London is a city that eats its history. If you peel back the layers of glass and steel in the Square Mile, you won’t just find Roman ruins and medieval crypts; you’ll find the remnants of a thousand years of appetites. This isn’t just a place where people trade stocks and dodge red buses. It’s a living, breathing pantry where every cobblestone has a story and every cellar once held something delicious-or dangerous. To truly understand the City of London, you have to follow your nose. From the salty tang of Roman oysters to the caffeinated buzz of the 17th-century coffee houses, the City’s timeline is written on its menus.

If you want to feel the weight of this history without actually becoming a museum exhibit yourself, you start at the heart of it all: the Bank of England. This area is the financial pulse of the world, but it’s also where some of the city’s most grand dining rooms reside. Take 1 Lombard Street, for example. Sitting right across from the Mansion House, this place is a former banking hall that screams “Old City” while whispering “New London.” Beneath its magnificent glass cupola, you can almost hear the ghosts of 19th-century clerks scratching their quills. It captures that essential City vibe-high ceilings, high stakes, and a sense that very important things are happening over very good eggs Benedict. It’s a fixture of the Square Mile’s landscape, a place where the grandeur of the past meets the frantic energy of the present.

Londinium: The Original Street Food Scene

Long before the bankers arrived, the Romans were the ones setting the table. When they founded Londinium around 47 AD, they brought more than just straight roads and bathhouses; they brought a taste for the finer things. Archaeological digs across the City-notably around Leadenhall Market-constantly turn up mountains of oyster shells. For the Romans, oysters weren’t a luxury served with a side of pretense; they were the original street food.

The Roman historian Tacitus described London as a “busy emporium for trade,” and food was the primary currency. You could walk through the forum and smell fermented fish sauce (garum), imported wine from Gaul, and spices that had traveled thousands of miles. The City was built on this trade. Even today, if you look at the street names around the Square Mile-Bread Street, Milk Street, Poultry-you’re looking at a medieval map of the City’s stomach. Each guild had its territory, and each territory had its flavor.

The Great Fire and the Rise of the Caffeine Cult

In 1666, the City effectively reset itself. The Great Fire tore through the timber-framed houses, leaving a charred skeleton in its wake. But like a sourdough starter that’s been fed and left to rise, the City came back stronger. Sir Christopher Wren didn’t just rebuild St. Paul’s Cathedral; he helped define the aesthetics of a new, stone-clad London.

Interestingly, the post-fire era wasn’t fueled by ale alone. This was the age of the coffee house. Places like Lloyd’s and Jonathan’s became the breeding grounds for the modern world. You didn’t just go for a brew; you went to hear the news, trade maritime insurance, or argue about politics. Samuel Pepys, the ultimate Londoner, famously recorded his first taste of “tee (a China drink)” in 1660. By the 1700s, there were more coffee houses in London than in any other city in the world besides Constantinople. They were “penny universities” where anyone with a coin could get an education in the latest gossip.

As the City grew wealthier, the food grew more ambitious. The “London Particular”-a thick pea and ham soup named after the yellow “pea-souper” fogs of the Victorian era-became a staple. It was heavy, comforting, and perfectly suited to a city that was increasingly industrial and soot-stained.

Narrative Dining: When Food Tells a Story

As we move into the middle of this century, London’s culinary identity has shifted again. We’ve moved past the era of bulk-feeding the masses and into an era of “narrative” dining. Today’s chefs aren’t just making dinner; they’re curators of memory.

You can see this shift in how restaurants across the capital-not just in the Square Mile-are obsessed with provenance and personal history. Even if you wander slightly west toward the refined streets of Belgravia, the influence of London’s storytelling tradition is everywhere. A key takeaway is that dining has become an autobiography. At Muse by Tom Aikens, for instance, the menu is literally built on the chef’s childhood memories. Every dish tells a story of a specific moment, a specific person, or a specific ingredient from his past. It’s a far cry from the anonymous “hot pies” cried out in the medieval streets. This trend of storytelling through plates has bled back into the City, where diners now expect to know the name of the farmer who grew their carrots and the exact coordinates where their scallops were dived.

Why do we care so much about the story? Perhaps it’s because, in a city that changes as fast as London, we crave connection. We want to feel that we aren’t just consuming calories, but participating in a legacy. Whether it’s a dish inspired by a Norfolk garden or a cocktail named after a long-lost London alleyway, the narrative is the seasoning.

Markets, Monasteries, and the Meat Trade

If you want to find the raw, visceral heart of the City’s food history, you have to head to Smithfield. This area has been a market for over 800 years. It was a place of “smooth fields” where livestock was traded, but it was also a place of public executions. The juxtaposition of the bloody meat trade and the somber shadow of the gallows is peak London.

The nearby Church of St. Bartholomew the Great, founded in 1123, is the oldest surviving church in London. Walking through its cloisters feels like stepping out of time. The monks here would have brewed their own beer and grown their own herbs, creating a quiet pocket of self-sufficiency amidst the chaos of the livestock market outside.

Today, Smithfield is the last of the great wholesale markets still operating in its historic home. It’s a place of early-morning white coats and the smell of fresh carcasses. But it’s also the site of a modern gastronomic renaissance. Tucked away right next to that ancient church is Restaurant St. Barts. It’s a Michelin-starred temple to British produce that feels utterly at home in this ancient corner of town. The dining room looks out over the cloisters, offering a view that hasn’t changed much in nine centuries. It’s a place where you can eat 15 courses of meticulously sourced British food while contemplating the “ongoing, epic churn of time,” as one critic famously put it. It captures the essence of Smithfield: ancient, unapologetic, and world-class.

The Future of the Square Mile

As we look toward the future of the City of London, it’s clear that the appetite for history isn’t fading. If anything, we’re becoming more obsessed with it. The new skyscrapers-the Cheesegrater, the Walkie-Talkie, the Scalpel-might look futuristic, but at their feet, people are still drinking in pubs that were rebuilt after the fire.

The City is currently undergoing a massive transformation into a “seven-day-a-week” destination. The bankers are still there, sure, but so are the tourists, the foodies, and the history buffs. We are seeing a return to the City as a social hub, much like the coffee houses of the 1700s. The streets are being reclaimed from cars and given back to people who want to walk, talk, and, most importantly, eat.

Notably, the rise of “Green Stars” and sustainable practices shows that London is finally learning to respect its resources as much as its traditions. We are moving toward a circular economy of food, where waste is minimized and localism is king. It’s a modern twist on the medieval guild system, where quality and provenance were the law of the land.

Conclusion

A travel guide to the City of London can never truly be finished because the City itself is never finished. It is a work in progress, a palimpsest where new menus are written over old ones. To visit the City is to join a long line of hungry people. Whether you’re standing in the shadow of the Roman Wall with a snack in hand or sitting in a high-backed chair under a Victorian dome, you are part of the feast.

The beauty of the Square Mile lies in its contrasts. It’s the sound of a high-tech kitchen humming next to a medieval graveyard. It’s the smell of roasted coffee beans in the same alleyway where merchants once traded silk. It’s the ability to find a world-class meal at Restaurant St. Barts just steps away from where ancient monks once sang their vespers.

So, don’t just look up at the skyscrapers. Look down at the pavement. Look through the windows of the basement bistros. Ask where the gin came from and why the soup is called what it’s called. London is a city that rewards the curious and the hungry. It’s a city that has survived fire, plague, and war, and through it all, it never forgot to set the table.

The Amaravati Stupa, also known as a Maha Chaitya or Great Stupa is considered to be the largest stupa in India, even larger than its most famous counterpart, the Sanchi Stupa. While the Sanchi Stupa is a major tourist attraction in India, the Amaravati Stupa suffered a different fate. Evidence has shown that the stupa built during the reign of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, remained a major religious site well into the 14th century when Hinduism had become the primary religion in India. Till about 1344 AD, various successive dynasties, helped in building and extending the stupa and its surrounding areas.

The Amaravati Stupa, also known as a Maha Chaitya or Great Stupa is considered to be the largest stupa in India, even larger than its most famous counterpart, the Sanchi Stupa. While the Sanchi Stupa is a major tourist attraction in India, the Amaravati Stupa suffered a different fate. Evidence has shown that the stupa built during the reign of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, remained a major religious site well into the 14th century when Hinduism had become the primary religion in India. Till about 1344 AD, various successive dynasties, helped in building and extending the stupa and its surrounding areas. The gallery also boasts of a sprawling collection of Hindu bronzes, statues and sculptures known almost misleadingly as the Bridge Collection. I admired the dark, seated stone figure of the Hindu sun god, Surya from 13th century Orissa, part of a group of eye catching sculptures which show the nine planets or the “navagrahas”. My eyes rested on a marvelously carved, seated stone figure of Ganesh, the remover of obstacles, also from the same era, depicted unusually with five heads and ten hands. The entire collection was amassed by Charles “Hindoo” Stuart, an Irish officer in the East India Company, known for his affinity to Hinduism and Indian culture. He collected antiquities mostly from the states of Bengal, Orissa, Bihar and Central India and displayed them at his home in Kolkata. After his death and burial in Kolkata in 1828, his impressive collection was transferred to England where it was sold in auction to John Bridge in 1829-30. Thus the collection was given to the museum in 1872 by the Bridge family heirs.

The gallery also boasts of a sprawling collection of Hindu bronzes, statues and sculptures known almost misleadingly as the Bridge Collection. I admired the dark, seated stone figure of the Hindu sun god, Surya from 13th century Orissa, part of a group of eye catching sculptures which show the nine planets or the “navagrahas”. My eyes rested on a marvelously carved, seated stone figure of Ganesh, the remover of obstacles, also from the same era, depicted unusually with five heads and ten hands. The entire collection was amassed by Charles “Hindoo” Stuart, an Irish officer in the East India Company, known for his affinity to Hinduism and Indian culture. He collected antiquities mostly from the states of Bengal, Orissa, Bihar and Central India and displayed them at his home in Kolkata. After his death and burial in Kolkata in 1828, his impressive collection was transferred to England where it was sold in auction to John Bridge in 1829-30. Thus the collection was given to the museum in 1872 by the Bridge family heirs.

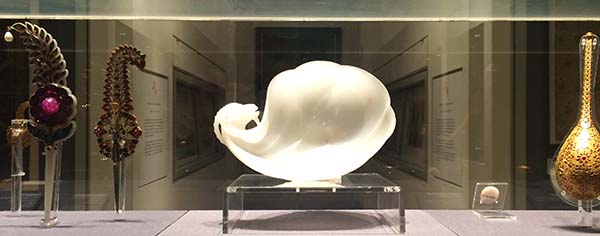

Following this, we walked over to see Tipu’s Tiger. Considered by the museum to be one of its most precious and popular objects, this intriguing musical tiger mauling a red coated European soldier was made for Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore, sometimes known as the “Tiger of Mysore” in South India. Tipu ruled from 1782 to 1799 and fought three wars against the British East India Company before being finally defeated and killed in his capital, Seringapatam in 1799. His treasury was immediately divided among the Company soldiers and the tiger was first displayed at the India museum in 1808. After the dissolution of the East India Company, this semi-automaton musical instrument was moved to the South Kensington museum, now the V & A and has been on display ever since. I realized that a visit to these two museums can be an enlightening as well as a poignant experience for most Indians.

Following this, we walked over to see Tipu’s Tiger. Considered by the museum to be one of its most precious and popular objects, this intriguing musical tiger mauling a red coated European soldier was made for Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore, sometimes known as the “Tiger of Mysore” in South India. Tipu ruled from 1782 to 1799 and fought three wars against the British East India Company before being finally defeated and killed in his capital, Seringapatam in 1799. His treasury was immediately divided among the Company soldiers and the tiger was first displayed at the India museum in 1808. After the dissolution of the East India Company, this semi-automaton musical instrument was moved to the South Kensington museum, now the V & A and has been on display ever since. I realized that a visit to these two museums can be an enlightening as well as a poignant experience for most Indians.

Garden of St. Michael’s Cornhill

Garden of St. Michael’s Cornhill