by Marsha Mildon

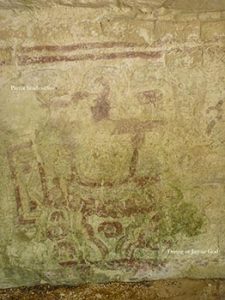

Standing alone, face to face with a mural depicting the Mayan diving god is one of those Indiana Jones moments that delight me when traveling. My first experience of this rare event happened in March of 2013 in the Xel Ha Architectural Zone. Now I admit up front that when wandering through pre-Hispanic cities in the Americas, I feel a real sense of communication with the original people. So I had been touring Mayan sites for years, but I had only seen murals in museums, never before on the original wall.

This first solo excursion resulted from seeing the small ruin on the beach at the Grand Sirenis resort in Xaac Bay. “That building looks like Tulum,” I thought.

This first solo excursion resulted from seeing the small ruin on the beach at the Grand Sirenis resort in Xaac Bay. “That building looks like Tulum,” I thought.

To check my memory, I returned to Tulum. Sure enough, the majority of buildings used a design like Xaac Bay: square, double rows of decorated stones around the top, and windows in the seaward side.

Some quick Internet research introduced me to the world of an extensive Mayan maritime trading network. From 900 AD to the Spanish conquest, trade was conducted in large Mayan canoes along the east coast from northern Yucatan as far south as Honduras.

As the large city states indulged in destructive wars, survivors moved to the coast and built, or adapted, simpler sites, in what is now called the East Coast Style, like Tulum. These sites had access to ocean fish and shellfish; were set on or near coastal harbors for their trading activities, and had one or more cenotes nearby for fresh water during a long drought.

Trade goods included everyday things such as salt for drying food and obsidian for knives, arrow points, tools, and weapons of war. Luxury items such as jade, turquoise, and quetzal feathers to show high rank were traded for the upper classes along with items like cotton and vanilla. And their trade currency was positively delightful: Cacao (chocolate) beans.

The map below is my rough sketch of the Yucatan Peninsula with several of the major Mayan trading centers marked. So far I have managed to visit El Rey, Ixchel, Xaman Ha, Xel Ha, Tancah, Tulum, and Muyil, viewing without meeting other tourists except for Tulum and Muyil. While there are interesting features for Maya-philes at all sties, my favorites are Xel Ha and Muyil.

Xel Ha

I chose Xel Ha for my first exploration. There was a driveway, a modern building where people took an entry fee, and a map on a sign. In I went.

I chose Xel Ha for my first exploration. There was a driveway, a modern building where people took an entry fee, and a map on a sign. In I went.

The Group I found first was Group B which showed typical East Coast style features: squared buildings, some with pillars, and evidence of the typical Maya practice of erecting new buildings over old. I was elated to be wandering through possible rooms of Mayan traders.

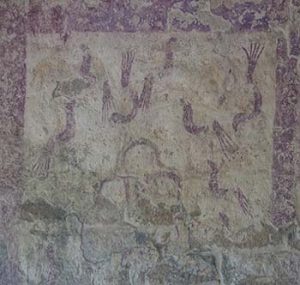

From Group B, I followed a path north toward buildings close to the highway, arriving at the Group of Birds. And there I saw my first mural on its original wall, the Bird Mural. The Temple of the Birds sits on several platforms so the murals are well above eye level, but easy to climb with care for building and one’s ankles. The Bird mural in red, green, and yellow shows a local long-tailed, short-beaked bird. It is an early Classic period around 300-600 AD when the site was first inhabited.

From Group B, I followed a path north toward buildings close to the highway, arriving at the Group of Birds. And there I saw my first mural on its original wall, the Bird Mural. The Temple of the Birds sits on several platforms so the murals are well above eye level, but easy to climb with care for building and one’s ankles. The Bird mural in red, green, and yellow shows a local long-tailed, short-beaked bird. It is an early Classic period around 300-600 AD when the site was first inhabited.

Following the building around to the south side, I found my personal favorite mural on the site, the three-panel mural with the diving god shown at the beginning of this article. The diving god — probably associated with the Mayan bees and Venus — stares down at the solo visitor from 1500 ago, an inspiring and somewhat solemn sight. This god was important to the Mayans, with murals and sculptures in many sites. Honey and astronomy, food and a world view —those were crucial to the ancient Mayans as their civilization struggled for survival, just as they are to us today.

From there, I walked east along the hot and sunny Sacbe, the Mayan white road built up with white rocks and shells, I arrived at the Jaguar Group and its beautiful — cooling— cenote.

From there, I walked east along the hot and sunny Sacbe, the Mayan white road built up with white rocks and shells, I arrived at the Jaguar Group and its beautiful — cooling— cenote.

After a quick dip, I examined the 3-columned palace of the Jaguar. Alas, the diving god mural that had been on the outer wall overlooking the cenote was severely damaged by Hurricane Wilma in 2005. However, peering in through a mesh barrier gave me a clear view of the large Jaguar mural in red ochre, black and the remarkable Mayan blue. Again, the black eyes of the Jaguar stared back at me, delivering their message from the Mayan culture. Those eyes look out from the milennium-old Mayan blue made of añil leaves traded from Guatemala and local clay, as brilliant as those at any larger site.

A small site, usually empty of other tourists, and now with good signage, Xel Ha is probably the best self-guided tour available to have a close-up encounter with ancient Mayans. It fairly glows with images of what was important to them.

Muyil or Chanyaché

Muyil or Chanyaché

To go to Muyil, on the other hand, I would choose one of the Mayan tour groups, both for the information their guides have and for the opportunity to enjoy a complete Mayan experience. Set in the Sian Ka’an United Nations Biosphere, the pyramids of Muyil rise out of jungle wetlands.

First settled around 300 BC, Muyil is one of the oldest continually inhabited trading sites, thus including classic pyramids similar to Tikal, round temples perhaps performance buildings or observatories, and the post classic East Coast building.

Unlike other trading centers, Muyil is not right at the ocean. Instead it is at the end of one natural canal, two freshwater lagoons, and a canal built by the Maya between 1000 and 2000 years ago. When I travelled there in 2016, nine of us took two boats through the first fresh water lagoon, the Mayan canal, the second lagoon and into the natural canal that flows to the sea.

Part way along this canal, there is a dock beside the boardwalk into the ruins. On my 2014 tour, we followed the boardwalk to the ruins. In 2016, we left our boat and floated down the canalsitting in life preservers. With a good current, because of the movement of fresh to salt water, this is a safe activity with lots of waterbirds around. And it’s fun; I laughed through the whole 40 minute float.

Back in the Mayan village, we had the option of choosing fish, Mayan style, (Tikin Xic),with a sauce made of gourd seeds, mild seasoning, tomatoes,onions, grilled in banana leaves by the villagers. My only regret is that I can’t find banana leaves for cooking it in Canada.

Combo Tour in Coba and Xel-Ha in Cancun

If You Go:

Xel Ha

In 2016, the Xel Ha Archeological Zone is now well signed so you can ask a collectivo driver or taxi driver to let you off near the entrance, on the east side of Hwy 307 about 300 yards south of the Xel Ha theme park. Cost is now 65 pesos. There is no food or water for sale and a lot of mosquitos, so bring your own snacks and some biodegradable insect repellent.

Muyil

It is possible to get to Muyil by car driving south of Tulum. However, this is a place that I prefer to visit with a local tour company, for both the information and the fun.

I have gone with both Community Tours Sian Kaan and Mayans Explorers and would recommend either. Both provide canal floats, boat rides, ruin tours as well as other activities. Whatever way you see Muyil, try to make sure it includes some genuine Mayan food. And take an extra T-shirt to wear while you float because even in hot weather, the water will cool you eventually.

Mayans Explorers is a family-owned tour company, with knowledgeable guides, many with appropriate PhDs. It has offices in Playa del Carmen but picks people up at their hotels.

Community Tours is a community organization started by Mayans from Sian Ka’an villages and hires local Mayans as guides, boat captains, bus drivers, cooks, and servers. It also gives monthly funds to the Mayan villages from the business. In addition to economic development they are also dedicated to environmental preservation. For these reasons, I personally choose them. They have offices in Tulum and also picks people up at hotels.

About the author:

The first time Marsh Mildon saw a photo of Machu Picchu was on her 40th birthday and her life changed. Since then, she has spent all my vacations and several months of volunteering in Central and South America, visiting ruins of many peoples and many ages. She is fascinated by the cultures of the ancient Americans. In between trips south, she works as a freelance writer/photographer with two published novels, several stage plays, and hundreds of non-fiction articles published (all in print not online).www.marshadelsol-mildon.artistwebsites.com.

All photos are by Marsha Mildon:

The jaguar temple

The Diving god at Xel Ha stares down at the visitor with its clear red ochre, green, and yellow colors.

Pillars, platforms, and new walls built over old are typical Mayan architectural styles that we can touch in Group B.

The bird mural is a three panel mural with images of birds on two sides with a somewhat indistinct Mayan symbol for ‘lord’ in the center.

The cenote can be seen from the Temple of the Jaguar and is lovely for a quick dip or foot paddle after walking the jungle-shrouded sacbe.

There are many good reasons to go to Cancún: a long, relaxing break from a stressful job, a way of visiting other cities in Quintana Roo and Yucatán like Tulúm or Mérida, a chance to

There are many good reasons to go to Cancún: a long, relaxing break from a stressful job, a way of visiting other cities in Quintana Roo and Yucatán like Tulúm or Mérida, a chance to

Curiously, this temple faces away from the other stone buildings at San Miguelito. Instead, it faces El Rey. Between the pyramid and El Rey, there may have been an uninterrupted stretch of houses and other structures. Unfortunately, “low level houses were not registered during the design and construction phase of the hotel zone during the seventies,” according to a National Institute of History and Anthropology (INAH) placard at San Miguelito.

Curiously, this temple faces away from the other stone buildings at San Miguelito. Instead, it faces El Rey. Between the pyramid and El Rey, there may have been an uninterrupted stretch of houses and other structures. Unfortunately, “low level houses were not registered during the design and construction phase of the hotel zone during the seventies,” according to a National Institute of History and Anthropology (INAH) placard at San Miguelito.

Most of these buildings as we see them date to the Postclassical era, but like most Maya structures, they were built in phases. The costa oriental temple had at least two construction phases. The pyramid at San Miguelito had at least three.

Most of these buildings as we see them date to the Postclassical era, but like most Maya structures, they were built in phases. The costa oriental temple had at least two construction phases. The pyramid at San Miguelito had at least three.

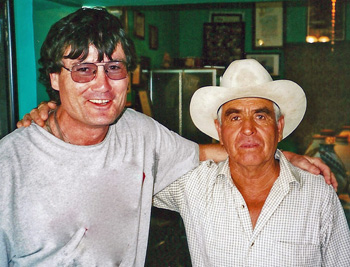

Quezada’s modest gallery is on the corner of the main street across from the historic, refurbished railroad line. As I enter, the artist, now in his early seventies, breezes in from the side room. Dressed in a faded tan cowboy hat, trim, medium height, bantamweight, looking fit as an Oklahoma rodeo wrangler, he welcomes me: “Buenas tardes, señor. Mi casa es su casa,” His rugged, suntanned face exudes a quiet humility and keen curiosity shaped by his many years of desert life. Later, he puts his arm around me, and Dick snaps my photo.

Quezada’s modest gallery is on the corner of the main street across from the historic, refurbished railroad line. As I enter, the artist, now in his early seventies, breezes in from the side room. Dressed in a faded tan cowboy hat, trim, medium height, bantamweight, looking fit as an Oklahoma rodeo wrangler, he welcomes me: “Buenas tardes, señor. Mi casa es su casa,” His rugged, suntanned face exudes a quiet humility and keen curiosity shaped by his many years of desert life. Later, he puts his arm around me, and Dick snaps my photo.

The pale sky-blue adobe walls in the front room are lined with ollas and vases, glazed in a rainbow of rust-red, brown, and eggshell hues and painted with intricate, geometric designs. Sunlight, streaming through the thin violet-blue curtains, casts an iridescent glow on them. I am mesmerized by their spiral, thin-walled shapes and meticulously painted and etched patterns.

The pale sky-blue adobe walls in the front room are lined with ollas and vases, glazed in a rainbow of rust-red, brown, and eggshell hues and painted with intricate, geometric designs. Sunlight, streaming through the thin violet-blue curtains, casts an iridescent glow on them. I am mesmerized by their spiral, thin-walled shapes and meticulously painted and etched patterns. My mind wanders as the room slowly fills with the lyrical beauty of Garcia’s baritone voice and guitar strumming. I gaze out the window. The heat glimmers over the parched, dust-colored land. Nothing seems to be alive except patches of creosote and agave clinging to the desert emptiness. How could such incredible artistic beauty come to exist in such a remote, hardscrabble place?

My mind wanders as the room slowly fills with the lyrical beauty of Garcia’s baritone voice and guitar strumming. I gaze out the window. The heat glimmers over the parched, dust-colored land. Nothing seems to be alive except patches of creosote and agave clinging to the desert emptiness. How could such incredible artistic beauty come to exist in such a remote, hardscrabble place? “The first time I saw those pieces,” Juan tells me in Spanish, “I knew I had found a hidden treasure. I knew that the ancient ones must have found the materials here.” Over many years, he has patiently experimented with different clays, pigments, drawing and firing techniques to make ollas or pots with the ancient culture’s iconography and design.

“The first time I saw those pieces,” Juan tells me in Spanish, “I knew I had found a hidden treasure. I knew that the ancient ones must have found the materials here.” Over many years, he has patiently experimented with different clays, pigments, drawing and firing techniques to make ollas or pots with the ancient culture’s iconography and design.

Like a tale out of the Wizard of Oz, it began in 1976 when MacCallum stopped off at a second-hand swap shop in the New Mexico border town of Deming where he bought three unsigned pots. Intrigued by their intricate beauty and wondering if they were pre-Columbian in origin, he embarked on an adventure south that would take him to Mata Ortiz and the unknown potter.

Like a tale out of the Wizard of Oz, it began in 1976 when MacCallum stopped off at a second-hand swap shop in the New Mexico border town of Deming where he bought three unsigned pots. Intrigued by their intricate beauty and wondering if they were pre-Columbian in origin, he embarked on an adventure south that would take him to Mata Ortiz and the unknown potter. The homes, some humble brick adobes; others larger cinder-block buildings, resonate with an infectious warmth and vitality for work. Children breeze in and out as if flying on broomsticks. Pots and vases line oilcloth-covered tables. I look over the shoulders of men and women as they shape, polish and paint at tiny sunlit work stations. They shape the lower portion of the object in a plaster mold, place a single coil of clay atop it, and then by hand work the clay upwards to form their thin-walled bowls, jars, and pots.

The homes, some humble brick adobes; others larger cinder-block buildings, resonate with an infectious warmth and vitality for work. Children breeze in and out as if flying on broomsticks. Pots and vases line oilcloth-covered tables. I look over the shoulders of men and women as they shape, polish and paint at tiny sunlit work stations. They shape the lower portion of the object in a plaster mold, place a single coil of clay atop it, and then by hand work the clay upwards to form their thin-walled bowls, jars, and pots. Today, one of Quezada’s pots can sell for thousands of dollars. In 1999, he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, Mexico’s highest award given to a living Mexican-born artist.

Today, one of Quezada’s pots can sell for thousands of dollars. In 1999, he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, Mexico’s highest award given to a living Mexican-born artist.

I had visited Ek Balam for the first time in 1995. I was on the way to Chichen Itza from Coba, on the old road. After passing the town of Valladolid, a dirt road led to this small site. It was called Ek Balam, Night Jaguar. I ended up there about midday when it was hot and humid, with no breeze at all. However, after driving all morning on a dirt road that seemed to be in the middle of nowhere and leading to nowhere, I spotted a small palapa hut. It was the ticket booth, and it looked deserted, just like everything else around us. When I stopped, an old Mayan man came out to the front of the hut. He was the caretaker of the site, or the ticket agent. I wished that I could speak Mayan, and his Spanish wasn’t much better than mine, so I felt like it was a missed opportunity to get to know someone interesting and to learn more about the place I was visiting from a local. I purchased my ticket from him and he pointed me in the right direction and I set off to see this little-known site.

I had visited Ek Balam for the first time in 1995. I was on the way to Chichen Itza from Coba, on the old road. After passing the town of Valladolid, a dirt road led to this small site. It was called Ek Balam, Night Jaguar. I ended up there about midday when it was hot and humid, with no breeze at all. However, after driving all morning on a dirt road that seemed to be in the middle of nowhere and leading to nowhere, I spotted a small palapa hut. It was the ticket booth, and it looked deserted, just like everything else around us. When I stopped, an old Mayan man came out to the front of the hut. He was the caretaker of the site, or the ticket agent. I wished that I could speak Mayan, and his Spanish wasn’t much better than mine, so I felt like it was a missed opportunity to get to know someone interesting and to learn more about the place I was visiting from a local. I purchased my ticket from him and he pointed me in the right direction and I set off to see this little-known site. I realized that the tallest pile of rubble, overgrown with trees, was a good sized pyramid. Although steep, with a barely visible trail on it, I climbed to its top. It was a real challenge for me since there were not even tall enough trees growing on it to shade me from the scorching sun. In spite of it, I still made it to the top and was rewarded with a great view. I could only guess how important this site would have been with a structure this big. I fantasized on seeing the pyramid and its features, wondering what they were like. I noticed big pieces of cut stones, that I recognized as part of a building. As I learned in later years, I had been standing on top of the Acropolis, indeed the biggest structure at the site.

I realized that the tallest pile of rubble, overgrown with trees, was a good sized pyramid. Although steep, with a barely visible trail on it, I climbed to its top. It was a real challenge for me since there were not even tall enough trees growing on it to shade me from the scorching sun. In spite of it, I still made it to the top and was rewarded with a great view. I could only guess how important this site would have been with a structure this big. I fantasized on seeing the pyramid and its features, wondering what they were like. I noticed big pieces of cut stones, that I recognized as part of a building. As I learned in later years, I had been standing on top of the Acropolis, indeed the biggest structure at the site. Years later, there I was standing on top of the same tall mound, but this time I had climbed it on a stairway, stopping along the way to marvel at the statues on its sides. The view from the top was pretty much the same though there were a lot more structures standing.

Years later, there I was standing on top of the same tall mound, but this time I had climbed it on a stairway, stopping along the way to marvel at the statues on its sides. The view from the top was pretty much the same though there were a lot more structures standing. Ek Balam is a very compact site. Although it was a larger city, only the center of it, the main plaza has been excavated, which covers about one square mile. This makes it very easy to walk, though. A large arch stands at the entrance of the city, with the remains of a sac-be going through it. The sac-be, or ancient Mayan road (translated as “white road”, due to the color of the limestone that it had been constructed from), connected Ek Balam to other sites, like Coba and Chichen Itza. When I passed through the arch, I felt like I had entered the ancient city.

Ek Balam is a very compact site. Although it was a larger city, only the center of it, the main plaza has been excavated, which covers about one square mile. This makes it very easy to walk, though. A large arch stands at the entrance of the city, with the remains of a sac-be going through it. The sac-be, or ancient Mayan road (translated as “white road”, due to the color of the limestone that it had been constructed from), connected Ek Balam to other sites, like Coba and Chichen Itza. When I passed through the arch, I felt like I had entered the ancient city. The Acropolis is definitely one of the most impressive structure in all of the Yucatan, a palace and pyramid in one. Though not as tall as Nohuch Mul in Coba, it is much larger overall, measuring 480 ft in length, 180 ft in width and 96 ft in height. Since it has been excavated, it is definitely the most spectacular, with all of the intricately carved figures, unlike any other we’ve seen in all of Yucatan, standing on its walls. The palace has six levels, and at the entrance a monster-like figure, possibly a jaguar, with huge carved teeth is guarding the entrance to the Underworld, the place the Ancient Maya went after death.

The Acropolis is definitely one of the most impressive structure in all of the Yucatan, a palace and pyramid in one. Though not as tall as Nohuch Mul in Coba, it is much larger overall, measuring 480 ft in length, 180 ft in width and 96 ft in height. Since it has been excavated, it is definitely the most spectacular, with all of the intricately carved figures, unlike any other we’ve seen in all of Yucatan, standing on its walls. The palace has six levels, and at the entrance a monster-like figure, possibly a jaguar, with huge carved teeth is guarding the entrance to the Underworld, the place the Ancient Maya went after death.

There is no Mayan site without at least one stelae, a large standing stone, filled with drawing and writing, and Ek Balam is no exception. The one here depicts a ruler, with the hieroglyphic writing around his figure, erected in honor of Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’. Writing in stone was very important to the Maya. They have erected stelae in every known site. It was a way for them to record history and preserve their past. They have also written codices or books, however, most of those didn’t survive, burned by the Spaniards or just disappeared in the jungle, so stelae are very important for the study the Mayan writing and history. They were usually erected to commemorate a moment in history, a moment important to someone, mostly to the rulers of the cities. Because of this, stelae have a figure of the ruler they are talking about, with the important dates in his life. They have the date of his birth, of his accession as a ruler, some important dates of his rule, and finally the date of his death or descend into the Underworld.

There is no Mayan site without at least one stelae, a large standing stone, filled with drawing and writing, and Ek Balam is no exception. The one here depicts a ruler, with the hieroglyphic writing around his figure, erected in honor of Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’. Writing in stone was very important to the Maya. They have erected stelae in every known site. It was a way for them to record history and preserve their past. They have also written codices or books, however, most of those didn’t survive, burned by the Spaniards or just disappeared in the jungle, so stelae are very important for the study the Mayan writing and history. They were usually erected to commemorate a moment in history, a moment important to someone, mostly to the rulers of the cities. Because of this, stelae have a figure of the ruler they are talking about, with the important dates in his life. They have the date of his birth, of his accession as a ruler, some important dates of his rule, and finally the date of his death or descend into the Underworld.