naval patrols scoured the streets of Valparaiso broadcasting the names of people demanding them to hand themselves in. Among them was an Anglo-Chilean priest, Father Michael Woodward. He was arrested at his home by a naval patrol and taken to the headquarters of the local Carabineros where he was brutally assaulted, then transferred to La Esmeralda where he was reputedly tortured and died. Doctors claimed he had died of a heart attack and the navy refused to give him a proper burial but dumped his body in a mass grave. Michael Woodward was one of the most prominent of those tortured on the ship. Several hundred other detainees, sympathizers of the ousted socialist president Allende, were taken there and suffered various fates including beatings, sexual assaults, electrocution and water torture. Consequently these days when she sails into port, crowds of protestors – political groups and Chilean exiles –gather demanding retribution in the form of a formal apology from the Chilean government and request that a plaque in the shape of a dove be put on the ship bearing the names of the victims. To date, these requests have been refused.

Unfortunately La Esmeralda’s reputation was sullied during the infamous Augusto Pinochet regime from 1973 to 1980 when she was used as a floating jail and torture chamber for political prisoners. The Chilean Navy was the advance guard of Augusto Pinochet’s coup and after the overthrow of Salvador Allende’s democratically elected socialist government, naval patrols scoured the streets of Valparaiso broadcasting the names of people demanding them to hand themselves in. Among them was an Anglo-Chilean priest, Father Michael Woodward. He was arrested at his home by a naval patrol and taken to the headquarters of the local Carabineros where he was brutally assaulted, then transferred to La Esmeralda where he was reputedly tortured and died. Doctors claimed he had died of a heart attack and the navy refused to give him a proper burial but dumped his body in a mass grave. Michael Woodward was one of the most prominent of those tortured on the ship. Several hundred other detainees, sympathizers of the ousted socialist president Allende, were taken there and suffered various fates including beatings, sexual assaults, electrocution and water torture. Consequently these days when she sails into port, crowds of protestors – political groups and Chilean exiles –gather demanding retribution in the form of a formal apology from the Chilean government and request that a plaque in the shape of a dove be put on the ship bearing the names of the victims. To date, these requests have been refused.

The ship itself truly is a beauty, a four-masted tall ship, one of the tallest and longest ships in the world. She has a crew of 300 sailors and 90 midshipmen, 46 of them women. Marcia, one of the lovely young female officers, took my friend and I around on a tour of the deck area, and explained the functions of the various pieces of equipment on board. The ship is spotless, the wooden decks polished and unmarred, the brass fittings shining in the afternoon sun. She pointed out the 21 sails and explained how every morning at 6 a.m. the trainees must climb to the top of the centre mast. If they falter or make a mistake they must do it again at noon. And if they make a bad error they must climb it again and again to get it right. She showed us the tasks she is responsible for every day as well as climbing up to secure the sails, although being a tall girl she only has to go part way up to do that. The shorter crew members are the ones who climb to the very top, a daunting job that not many people would have the courage to participate in.

The ship itself truly is a beauty, a four-masted tall ship, one of the tallest and longest ships in the world. She has a crew of 300 sailors and 90 midshipmen, 46 of them women. Marcia, one of the lovely young female officers, took my friend and I around on a tour of the deck area, and explained the functions of the various pieces of equipment on board. The ship is spotless, the wooden decks polished and unmarred, the brass fittings shining in the afternoon sun. She pointed out the 21 sails and explained how every morning at 6 a.m. the trainees must climb to the top of the centre mast. If they falter or make a mistake they must do it again at noon. And if they make a bad error they must climb it again and again to get it right. She showed us the tasks she is responsible for every day as well as climbing up to secure the sails, although being a tall girl she only has to go part way up to do that. The shorter crew members are the ones who climb to the very top, a daunting job that not many people would have the courage to participate in.

The town of Pisac (elevation about 9,500 ft) has a central market that is frequently visited by tour buses on their way to the ruins on the hills above Pisac. Most tours stop at the craft market and then head up to the ruins for the morning, and then move on down the Sacred Valley to other archaeological sites. From the town of Pisac, you can view the ancient Inca terraces far up on the steep hillsides. Looking up the steep slopes from Pisac, it is hard to imagine walking up the steep slopes of the mountains to labor making stone terraces and farm these remote and high fields, but evidently the Inca did it. In the ancient construction of the agricultural terraces included both normal stairs and stones inserted into the walls to allow them to move up through the terraces as they tended their crops on the high slopes.

The town of Pisac (elevation about 9,500 ft) has a central market that is frequently visited by tour buses on their way to the ruins on the hills above Pisac. Most tours stop at the craft market and then head up to the ruins for the morning, and then move on down the Sacred Valley to other archaeological sites. From the town of Pisac, you can view the ancient Inca terraces far up on the steep hillsides. Looking up the steep slopes from Pisac, it is hard to imagine walking up the steep slopes of the mountains to labor making stone terraces and farm these remote and high fields, but evidently the Inca did it. In the ancient construction of the agricultural terraces included both normal stairs and stones inserted into the walls to allow them to move up through the terraces as they tended their crops on the high slopes. The next morning after arriving in town, finding a place to stay and getting some food for the hike, we set out up the stairs leading from town to the first set of terraces. We headed through the market stalls selling colorful alpaca wool shawls, blankets and hats, stopping to barter and eventually buy some woolen hats to ward off the chill of the thin mountain air. Leaving the market by a small back street passing between mud wall compounds and heading towards the steep slopes at the edge of town, we walked over the cobblestones of a path which led up towards the first ascent into the terraces above the village.

The next morning after arriving in town, finding a place to stay and getting some food for the hike, we set out up the stairs leading from town to the first set of terraces. We headed through the market stalls selling colorful alpaca wool shawls, blankets and hats, stopping to barter and eventually buy some woolen hats to ward off the chill of the thin mountain air. Leaving the market by a small back street passing between mud wall compounds and heading towards the steep slopes at the edge of town, we walked over the cobblestones of a path which led up towards the first ascent into the terraces above the village.

Fortunately, we had been at high elevations for over a week to allow our bodies enough time to adjust to the elevation and thin mountain air, so the climb did not cause any altitude sickness. As we steadily climbed the hill, breathing heavily as we strained to extract oxygen from the cool and crisp morning air, we climbed a long series of stairs up between two small guard towers. We continued through the high farm terraces and into the ruins of small settlement on the steep slopes where the buildings had been laid out to form the shape of a bird when viewed from above. Then we climbed up to the ceremonial center of Intihuatana within the ruins.

Fortunately, we had been at high elevations for over a week to allow our bodies enough time to adjust to the elevation and thin mountain air, so the climb did not cause any altitude sickness. As we steadily climbed the hill, breathing heavily as we strained to extract oxygen from the cool and crisp morning air, we climbed a long series of stairs up between two small guard towers. We continued through the high farm terraces and into the ruins of small settlement on the steep slopes where the buildings had been laid out to form the shape of a bird when viewed from above. Then we climbed up to the ceremonial center of Intihuatana within the ruins. From the ceremonial center, we moved up through an Inca tunnel carved into the rocky mountain top, along a defensive wall beneath military barracks (where they guarded the main entrance) and into a saddle that had sacred baths and views of cliff sides with burial caves in them. Since the caves have been hit by grave robbers, tourists are not allowed into that area. We finished by going to the tour bus drop off area to get a some fresh squeezed orange juice before heading back down into town. In addition to the sense of accomplishment from having climbed all the way up (11,200 feet above see level) from town (over 1,700 feet of elevation gain) we got to visit the site in the opposite direction as the flow of the tour groups, and we could not help but feel a little smug as tourists huffed and puffed their way back to the bus parking area after their short tour, loudly complaining about the short hike.

From the ceremonial center, we moved up through an Inca tunnel carved into the rocky mountain top, along a defensive wall beneath military barracks (where they guarded the main entrance) and into a saddle that had sacred baths and views of cliff sides with burial caves in them. Since the caves have been hit by grave robbers, tourists are not allowed into that area. We finished by going to the tour bus drop off area to get a some fresh squeezed orange juice before heading back down into town. In addition to the sense of accomplishment from having climbed all the way up (11,200 feet above see level) from town (over 1,700 feet of elevation gain) we got to visit the site in the opposite direction as the flow of the tour groups, and we could not help but feel a little smug as tourists huffed and puffed their way back to the bus parking area after their short tour, loudly complaining about the short hike.

Old Tiwanaku covered at least 30 hectares; the vast majority of the site has yet to be excavated. The most outstanding structure, the Pyramid of Akapana, was constructed during the Classical Age of Tiwanaku Culture around 300 CE. At 18 meters high, this square structure consists of seven stacked platforms set over a natural hill. The present structure had to be partly reconstructed because the Spanish conquistador Oyardeburu’s demolition crew had haphazardly searched for treasure inside.

Old Tiwanaku covered at least 30 hectares; the vast majority of the site has yet to be excavated. The most outstanding structure, the Pyramid of Akapana, was constructed during the Classical Age of Tiwanaku Culture around 300 CE. At 18 meters high, this square structure consists of seven stacked platforms set over a natural hill. The present structure had to be partly reconstructed because the Spanish conquistador Oyardeburu’s demolition crew had haphazardly searched for treasure inside.

The Akapana Pyramid appears to have been multi-purpose. According to Miguel, the summit was an observatory. The astronomers worked within the bounds of a shallow, sunken, chamber open to the sky. This chamber was once shaped like an Andean Cross; a stepped-cross made up of an equal-armed cross indicating the cardinal points of the compass and a superimposed square. This cross symbolizes the three levels of heaven, earth and underworld. Needless to say, you require some imagination to see this figure. The summit holds the remains of a house whose rooms were used for preparing ritual ceremonies involving human sacrifice to the sun.

The Akapana Pyramid appears to have been multi-purpose. According to Miguel, the summit was an observatory. The astronomers worked within the bounds of a shallow, sunken, chamber open to the sky. This chamber was once shaped like an Andean Cross; a stepped-cross made up of an equal-armed cross indicating the cardinal points of the compass and a superimposed square. This cross symbolizes the three levels of heaven, earth and underworld. Needless to say, you require some imagination to see this figure. The summit holds the remains of a house whose rooms were used for preparing ritual ceremonies involving human sacrifice to the sun. Descend the pyramid and move toward the nearby Kalasasaya Temple platform. The walls of the platform include huge red sandstone and andesite blocks, some of which weigh as much as 100 tons. The nearest andesite quarries are located at Copacabana – 40 kilometers distant. The sandstone quarries were only 10 kilometers away. The massive blocks were transported to Tiwanaku using wooden boats.

Descend the pyramid and move toward the nearby Kalasasaya Temple platform. The walls of the platform include huge red sandstone and andesite blocks, some of which weigh as much as 100 tons. The nearest andesite quarries are located at Copacabana – 40 kilometers distant. The sandstone quarries were only 10 kilometers away. The massive blocks were transported to Tiwanaku using wooden boats. The mere eight-foot climb to the top of Tiwanaku’s most sacred temple also leaves you short-of-breath. At the top of the platform to your left is the National Symbol of Bolivia – the Gate of the Sun (Puerta del Sol). Weighting three tons, this gate is carved from a single slab of andesite. The crack in the lintel occurred when the gate was moved from its original location near the center of the platform.

The mere eight-foot climb to the top of Tiwanaku’s most sacred temple also leaves you short-of-breath. At the top of the platform to your left is the National Symbol of Bolivia – the Gate of the Sun (Puerta del Sol). Weighting three tons, this gate is carved from a single slab of andesite. The crack in the lintel occurred when the gate was moved from its original location near the center of the platform. Contrasting with the raised Kalasasaya Temple, the open- air Semisubterranean Temple is 2 meters below ground level. Descending a shallow set of stairs into the open-air room, you find yourself surrounded by 175 stone faces jutting out from the walls; they might be sizing you up as the next potential sacrifice. Each of these well-worn limestone faces is unique and might possibly represent the different tribes/peoples living within the empire of Tiwanku. At its zenith, the empire stretched from present-day northwest Argentina to northern Chile. On the other hand, Miguel did refer to one of the faces as “an alien”. Perhaps the empire is a little larger than originally believed.

Contrasting with the raised Kalasasaya Temple, the open- air Semisubterranean Temple is 2 meters below ground level. Descending a shallow set of stairs into the open-air room, you find yourself surrounded by 175 stone faces jutting out from the walls; they might be sizing you up as the next potential sacrifice. Each of these well-worn limestone faces is unique and might possibly represent the different tribes/peoples living within the empire of Tiwanku. At its zenith, the empire stretched from present-day northwest Argentina to northern Chile. On the other hand, Miguel did refer to one of the faces as “an alien”. Perhaps the empire is a little larger than originally believed. Next door, the Ceramic Museum outlines the Tiwanaku culture from its origins as a village circa 1580 BCE to the demise of the empire around 1200 CE, possibly the result of a prolonged drought and a receding Lake Titicaca.

Next door, the Ceramic Museum outlines the Tiwanaku culture from its origins as a village circa 1580 BCE to the demise of the empire around 1200 CE, possibly the result of a prolonged drought and a receding Lake Titicaca.