by Millie Slavidou

Every country has its traditions and its history, and we all have different approaches to entertainment. Music, however, seems to be universal. All peoples have some form of music, and it has been called the language of the soul. And where there is music, there is often dance. People of all social classes dance, although the styles may differ, and these days what was once regarded as the province of peasants has come to be regarded as an important national treasure.

Folk dancing, or the traditional dances of the ordinary people, is something that can be seen all over Greece, and is a very significant part of local tradition. Each region has its own dances, although there are some dances that are common to all, such as the 12-step syrtos kalamatianos. Some of them may appear slow and staid, while others are faster, with intricate steps, and even jumps and very particular moves, such as touching the floor, bending the knee and swaying; there is a great deal of variety. If you travel to Crete and get the opportunity to watch the very impressive Pentozali dance, with its leaps and twirls, this is not to be missed.

Folk dancing, or the traditional dances of the ordinary people, is something that can be seen all over Greece, and is a very significant part of local tradition. Each region has its own dances, although there are some dances that are common to all, such as the 12-step syrtos kalamatianos. Some of them may appear slow and staid, while others are faster, with intricate steps, and even jumps and very particular moves, such as touching the floor, bending the knee and swaying; there is a great deal of variety. If you travel to Crete and get the opportunity to watch the very impressive Pentozali dance, with its leaps and twirls, this is not to be missed.

But we are going to concentrate here on the province of Evros. A place where each village is steeped in tradition, and the local costumes reflect that, with different colours, embroidery styles and other details revealing the locations.

But we are going to concentrate here on the province of Evros. A place where each village is steeped in tradition, and the local costumes reflect that, with different colours, embroidery styles and other details revealing the locations.

During the Carnival season, generally in February, starting 8 or 9 weeks before Easter, many villages organize dances outside in public squares. These may be the gaitanaki, a dance involving ribbons that are twirled around a pole, or the syrtos, a classic Greek folk dance based on twelve steps, with some local variation in whether hands go up or down, and whether you should step forwards or backwards in the final steps. You may recognize this one from film or TV.

In Pentalofos, a village high up in the hills of northern Evros, close to the border with Bulgaria, I attended a dance at Easter. Local musicians, often playing traditional folk instruments such as the gaida, a local version of the bagpipes, come out into the central square of the village. The first year that I went, they were accompanied by a group of people wearing traditional costumes, but it seems that this is not always the case, as there were no costumes the following year. These people, whether dressed up or not, are dancers, and they begin the dance, to a great deal of applause and cheering from the crowds gathered there. After the first two dances, everyone else starts to join in. It is great fun, and the atmosphere is one of celebration and joy.

In Pentalofos, a village high up in the hills of northern Evros, close to the border with Bulgaria, I attended a dance at Easter. Local musicians, often playing traditional folk instruments such as the gaida, a local version of the bagpipes, come out into the central square of the village. The first year that I went, they were accompanied by a group of people wearing traditional costumes, but it seems that this is not always the case, as there were no costumes the following year. These people, whether dressed up or not, are dancers, and they begin the dance, to a great deal of applause and cheering from the crowds gathered there. After the first two dances, everyone else starts to join in. It is great fun, and the atmosphere is one of celebration and joy.

One local dance that I particularly enjoyed was dendritsi, a dance with skipping steps and some very slight kicks, or raising the foot. Everyone joins hands in an enormous chain or circle to dance and there is a great sense of community, with people of all ages taking part. All are welcome. And not to worry if you don’t know the steps; the locals are happy to show you the ropes and no one minds if you put a foot wrong.

A major event in the folk dancing calendar is the festival that takes place in Alexandroupoli, the largest town in Evros, every summer, generally towards the end of June. A show is put on by local dancing clubs in the open-air theatre, which is close to the sea and surrounded by pine trees. In such a setting, the atmosphere is amazing. All the participants wear impressive traditional costumes, all different to reflect the places where their dances originated. Last year, over 250 dancers took part, including children as young as 5 years old. Live music fills the incredibly crowded theatre, with people sitting on the steps and standing all the way around the stage, tightly packed. Only those who come early will have a seat; the show is extremely popular.

A major event in the folk dancing calendar is the festival that takes place in Alexandroupoli, the largest town in Evros, every summer, generally towards the end of June. A show is put on by local dancing clubs in the open-air theatre, which is close to the sea and surrounded by pine trees. In such a setting, the atmosphere is amazing. All the participants wear impressive traditional costumes, all different to reflect the places where their dances originated. Last year, over 250 dancers took part, including children as young as 5 years old. Live music fills the incredibly crowded theatre, with people sitting on the steps and standing all the way around the stage, tightly packed. Only those who come early will have a seat; the show is extremely popular.

The dancers parade in across the stage, in time with a popular, well-known song. Members of the audience join in with the singing; everywhere people are smiling. Then the individual dances begin. These range from the relatively simple performances by the youngest children – who are cheered and clapped tremendously – to complicated, intricate steps and jumps. Each dance is announced before it begins, so the audience knows what they are all called. There are two singers, each keeping to a particular style and alternating to give each other a rest, as the performances go on for well over three hours. It is a truly incredible experience.

Folk dancing is firmly rooted in Greece’s cultural heritage, and it is hard to imagine the country without it. I see it as part of the colour and patchwork of life in Greece: celebrations mean dancing, and public places are for dancing in. And what is life for if not to be enjoyed and celebrated?

If You Go:

If You Go:

Greek Folk Dances:

Greek Dances

Portrait of the Greek dance

Travel: Evros, Greece

Greek Travel – Evros

Visit Greece – Evros River

About the author:

Millie Slavidou is a writer and a translator. As well as being a frequent contributor to Jump Mag, she is the author of the InstaExplorer series for pre-teens, which takes young readers on a journey round the world, experiencing local cultures, traditions and languages along the way. jumpbooks.co.uk/category/millie-slavidou

All photos are by Millie Slavidou.

Before I set off on my three week trip to Galicia, Spain’s green, wet and wild northern province, I had a vague idea who Rosalia de Castro was, but none whatsoever about a place called Padron.

Before I set off on my three week trip to Galicia, Spain’s green, wet and wild northern province, I had a vague idea who Rosalia de Castro was, but none whatsoever about a place called Padron. Still, my main interest was Rosalia de Castro. Even before I went to Galicia, I was familiar with the idiosyncratic concept of moriña. It’s best translated as a deeply felt longing of every Galego for his home and roots. An example: a Galego who has to move to – say – Madrid, considers himself an ex-pat. Another word for moriña is saludade and that’s also the Leitmotiv of Rosalia’s work.

Still, my main interest was Rosalia de Castro. Even before I went to Galicia, I was familiar with the idiosyncratic concept of moriña. It’s best translated as a deeply felt longing of every Galego for his home and roots. An example: a Galego who has to move to – say – Madrid, considers himself an ex-pat. Another word for moriña is saludade and that’s also the Leitmotiv of Rosalia’s work. Moreover, although basically a romantic, she strongly opposed abuse of authority and was a strong defender of women’s rights. And she made her voice heard. Married to Manuel Murgia, a historian, academic and journalist, she had seven children despite a very fragile health. She died at age 48 in 1885 in her home in Padron.

Moreover, although basically a romantic, she strongly opposed abuse of authority and was a strong defender of women’s rights. And she made her voice heard. Married to Manuel Murgia, a historian, academic and journalist, she had seven children despite a very fragile health. She died at age 48 in 1885 in her home in Padron.

The stone cottage is visible, but only just, above the garden full of trees and flowers which Rosalia tended herself. She used to sit among blooming camellia bushes on a carved stone bench and dream up new poems. The whole scene is so romantic that one feels like writing a love poem there and then.

The stone cottage is visible, but only just, above the garden full of trees and flowers which Rosalia tended herself. She used to sit among blooming camellia bushes on a carved stone bench and dream up new poems. The whole scene is so romantic that one feels like writing a love poem there and then. The kitchen with its woodstove and iron kettles looks no different to any other farmhouse kitchen at the time. Her bedroom is spartan, still with her clothes hanging in the closet. Next door is her study with the desk and writing utensils. I wished I could just have sat down, hoping to be infused by her creative spirit.

The kitchen with its woodstove and iron kettles looks no different to any other farmhouse kitchen at the time. Her bedroom is spartan, still with her clothes hanging in the closet. Next door is her study with the desk and writing utensils. I wished I could just have sat down, hoping to be infused by her creative spirit.

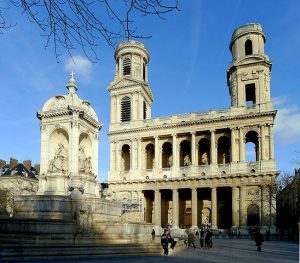

History, as it’s studied in school, can be a tough concept to wrap your head around. Centuries can be covered in days; weeks can be spent on one event. For many, the time when prehistoric man was living and roaming the caverns and fields and mountains of the Earth gets scrambled with the era of the dinosaurs. I had a hard time figuring out a real timeline when I was in high school history class. In fact, it’s only been in living history, in exploring the places where these things actually took place, pressing my hand against the wall of a building that once witnessed a revolution, a king’s court dance, a meeting of the French Resistance, that I’ve been able to understand, even a little bit, the events, the moments, the people that came before me.

History, as it’s studied in school, can be a tough concept to wrap your head around. Centuries can be covered in days; weeks can be spent on one event. For many, the time when prehistoric man was living and roaming the caverns and fields and mountains of the Earth gets scrambled with the era of the dinosaurs. I had a hard time figuring out a real timeline when I was in high school history class. In fact, it’s only been in living history, in exploring the places where these things actually took place, pressing my hand against the wall of a building that once witnessed a revolution, a king’s court dance, a meeting of the French Resistance, that I’ve been able to understand, even a little bit, the events, the moments, the people that came before me. But somehow, prehistory is harder to get a grasp on. How can you look at a place and imagine nothing, none of the buildings or houses or even roads, none of the modernity that seems to exist wherever you go today? It’s difficult, near impossible, and yet I found it much easier to wrap my head around the prehistory as I journeyed through Southern France.

But somehow, prehistory is harder to get a grasp on. How can you look at a place and imagine nothing, none of the buildings or houses or even roads, none of the modernity that seems to exist wherever you go today? It’s difficult, near impossible, and yet I found it much easier to wrap my head around the prehistory as I journeyed through Southern France. Tautavel Man is a 450,000-year-old fossil, a proposed subspecies of Homo erectus, one of our true ancestors. I find it incredibly hard to fathom the time between when he was born and when I was, and yet that’s the point of the museum in the town of Tautavel, which explores the discoveries uncovered in the cave and offers a unique view of life in this region at Tautavel Man’s time.

Tautavel Man is a 450,000-year-old fossil, a proposed subspecies of Homo erectus, one of our true ancestors. I find it incredibly hard to fathom the time between when he was born and when I was, and yet that’s the point of the museum in the town of Tautavel, which explores the discoveries uncovered in the cave and offers a unique view of life in this region at Tautavel Man’s time.

The museum is split into two portions: the first is in the village and offers an exploration of the tools and shelters created by Tautavel man and his contemporaries. Visiting this portion of the museum first allows you to experience some of the wonder that the first archaeologists excavating in the cave above did.

The museum is split into two portions: the first is in the village and offers an exploration of the tools and shelters created by Tautavel man and his contemporaries. Visiting this portion of the museum first allows you to experience some of the wonder that the first archaeologists excavating in the cave above did. The museum is ideal for visits with kids, complete with activities in the summer including teaching participants how to throw a spear or make fire out of stones and moss. But even for adults, these activities are essential to gaining a true glimpse of life in the time of Tautavel Man.

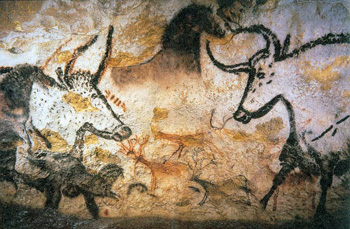

The museum is ideal for visits with kids, complete with activities in the summer including teaching participants how to throw a spear or make fire out of stones and moss. But even for adults, these activities are essential to gaining a true glimpse of life in the time of Tautavel Man. It is in Lascaux that, in 1940, three local teenagers accidentally stumbled upon prehistoric cave paintings, changing the way that we perceive of these “cave” men forever. Soon after their discovery, experts identified the paintings as Paleolithic art, some of the earliest to have ever been discovered. The paintings are far more recent than Tautavel man, at 17,300 years old, and they have long been a draw to this region, not far from Limoges, where art still remains an important element of local life due to the tradition of Limoges porcelain.

It is in Lascaux that, in 1940, three local teenagers accidentally stumbled upon prehistoric cave paintings, changing the way that we perceive of these “cave” men forever. Soon after their discovery, experts identified the paintings as Paleolithic art, some of the earliest to have ever been discovered. The paintings are far more recent than Tautavel man, at 17,300 years old, and they have long been a draw to this region, not far from Limoges, where art still remains an important element of local life due to the tradition of Limoges porcelain.

I went to Lascaux to visit the caves, but like all visitors since the 1960s, I actually visited Lascaux II, a replica of the original cave, which was closed when experts realized that lichen had become prevalent due to the frequency of visits and risked destroying the paintings. But visiting Lascaux II is not discouraging; after buying our tickets in the village of Montignac below and driving up to the caves, we are taken on a journey through time.

I went to Lascaux to visit the caves, but like all visitors since the 1960s, I actually visited Lascaux II, a replica of the original cave, which was closed when experts realized that lichen had become prevalent due to the frequency of visits and risked destroying the paintings. But visiting Lascaux II is not discouraging; after buying our tickets in the village of Montignac below and driving up to the caves, we are taken on a journey through time. The guide goes into details that never would have occurred to me over the next 45 minutes: how the paints were made by the artist, who shows considerable skill in representing the animals that existed around him including horses, cattle and stags. As we wander through the caves, I almost forget that this is a facsimile, until the guide explains the feat of reproducing the caves using a concrete base and the recreation of the same sorts of paints that would have been used for the originals. Lascaux II is accurate up to a couple of millimeters to the original.

The guide goes into details that never would have occurred to me over the next 45 minutes: how the paints were made by the artist, who shows considerable skill in representing the animals that existed around him including horses, cattle and stags. As we wander through the caves, I almost forget that this is a facsimile, until the guide explains the feat of reproducing the caves using a concrete base and the recreation of the same sorts of paints that would have been used for the originals. Lascaux II is accurate up to a couple of millimeters to the original.