by Darlene Foster

We enter the harbour of Messina, greeted by a golden lady perched on top of a very tall column. Inscribed at the base are the words – “Vos et ipsam cictatem benedicimus”. This sparks my curiosity and I’m determined to learn more about this edifice guarding the port. The heavy rain does not deter me as I leave the boat to explore. I am excited to be in Sicily for the first time.

It has been my experience that a stop at a cathedral is always a good place to start. One can learn much about a city from its cathedrals and churches. It is also a good way to get of the rain. As I approach the Duomo de Capanile, I am intrigued by the massive bronze front door embossed with biblical scenes. My breath is taken away when I enter the vast central nave lined with marble pillars and archways. Inside the alcoves are life sized marble statues of the disciples and apostles. In an elaborate setting at the end of the nave is an image of the Madonna of the Letter, the patron saint of the city. A thick silver overlay, with the faces of the Madonna and child cut out, covers the painting.

I visit the gift shop to buy postcards and ask questions. The friendly shop keeper is happy to oblige a curious Canadian. She explains that the words under the Madonna at the entrance of the port translate into – “We bless you and the city.” It is believed that this message had been written in a letter to the people of Messina by the Virgin Mary when they converted to Christianity in 42 AD, after a visit from the apostle Paul. This explains why she is called Madonna della Lettera or Madonna of the Letter. I purchase a ticket for five euros to visit the museum and attached clock tower.

I visit the gift shop to buy postcards and ask questions. The friendly shop keeper is happy to oblige a curious Canadian. She explains that the words under the Madonna at the entrance of the port translate into – “We bless you and the city.” It is believed that this message had been written in a letter to the people of Messina by the Virgin Mary when they converted to Christianity in 42 AD, after a visit from the apostle Paul. This explains why she is called Madonna della Lettera or Madonna of the Letter. I purchase a ticket for five euros to visit the museum and attached clock tower.

The museum is small, with a few interesting pieces including an impressive golden manta created in 1668. It is similar to the silver covering on the image in the nave with the faces cut out, except in gold and decorated with many jewels. I return to the gift shop with more questions. The accommodating shop keeper explains that on special occasions, the silver covering, is replaced with the one in gold. It is common to cover sacred images with silver or gold robes, leaving only the faces uncovered. Fascinating.

I venture next door to climb the 236 steps to the top of the bell tower. It is worth every step. This belfry houses the largest and most complex mechanical and astronomical clock in the world. On the landings I am able to view, from the inside, the amazing mechanically animated bronze images that rotate on the façade of the tower at the stroke of noon. At the top levels hang the massive bells that ring out the time. I am fortunate I timed my visit between the ringing of the bells. Once at the top, I am rewarded with a splendid view of the city from all four directions. The rain has stopped and the sun is out in full force. I feel I am in heaven, or close to it. I take my time descending, in order to have a better look at the intricate figures, aided by explanations on boards in English as well as Italian. The carousel of life, composed of four golden life size figures representing childhood, youth, maturity and old age, has death in the form of a skeleton following behind. Biblical scenes are depicted on other carousels and changed according to the liturgical calendar. One scene is dedicated to the Madonna of the Letter, where an angel brings the letter to the Virgin Mary followed by St. Paul and the ambassadors who bow when passing in front of the virgin.

I venture next door to climb the 236 steps to the top of the bell tower. It is worth every step. This belfry houses the largest and most complex mechanical and astronomical clock in the world. On the landings I am able to view, from the inside, the amazing mechanically animated bronze images that rotate on the façade of the tower at the stroke of noon. At the top levels hang the massive bells that ring out the time. I am fortunate I timed my visit between the ringing of the bells. Once at the top, I am rewarded with a splendid view of the city from all four directions. The rain has stopped and the sun is out in full force. I feel I am in heaven, or close to it. I take my time descending, in order to have a better look at the intricate figures, aided by explanations on boards in English as well as Italian. The carousel of life, composed of four golden life size figures representing childhood, youth, maturity and old age, has death in the form of a skeleton following behind. Biblical scenes are depicted on other carousels and changed according to the liturgical calendar. One scene is dedicated to the Madonna of the Letter, where an angel brings the letter to the Virgin Mary followed by St. Paul and the ambassadors who bow when passing in front of the virgin.

The vibrant plaza in front of the cathedral holds the gorgeous Fountain of Orion. A great place to view the clock tower from the outside and watch it come to life, should you be there at noon. I remove my raincoat and wander the streets. I find an iron worker creating figures in front of his shop called Hollywood. Many sculptures are scattered throughout the town including an imposing conquistador. The picturesque Church of the Catalans, built before Norman times on a pagan site dedicated to the god Neptune, provides different views from each side. A quote from Shakespeare catches my eye, “I learn in this letter that Don Pedro of Arragon comes this night to Messina… He hath an uncle in Messina will be much glad of it.” from Much Ado About Nothing.

The vibrant plaza in front of the cathedral holds the gorgeous Fountain of Orion. A great place to view the clock tower from the outside and watch it come to life, should you be there at noon. I remove my raincoat and wander the streets. I find an iron worker creating figures in front of his shop called Hollywood. Many sculptures are scattered throughout the town including an imposing conquistador. The picturesque Church of the Catalans, built before Norman times on a pagan site dedicated to the god Neptune, provides different views from each side. A quote from Shakespeare catches my eye, “I learn in this letter that Don Pedro of Arragon comes this night to Messina… He hath an uncle in Messina will be much glad of it.” from Much Ado About Nothing.

I stumble upon an overgrown archaeological dig behind a municipal building. I have the place to myself and imagine what it was like when Messina was a smaller Roman town. Signs, explaining the dig and what was discovered, are in Italian but I get the idea.

Messina has always been the main portal to Sicily. Founded by the Greeks in the eighth century BC, the influence of Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans and Swabians, who have landed on these shores over the years, contributes to the rich culture.

Messina has always been the main portal to Sicily. Founded by the Greeks in the eighth century BC, the influence of Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans and Swabians, who have landed on these shores over the years, contributes to the rich culture.

The city has been subject to many earthquakes over the centuries and I find it amazing that so much history has been left intact. One young shop keeper tells me there aren’t many old things in her city as so much has had to be rebuilt or restored due to damages from earthquakes. The last major earthquake was in 1908. The city also suffered much damage during World War II. They have done an impressive job of keeping the flavour of this city alive.

I purchase a bag of Italian pasta, a great reminder of my enjoyable time in this amazing Sicilian city. As the ship leaves port, I wave goodbye to Our Lady of the Letter with her comforting message sent to the citizens two thousand years ago.

If You Go:

♦ You can get to Messina on a short ferry ride across the Straits of Messina by car, train or bus from one of two ports in Calabria, or on a longer ferry ride from Salerno, just south of Naples. – See more at: www.reidsitaly.com.

♦ Some cruise ships stop at Messina or you can arrive by your own yacht.

♦ Messina is easy to walk around, but there are bus, train, and horse and buggy tours available from the plaza in front of the cathedral for 10 to 20 euros.

♦ Arranging your visit around noon would enable you to see the clock tower come to life.

♦ To climb the clock tower a ticket for 5 euros is required which includes entrance to the museum in the cathedral. This can be purchased in the gift shop of the cathedral

Best Sicilian Offer: Private Tour of Etna – Alcantara – Godfather – Food and Wine from Messina

About the author:

Darlene Foster is a dedicated writer and traveler. She is the author of a series of books featuring Amanda, a spunky young girl who loves to travel to interesting places such as the United Arab Emirates, Spain, England and Alberta, where she always has an adventure. Darlene divides her time between the west coast of Canada and the Costa Blanca of Spain. www.darlenefoster.ca

All photos are by Darlene Foster:

Madonna of the Letter

Clock Tower Bells

Carousel of Life

Church of the Catalans

The Church and Tower

As it happens, our grandson is a Sapper in the Royal Engineers, and Gibraltar has a proud place in their history. Indeed, when they’re not Royal Engineering around the globe somewhere, their home, in Surrey, is called Gibraltar Barracks.

As it happens, our grandson is a Sapper in the Royal Engineers, and Gibraltar has a proud place in their history. Indeed, when they’re not Royal Engineering around the globe somewhere, their home, in Surrey, is called Gibraltar Barracks.

The whole Spanish peninsula was ceded to the Romans after the Second Punic War, in 150 BC; the Romans, called the Rock Mons Calpe.

The whole Spanish peninsula was ceded to the Romans after the Second Punic War, in 150 BC; the Romans, called the Rock Mons Calpe. It owes its present name to the Moors, who captured it in the 8th Century. They called it Jebel Tariq (Tariq’s Hill), after the Moorish commander Tariq ibn Zeyad. Over time, it became … Gibraltar.

It owes its present name to the Moors, who captured it in the 8th Century. They called it Jebel Tariq (Tariq’s Hill), after the Moorish commander Tariq ibn Zeyad. Over time, it became … Gibraltar. However, this arrangement has long been a bone of contention between Britain and Spain … but, in referenda held in 1967, and again in 2002, the Gibraltarians elected to remain a British territory.

However, this arrangement has long been a bone of contention between Britain and Spain … but, in referenda held in 1967, and again in 2002, the Gibraltarians elected to remain a British territory. Europa Point is the southernmost point. and here is the Trinity lighthouse, the only one outside the British Isles administered by Trinity House. Here, also, is a picturesque mosque endowed by the King of Saudi Arabia.

Europa Point is the southernmost point. and here is the Trinity lighthouse, the only one outside the British Isles administered by Trinity House. Here, also, is a picturesque mosque endowed by the King of Saudi Arabia.

Most of the resultant rubble was dumped in the bay … to eventually become the site of the airfield runway. And, that’s no ordinary runway. It used to be that the road had to be closed to allow aircraft to take off and land, but now, there’s a tunnel under it.

Most of the resultant rubble was dumped in the bay … to eventually become the site of the airfield runway. And, that’s no ordinary runway. It used to be that the road had to be closed to allow aircraft to take off and land, but now, there’s a tunnel under it.

On the Aria, all meals of 14 breakfasts, 14 lunches and 14 dinners included wine, beer or soda. A cold/hot buffet was available for all meals and the chef prepared a ‘local specialty’ dinner in the evening. Open seating was the standard in the restaurant. The four courses served at lunch and dinner included soup, salad, entree and dessert. The servers were very attentive to the needs of the guests and always wished us a “Bon appetite” before the entre. While on the ship, a tour of the galley offered guests the opportunity to see where the food was prepared. It was amazing to see the small area where all the chefs prepared, plated and served the meals. A tour of the pilot room was very informative.

On the Aria, all meals of 14 breakfasts, 14 lunches and 14 dinners included wine, beer or soda. A cold/hot buffet was available for all meals and the chef prepared a ‘local specialty’ dinner in the evening. Open seating was the standard in the restaurant. The four courses served at lunch and dinner included soup, salad, entree and dessert. The servers were very attentive to the needs of the guests and always wished us a “Bon appetite” before the entre. While on the ship, a tour of the galley offered guests the opportunity to see where the food was prepared. It was amazing to see the small area where all the chefs prepared, plated and served the meals. A tour of the pilot room was very informative.

The Great Rivers Cruise began in Amsterdam and cruised to Cologne, Koblenz, Heidelberg and Wertheim, a fairy-tale town where the Main and Tauber Rivers meet. Onward, we cruised to Wurzburg on the Main in Bavaria, walking the bridge with wine in hand and Bamberg, a city on the Main River in Bavaria where the onions are huge and the cold smoky bacon beer was a welcome delight. Nuremberg explored the past and tragic time in history. Regensburg, Passau, and Vienna completed our cruise. Optional tours to Rothenburg on the Tauber River, the Bavaria: Baroque & Beer, with beer, pretzels and mustard and cruising thru the beautiful Danube Gorge to the Weltenburg Monastery provided more opportunities to explore the region. In Melk, a bus transported us to the magnificent Abbey and Baroque Church. Sailing through the Wachau Valley we reached Vienna, an Imperial City, for a Musical Tour of Vienna.

The Great Rivers Cruise began in Amsterdam and cruised to Cologne, Koblenz, Heidelberg and Wertheim, a fairy-tale town where the Main and Tauber Rivers meet. Onward, we cruised to Wurzburg on the Main in Bavaria, walking the bridge with wine in hand and Bamberg, a city on the Main River in Bavaria where the onions are huge and the cold smoky bacon beer was a welcome delight. Nuremberg explored the past and tragic time in history. Regensburg, Passau, and Vienna completed our cruise. Optional tours to Rothenburg on the Tauber River, the Bavaria: Baroque & Beer, with beer, pretzels and mustard and cruising thru the beautiful Danube Gorge to the Weltenburg Monastery provided more opportunities to explore the region. In Melk, a bus transported us to the magnificent Abbey and Baroque Church. Sailing through the Wachau Valley we reached Vienna, an Imperial City, for a Musical Tour of Vienna. This is not a trip for individuals who have great difficulty walking. Some individuals used scooters and walkers and were accustomed to the cobblestone streets and stairways. During the evenings, we sailed the rivers to a new destination and the tours would begin. Some tours began at the water edge and was a half-day trek through the medieval cities walking on the old cobblestone streets always watching out for bicyclists. Other tours required a comfortable coach ride to the sights. The Grand Cruises employs four Program Directors, men, and women from the area where they have lived. They are very knowledgeable about the history of the country and city, the architecture, museums, churches, castles, UNESCO sites, city life, and stories told over the ages. Some cities provided additional city guides and we met people who lived in the city and they spoke with us about their lives, the war, and refugee crisis – some rather controversial topics. The educational focus of the Grand Circle Cruise Line makes it a leader in river cruising worldwide and the recipient of numerous awards. Every Program Director had approximately 25 guests and were given headsets to hear the director while walking in the cities.

This is not a trip for individuals who have great difficulty walking. Some individuals used scooters and walkers and were accustomed to the cobblestone streets and stairways. During the evenings, we sailed the rivers to a new destination and the tours would begin. Some tours began at the water edge and was a half-day trek through the medieval cities walking on the old cobblestone streets always watching out for bicyclists. Other tours required a comfortable coach ride to the sights. The Grand Cruises employs four Program Directors, men, and women from the area where they have lived. They are very knowledgeable about the history of the country and city, the architecture, museums, churches, castles, UNESCO sites, city life, and stories told over the ages. Some cities provided additional city guides and we met people who lived in the city and they spoke with us about their lives, the war, and refugee crisis – some rather controversial topics. The educational focus of the Grand Circle Cruise Line makes it a leader in river cruising worldwide and the recipient of numerous awards. Every Program Director had approximately 25 guests and were given headsets to hear the director while walking in the cities.

The Rhine River journey from Koblenz, Germany to Ruedeshiem, Germany revealed many castles, 24 in all. The 760 mile voyage up the Rhine River moved at 9½ mph upstream. Each village had a castle on a high hilltop for protection in ages past and a church or two. Along the river, there appeared fortresses, ruins, castles and the legendary Lorelei statue and rocks.

The Rhine River journey from Koblenz, Germany to Ruedeshiem, Germany revealed many castles, 24 in all. The 760 mile voyage up the Rhine River moved at 9½ mph upstream. Each village had a castle on a high hilltop for protection in ages past and a church or two. Along the river, there appeared fortresses, ruins, castles and the legendary Lorelei statue and rocks. The cruise offered multiple opportunities for enrichment learning. Speakers, singers, dancers and a glass blowing demonstration entertained guests while in port before leaving and in the evening, a crew show on the lounge floor demonstrated additional talents of the crew.

The cruise offered multiple opportunities for enrichment learning. Speakers, singers, dancers and a glass blowing demonstration entertained guests while in port before leaving and in the evening, a crew show on the lounge floor demonstrated additional talents of the crew.

The heavy wooden door closed and I stood surrounded by silence. Flying anywhere from Australia takes a long time, and after a night and a day and a night I was exhausted. Tired and befuddled, I emerged into the chaos of Rome. I finally found a taxi, with a driver who careened down tiny streets where footpaths were more a suggestion than reality.

The heavy wooden door closed and I stood surrounded by silence. Flying anywhere from Australia takes a long time, and after a night and a day and a night I was exhausted. Tired and befuddled, I emerged into the chaos of Rome. I finally found a taxi, with a driver who careened down tiny streets where footpaths were more a suggestion than reality. Rooms may be simple, but this does not imply austerity. Convents and monasteries are often to be found in Renaissance palazzos, Medieval walled towns or set amongst lavender fields and vineyards. Many hide artistic treasures; a painting by Rubens, or walls adorned by Fra Angelico. Each religious house has its own character, such as the monastery Convento Sant’Agostino in San Gimigiano which refused entry to HRH The Prince of Wales when he arrived after closing time. (Although probably apocryphal, the story alone makes the place worth a detour.)

Rooms may be simple, but this does not imply austerity. Convents and monasteries are often to be found in Renaissance palazzos, Medieval walled towns or set amongst lavender fields and vineyards. Many hide artistic treasures; a painting by Rubens, or walls adorned by Fra Angelico. Each religious house has its own character, such as the monastery Convento Sant’Agostino in San Gimigiano which refused entry to HRH The Prince of Wales when he arrived after closing time. (Although probably apocryphal, the story alone makes the place worth a detour.)

In Florence, the Casa Santo Nome di Jesu is in a 15th C palazzo. I reached my room via a marble staircase, complete with trompe l’oil ceiling of putti and plaster relief. The window overlooked a large garden, complete with kiwi fruit, persimmons, pomegranates, grape vines and wisterias, with trunks as thick as my body. The arbour was a perfect place to sit and pass the afternoon when exhausted by sightseeing.

In Florence, the Casa Santo Nome di Jesu is in a 15th C palazzo. I reached my room via a marble staircase, complete with trompe l’oil ceiling of putti and plaster relief. The window overlooked a large garden, complete with kiwi fruit, persimmons, pomegranates, grape vines and wisterias, with trunks as thick as my body. The arbour was a perfect place to sit and pass the afternoon when exhausted by sightseeing. Most convents provide breakfast – fresh rolls and strong coffee are a staple – and often dinner as well. In some, monks still make wine to recipes centuries-old. My first time in Venice, my choice lay at the end of a maze of cobble-stoned side streets and piazzas. The Instituto San Giuseppe stands beside a canal, with a door opening directly onto the water. As I crossed a small limestone bridge a gondola came to a boisterous stop to collect passengers.

Most convents provide breakfast – fresh rolls and strong coffee are a staple – and often dinner as well. In some, monks still make wine to recipes centuries-old. My first time in Venice, my choice lay at the end of a maze of cobble-stoned side streets and piazzas. The Instituto San Giuseppe stands beside a canal, with a door opening directly onto the water. As I crossed a small limestone bridge a gondola came to a boisterous stop to collect passengers. My room was simple and clean. The windows opened onto a terracotta skyline, with clothes strung on a line between two buildings. Across a flower-strewn courtyard a woman in black was busy in her kitchen, filling the air with delicious aromas. Every evening an extended family materialised for dinner. Geraniums hung everywhere in pots. In the distance a camponile tolled away the hours while towering (at a slight angle) over the other buildings,

My room was simple and clean. The windows opened onto a terracotta skyline, with clothes strung on a line between two buildings. Across a flower-strewn courtyard a woman in black was busy in her kitchen, filling the air with delicious aromas. Every evening an extended family materialised for dinner. Geraniums hung everywhere in pots. In the distance a camponile tolled away the hours while towering (at a slight angle) over the other buildings, The next essential is catching a boat from the airport to the city, either on the public vaporetto, or by a much faster private boat. Our vessel was all streamlined wood, the skipper as sleek and polished as his vessel. Despite a complete lack of Italian, as soon as my husband began admiring the boat (being a long-time sailor himself) the skipper happily displayed the boat’s paces. As the rain finally poured down and visibility vanished, he raced along the narrow channel to the city, overtaking every other boat in a shower of spray.

The next essential is catching a boat from the airport to the city, either on the public vaporetto, or by a much faster private boat. Our vessel was all streamlined wood, the skipper as sleek and polished as his vessel. Despite a complete lack of Italian, as soon as my husband began admiring the boat (being a long-time sailor himself) the skipper happily displayed the boat’s paces. As the rain finally poured down and visibility vanished, he raced along the narrow channel to the city, overtaking every other boat in a shower of spray.

The entrance to the convent Canossian Institute San Trovaso lies on a pretty canal, devoid of tourists. Being in the Dorsoduro area of Venice, the streets are far less crowded than the more popular areas, locals outnumber the tourists, and at night the area is quiet. An elderly nun opened the door, and we walked into tranquility. She led us through an inner courtyard, where some other guests sat sipping wine as their kids feasted on gelato.

The entrance to the convent Canossian Institute San Trovaso lies on a pretty canal, devoid of tourists. Being in the Dorsoduro area of Venice, the streets are far less crowded than the more popular areas, locals outnumber the tourists, and at night the area is quiet. An elderly nun opened the door, and we walked into tranquility. She led us through an inner courtyard, where some other guests sat sipping wine as their kids feasted on gelato. Convents and monastery are not only in cities, but also in idyllic countryside settings. Stays are not restricted to Italy, and some are to be found in the most unexpected of places. An example is the 12th century monastery Kriva Palanka, hidden in the Osogovo Mountains of Macedonia [TOP PHOTO]. It is worth a visit for the medieval frescoes alone.

Convents and monastery are not only in cities, but also in idyllic countryside settings. Stays are not restricted to Italy, and some are to be found in the most unexpected of places. An example is the 12th century monastery Kriva Palanka, hidden in the Osogovo Mountains of Macedonia [TOP PHOTO]. It is worth a visit for the medieval frescoes alone.

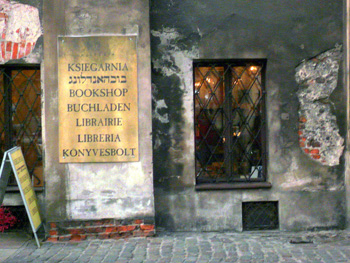

In March 1941, the Germans forced all Krakow Jews to resettle in the newly created ghetto of Kazimierz. The Nazis liquidated it only two years later on March 13, 1943. Most of the 17,000 inhabitants perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Today Krakow has only about 200 Jewish residents.

In March 1941, the Germans forced all Krakow Jews to resettle in the newly created ghetto of Kazimierz. The Nazis liquidated it only two years later on March 13, 1943. Most of the 17,000 inhabitants perished in the Nazi concentration camps. Today Krakow has only about 200 Jewish residents. Kazimirez is not beautiful; many of its buildings are run down. A few night clubs have emerged around the Square. We enjoyed just sitting and people watching… modern day residents and a few Jews dressed in shawls and yarmulkes. And, of course, the foreign tourists.

Kazimirez is not beautiful; many of its buildings are run down. A few night clubs have emerged around the Square. We enjoyed just sitting and people watching… modern day residents and a few Jews dressed in shawls and yarmulkes. And, of course, the foreign tourists.

The next thing on our list, however, was to sample some of the local food. There was no shortage of Jewish themed restaurants and shops.

The next thing on our list, however, was to sample some of the local food. There was no shortage of Jewish themed restaurants and shops. Another interesting feature are the walls in the prayer hall. Prayers have been painted on the walls for worshipers who couldn’t afford prayer books. Most readings have even been translated into English. A plaque outside states the synagogue was constructed in 1638, so there is some serious history attached to this place of worship.

Another interesting feature are the walls in the prayer hall. Prayers have been painted on the walls for worshipers who couldn’t afford prayer books. Most readings have even been translated into English. A plaque outside states the synagogue was constructed in 1638, so there is some serious history attached to this place of worship. In addition to the Jewish element, Christianity also had a role in Kazimirez. The Church of Corpus Christi has an awesome historical interior. There are stalls going back to 1629, the altarpiece of 1634, and the ornate mid-18th-century pulpit.

In addition to the Jewish element, Christianity also had a role in Kazimirez. The Church of Corpus Christi has an awesome historical interior. There are stalls going back to 1629, the altarpiece of 1634, and the ornate mid-18th-century pulpit.