by Tom Koppel

Dozens of men are gathered on the muddy bank of the vast river, close to a precisely arranged pile of wood. With a shrouded corpse placed on top, this funeral pyre will soon be set on fire by a relative of the deceased. For Hindus, cremation on the shores of the holy Ganges assures the departed eternal salvation. A week-long trip along India’s sacred stream affords frequent glimpses of these ceremonial rites, along with ritual bathing, as the river boat glides past close by.

During our deluxe small-ship cruise, passengers gain a wealth of insights into the religious, historical and cultural world of the subcontinent’s largely rural and small-town heartland. Many of the encounters could never be had on a land-based group tour. It is the ideal way to experience the rich tapestry of life along the central artery of northern India.

During our deluxe small-ship cruise, passengers gain a wealth of insights into the religious, historical and cultural world of the subcontinent’s largely rural and small-town heartland. Many of the encounters could never be had on a land-based group tour. It is the ideal way to experience the rich tapestry of life along the central artery of northern India.

Arriving at Delhi, and following a day-trip to the Taj Mahal, my wife Annie and I fly on to Patna to begin our downstream Ganges journey. Sukapha (www.wlcvacations.com) is a 12-cabin, 40-metre, shallow-draught vessel built in 2006. Air-conditioned, spotlessly clean and well managed, its staff of over 20 pampers us from the first moments. Cabins have en suite bathrooms with showers and tasteful decor featuring rattan chairs and sofas and elegant hand-woven fabrics. There is a cheerful lounge for relaxing and enjoying a pre-dinner drink. The spacious, partially shaded, topside deck (with tea and cookies, or a cold beer, always available) is ideal for hours spent taking in the passing scenery.

The first evening, we meet our travelling companions: Brits, Aussies and fellow Canucks. We have always loved Indian food, and the chef pleases us with a delightful medley of Continental and Indian cuisine. There are various curries — lamb, chicken, fish and duck–all served with potatoes, rice, dahl (lentils) and an assortment of flat breads. The spiciness is slightly toned down for the Western palate. Delicious light desserts include orange soufflé, bread pudding and apple mousse. After dinner there is a briefing by Niv, our extremely knowledgeable guide, preparing us for the next day’s activities.

Each morning we are whisked away in comfortable SUVs on fascinating shore excursions to religious or historic sites and museums, or to stroll through villages and markets. The region has seen such a diversity of history that our outings amount to a virtual crash course in comparative religion and spiritual architecture.

At a major Sikh temple, we remove our shoes, cover our heads and join the congregation while an elder reads from the book of scriptures. Devotees bow, foreheads touching the floor, and leave offerings. Sikhs believe that nobody should go hungry. A communal kitchen is preparing breakfast for scores of local people. A cheerful team of women and men grill parathas to serve along with dal and chai (milky tea).

At a major Sikh temple, we remove our shoes, cover our heads and join the congregation while an elder reads from the book of scriptures. Devotees bow, foreheads touching the floor, and leave offerings. Sikhs believe that nobody should go hungry. A communal kitchen is preparing breakfast for scores of local people. A cheerful team of women and men grill parathas to serve along with dal and chai (milky tea).

A beautiful marble multi-domed Jain shrine, housing the ashes of a venerated holy man, is set in the middle of a lotus pond. In the inner sanctum, rice and nuts are scattered among decorative lamps. Jains practice non-violence towards all living beings, even avoiding stepping on insects. They follow a vegan diet and have the highest literacy rate and per capita income in India.

A young, bare-headed Jain woman in stylish contemporary clothing asks in impeccable English where we are from. She hands a friend her cell phone, eager to have her photo taken with a couple of visiting Canadians.

A young, bare-headed Jain woman in stylish contemporary clothing asks in impeccable English where we are from. She hands a friend her cell phone, eager to have her photo taken with a couple of visiting Canadians.

Most amazing are the geometrically precise red-brick ruins of two great ancient Buddhist universities, with meditation cells, lecture halls, and niches containing images of Lord Buddha. The larger, at Nalanda, once had 10,000 students and monks from all regions of Buddhist Asia. At the smaller, in Vikramshila, subjects included the tantric teachings of magic, such as flying and walking on water. Both were sacked in the late 12th century by Moslem invaders. Thousands of monks were beheaded or burned alive. The library at Nalanda held so many books that it burned for months. Today, the place is still revered. We watch as elegantly clad Buddhist monks from Thailand chant, pray and leave offerings of coloured cloth, blossoms and money at the large central temple.

Hindu temples and other sacred sites, old and modern, are everywhere. At one hot spring, people bathe or simply sprinkle holy water on their heads. We become familiar with the many incarnations of Vishnu and other deities, such as Ganesha, with the elephant head, and Hanuman, the monkey god. Our daily outings also offer unique opportunities to mingle with villagers, rub shoulders with cattle auctioneers and shop for local crafts.

Hindu temples and other sacred sites, old and modern, are everywhere. At one hot spring, people bathe or simply sprinkle holy water on their heads. We become familiar with the many incarnations of Vishnu and other deities, such as Ganesha, with the elephant head, and Hanuman, the monkey god. Our daily outings also offer unique opportunities to mingle with villagers, rub shoulders with cattle auctioneers and shop for local crafts.

Equally enriching, though, is simply observing the dramatic kaleidoscope of life on the river’s waters and nearby banks. Little wonder that the Ganges is regarded as a mother and goddess. She is alive and vibrant and ever-changing with the light and weather and seasons. We are there in mid-winter, a cool, dry season when the river is at extreme low water, exposing broad sandbanks that stretch to a distant horizon. During the summer monsoon, the water level is five to ten metres higher, flooding all the banks and low shorelines. Everything must look entirely different.

Winter low water enables a large population of nomadic peoples to eke out a riverside living in transient, seasonal encampments of thatched huts that have to be abandoned when the monsoon comes. We get to see this busy subsistence economy in its full and fascinating complexity.

Winter low water enables a large population of nomadic peoples to eke out a riverside living in transient, seasonal encampments of thatched huts that have to be abandoned when the monsoon comes. We get to see this busy subsistence economy in its full and fascinating complexity.

Tiny wooden fishing boats flit about, being sailed, paddled or poled upstream in the shallows, most with only one or two people on board. Individuals also wade in and cast simple nets. There are lots of rickety-looking but ingenious bamboo fishing structures set on poles just offshore, each with a large v-shaped net that is raised or lowered by shifting the weight of a single man. Catfish are a prized catch.

The monsoon renews the soil’s fertility each year. On low areas that flood in summer, we pass endless fields of winter rice and the telltale yellow of mustard, grown mainly for cooking oil. Large areas are covered in tall pampas grass and shorter swamp grass, which people harvest and pile up to dry, then bundle and sell for use as thatch and animal fodder.

Local passenger ferries crisscross the river from one crude landing spot to another, heavily laden with bicycles, goats, firewood and bundles of thatch. Adults wave as Sukapha sails by, and kids race along, shouting and trying to keep up. Where the bank is high enough, there are larger, flood-free permanent settlements. One Moslem village has an ornate mosque and a boatyard where dozens of large wooden vessels are pulled up for storage or repairs. Nearby, a game of cricket is being played.

Local passenger ferries crisscross the river from one crude landing spot to another, heavily laden with bicycles, goats, firewood and bundles of thatch. Adults wave as Sukapha sails by, and kids race along, shouting and trying to keep up. Where the bank is high enough, there are larger, flood-free permanent settlements. One Moslem village has an ornate mosque and a boatyard where dozens of large wooden vessels are pulled up for storage or repairs. Nearby, a game of cricket is being played.

The shallow, shifting navigable channel weaves here and there and is difficult to see in the murky water. Even with two professional pilots on board, we run aground abruptly several times. There are no permanent jetties, so we anchor each night in mid-channel.

One morning, we awake in such thick fog that nothing can be seen in any direction. It is impossible for our long, narrow “country boat,” used as a tender, to take us ashore for the planned excursion. Well, this is an adventure cruise after all, with all the uncertainty that entails.

When the fog lifts, there is an abundance of wildlife to see. Our sharp-eyed young naturalist, Babajan, positions himself on the sundeck with his binoculars, spotting and identifying birds and animals. Gangetic dolphins, which are blind, pop up frequently. Otters scurry across the sand bars. Herds of antelope roam the embankments along with countless cattle and goats. A few jackals lope past. The birds include herons, ospreys, ducks, geese, cormorants and storks. Every few minutes brings something new and memorable.

It is sad when the time comes to disembark at the 16-kilometre long Farakka Barrage, a dam where Sukapha enters a lock to begin a separate cruise down the Hugli River to Calcutta. But before heading home, we treat ourselves to three nights in Delhi at the Imperial, one of the world’s great classic hotels. Built in the 1930s in a mix of colonial and art deco styles, it embodies the essence of the old Raj. Truly an art museum, its halls and rooms display hundreds of fine paintings, sculptures, lithographs and photographs depicting British India of the early 20th century. We are there on Republic Day, a celebration of India’s Constitution, featuring a flag ceremony with pomp and elegant uniforms. Other traditions live on, such as High Tea (actually an elegant buffet meal) in the bright inner Atrium, where the diplomats of Delhi like to meet and greet. It is the perfect way to end our visit to India in style.

Sacred Varanasi and Ganges River Ceremony Tour

If You Go:

♦ Sukapha cruises the Ganges and Hugli rivers from July through April. Her sister ship Charaidew cruises the Brahmaputra river in Assam from October through April. For details, see: www.wlcvacations.com

♦ For Delhi’s grand Imperial hotel, see: www.theimperialindia.com

Private Sunrise Boat Ride on the River Ganges in Varanasi

About the author:

Tom Koppel’s latest book is Mystery Islands: Discovering the Ancient Pacific. It is available in Canada from Black Sheep Books, www.blacksheepbooks.ca, in the US at Amazon.com, or directly (signed and dedicated).

All photographs are by Annie Palovcik.

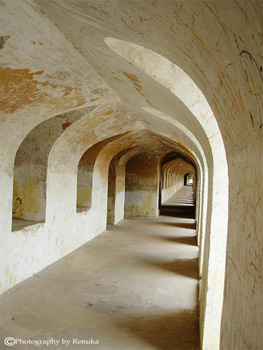

The mystery, the hidden truths and the mystic, all of it put together defines Lucknow’s Bada Imambada. Bhool Bhulayah (a part of the Imambada) is a fascinating labyrinth built by Asaf-ud-Daula (Nawab of Lucknow) in the 17th century. It’s located in the old area of Lucknow. To begin with, it’s one of the most underrated historical sites in the world!

The mystery, the hidden truths and the mystic, all of it put together defines Lucknow’s Bada Imambada. Bhool Bhulayah (a part of the Imambada) is a fascinating labyrinth built by Asaf-ud-Daula (Nawab of Lucknow) in the 17th century. It’s located in the old area of Lucknow. To begin with, it’s one of the most underrated historical sites in the world! It is not a regular monument with exquisite beauty to appreciate – it is way ahead of that. From its walls, windows to the rooftop, everything has a story and purpose. Nothing is ordinary. As the name suggests, it’s a labyrinth, where you may get lost! Yes, it is true. There are four sets of identical staircases in four different directions to confuse you; however, one of them leads you to the top of the Imambada. Unless you are with a guide, you cannot figure out the right way on your own!

It is not a regular monument with exquisite beauty to appreciate – it is way ahead of that. From its walls, windows to the rooftop, everything has a story and purpose. Nothing is ordinary. As the name suggests, it’s a labyrinth, where you may get lost! Yes, it is true. There are four sets of identical staircases in four different directions to confuse you; however, one of them leads you to the top of the Imambada. Unless you are with a guide, you cannot figure out the right way on your own!

While the flag drew attention thanks to its colourful nature, it was something else, which intrigued me – the presence of a smaller flag bearing the same colours above it.

While the flag drew attention thanks to its colourful nature, it was something else, which intrigued me – the presence of a smaller flag bearing the same colours above it. And so it remained for the next century and a half. In 1699, Raja Jai Singh II came to power at the death of his father. He was then just a 11 year old boy, but he came to be known as one of the most enlightened rulers of 18th century India. In addition to performing his duties as a warrior king, Raja Jai Singh also managed to find time to pursue his many interests, chief among which were mathematics and astronomy. He was regarded as a reputed astronomer, and he is most remembered for building the astronomical observatories known as ‘Jantar Mantars’. Above all, he was a farsighted ruler, who planned and built the beautiful city of Jaipur, which bears his name.

And so it remained for the next century and a half. In 1699, Raja Jai Singh II came to power at the death of his father. He was then just a 11 year old boy, but he came to be known as one of the most enlightened rulers of 18th century India. In addition to performing his duties as a warrior king, Raja Jai Singh also managed to find time to pursue his many interests, chief among which were mathematics and astronomy. He was regarded as a reputed astronomer, and he is most remembered for building the astronomical observatories known as ‘Jantar Mantars’. Above all, he was a farsighted ruler, who planned and built the beautiful city of Jaipur, which bears his name. At the time Jai Singh came to power, the Mughal ruler at the helm of the Indian Empire was Aurangzeb. The young king so impressed the Emperor that he was awarded the title ‘Sawai’. The word literally means ‘one and a quarter’, and the title meant that the king was a quarter above everyone else. Raja Jai Singh was the first to be awarded this title, and his descendents were allowed to use the same. It was then that the flag of the Kachwahas gained the additional flag – a quarter the size of the original flag, showing the same pattern and colours, it flew above the flag, proclaiming that it was the flag of the Sawai Maharajas – a quarter greater!!

At the time Jai Singh came to power, the Mughal ruler at the helm of the Indian Empire was Aurangzeb. The young king so impressed the Emperor that he was awarded the title ‘Sawai’. The word literally means ‘one and a quarter’, and the title meant that the king was a quarter above everyone else. Raja Jai Singh was the first to be awarded this title, and his descendents were allowed to use the same. It was then that the flag of the Kachwahas gained the additional flag – a quarter the size of the original flag, showing the same pattern and colours, it flew above the flag, proclaiming that it was the flag of the Sawai Maharajas – a quarter greater!!

After travelling for about two hours from Thiruvananthapuram, we reached the tip of India. It is a crowded little place with shops and hawkers selling shells of various shapes and sands of different colours. A small boat ride from the mainland took us to the famous Vivekananda rock, where the great philosopher had meditated. There are a lot books about his teachings which can be purchased. Next to this, stands the massive statue of Thiruvalluvar, the Tamil philosopher and poet also known as Valluvar, which has been constructed on another rock. These two are in fact the main tourist destinations in Kanyakumari. On the way to these rocks we saw many rocks protruding out of the sea. It could possibly have been a part of the mainland many ages ago.

After travelling for about two hours from Thiruvananthapuram, we reached the tip of India. It is a crowded little place with shops and hawkers selling shells of various shapes and sands of different colours. A small boat ride from the mainland took us to the famous Vivekananda rock, where the great philosopher had meditated. There are a lot books about his teachings which can be purchased. Next to this, stands the massive statue of Thiruvalluvar, the Tamil philosopher and poet also known as Valluvar, which has been constructed on another rock. These two are in fact the main tourist destinations in Kanyakumari. On the way to these rocks we saw many rocks protruding out of the sea. It could possibly have been a part of the mainland many ages ago. Another interesting attraction at Kanyakumari is the three different colours of the three bodies of water that you can see at one particular location. Shortage of time forced us to leave the same night back to Thiruvananthapuram and miss the next day’s beautiful sunrise. I would definitely like to come back to Kanyakumari some time soon and witness both the visual treats.

Another interesting attraction at Kanyakumari is the three different colours of the three bodies of water that you can see at one particular location. Shortage of time forced us to leave the same night back to Thiruvananthapuram and miss the next day’s beautiful sunrise. I would definitely like to come back to Kanyakumari some time soon and witness both the visual treats.

The well crafted boat sailed tranquilly on the gleaming lake and went past the little villages, the tiny canals, the alluring toddy shops and the green paddy fields. Due to the openness of the landscape, we were treated to a wonderful cooling breeze which made us sway like the coconut trees on the banks. After a round of games that included cards and charades, it was time for some bacardi blasts and a sumptuous lunch prepared by the in-house cooks. The fragrant whiff in the air said it all. The mouth watering seafood delicacies were spread out and within a flash it was time to lick the fingers.

The well crafted boat sailed tranquilly on the gleaming lake and went past the little villages, the tiny canals, the alluring toddy shops and the green paddy fields. Due to the openness of the landscape, we were treated to a wonderful cooling breeze which made us sway like the coconut trees on the banks. After a round of games that included cards and charades, it was time for some bacardi blasts and a sumptuous lunch prepared by the in-house cooks. The fragrant whiff in the air said it all. The mouth watering seafood delicacies were spread out and within a flash it was time to lick the fingers. A trip to the villages of Kerala must include a visit to the toddy shops. Toddy tastes best and fresh when you drink it in the morning as it turns sour as the day progresses. Nevertheless, we happily gulped it down. Nestled back inside the comforts of the kettuvellom, we watched at a few lanterns glowing in the distance from the many anchored boats and the houses besides the lake. It was a romantic sight.

A trip to the villages of Kerala must include a visit to the toddy shops. Toddy tastes best and fresh when you drink it in the morning as it turns sour as the day progresses. Nevertheless, we happily gulped it down. Nestled back inside the comforts of the kettuvellom, we watched at a few lanterns glowing in the distance from the many anchored boats and the houses besides the lake. It was a romantic sight.