by Elizabeth von Pier

All my life I have traveled with someone. First it was my husband, then after he died, various friends and family. So this was my first solo trip (at the age of sixty-something!). I was meeting family in Italy afterward so somehow that future connection made me feel more comfortable going alone to Paris. Also, I know the city fairly well. So, I rented an apartment for two weeks in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the centrally located St. Germaine des Pres quartier, and set out for the adventure of a lifetime.

I found I enjoyed traveling alone because I could do whatever I wanted whenever I wanted. But dining out was a problem for me because I don’t like to eat out alone. So, for the most part, my dinners were an assortment of take-out foods I got at various stalls and epiceries and I ate by the window of my apartment, watching the Parisian world go by.

My “home” in Paris was a third floor flat overlooking an upscale boulevard. Across the street were two popular and competing cafes, the Cafe de Flore and Les Deux Magots. One morning I watched them set up their tables and chairs getting ready to open for business as the homeless family who spent the night six feet away folded up their blankets, packed their belongings into a cart, cleaned up the debris, and set off down the street.

I typically started my day power-walking in Luxembourg Gardens [TOP PHOTO]. The flowers were still beautiful, even in October. I admired the statues of kings, queens, gods, goddesses, and cherubs holding urns filled with flowers. People picnic on the grass and lovers kiss. One couple was kissing my first time around the park, and was still at it my second time around. Sundays are the biggest day when everything steps up a notch. There are hundreds of joggers doing their laps, groups of people are practicing tai-chi, ponies are lined up waiting to take little ones for a ride, teens are rehearsing dance steps, families are waiting in line to get into the marionette show, children are at the edge of the pond sailing their toy boats, and bands are playing Israeli and other dance music. The big fountain at the southern end is turned on, with its ferocious-looking fish, turtles, horses and goddesses. I left smiling ear-to-ear.

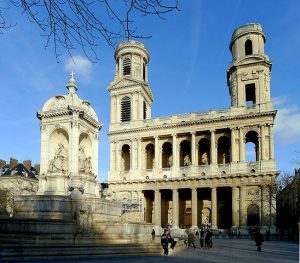

I would pass the Eglise Saint Sulpice, known as the “Notre Dame of the left bank”, on my way to Luxembourg Gardens. Usually there were beggars near the door, holding out weather-worn hands for a few euros. Inside the church are beautiful Delacroix frescoes and outside in the piazza is an elaborate fountain. Little pre-schoolers played at the edge of the fountain laughing and squealing in French. As I walked by, I often heard the bells tolling, calling the faithful to services, a glorious sound to my ears.

I would pass the Eglise Saint Sulpice, known as the “Notre Dame of the left bank”, on my way to Luxembourg Gardens. Usually there were beggars near the door, holding out weather-worn hands for a few euros. Inside the church are beautiful Delacroix frescoes and outside in the piazza is an elaborate fountain. Little pre-schoolers played at the edge of the fountain laughing and squealing in French. As I walked by, I often heard the bells tolling, calling the faithful to services, a glorious sound to my ears.

On occasion, I got mistaken for a local as I pointed some lost tourists in the right direction. But on one of those days, my ego was quickly deflated when a group of art students doing a project on “integration” asked for a photo of me dancing with one of the male students (“integration” of the old and the young, I presume).

I took some time each day to visit one or two of the many attractions of this city. There are way too many to describe, but there were some that especially interested me. I flaneured (strolled) to the lovely Place des Vosges and the Musee Carnavalet, one of the mansion-museums owned by the City of Paris that are free to the public. I shopped at the bookstalls on the Seine and came upon an outdoor exhibit of avant-garde photography. Now I’m wondering if that photo of me dancing with the young student might someday show up in a public venue like this! And of course I walked the Champs d’Elysees, stopping in several car showrooms to see their prototypes and custom one-of-kind models.

It rained one night while I was reading in bed. It was a heavy downpour so I went to a window overlooking the boulevard and everything seemed to be shimmering. The shop windows displaying high fashion were all lit up and reflected in the wide wet sidewalks. And the raindrops looked like sparkling gold in the yellow street lights.

The Musee l’Orangerie has some beautiful works by Monet, including his water lilies. The canvases are magnificent, each 50 to 60 feet long and are mounted right onto the walls. The four paintings capture Monet’s garden in various light. The student quarter is an enjoyable area to wander and get lost in. Rue Mouffetard, one of Paris’ famous market streets with dozens of delightful specialty food shops, is in this area. Nearby is the Grand Mosque de Paris, awe-inspiring and tranquil with tiled arcades, a minaret and an interior patio garden modeled after the Alhambra in Spain.

One Saturday evening there was a free organ recital at Notre Dame. Being in that mammoth cathedral at night with its colossal stone pillars, dark side altars and images of the hunchback and the gargoyles up above was haunting. So was the music. I came back to the flat to see the homeless family across the street return to their usual spot. Later, feeling guilty with a full belly and looking down at them from my lovely, warm and comfortable apartment, I got dressed and went out to give the mother some euros. It was even worse than I thought. There were three sweet little cherubs all under four years old sprawled out, mouths open, sound asleep and snuggling next to her warm body.

One Saturday evening there was a free organ recital at Notre Dame. Being in that mammoth cathedral at night with its colossal stone pillars, dark side altars and images of the hunchback and the gargoyles up above was haunting. So was the music. I came back to the flat to see the homeless family across the street return to their usual spot. Later, feeling guilty with a full belly and looking down at them from my lovely, warm and comfortable apartment, I got dressed and went out to give the mother some euros. It was even worse than I thought. There were three sweet little cherubs all under four years old sprawled out, mouths open, sound asleep and snuggling next to her warm body.

There is a fabulous view from the open-air roof terrace of the Tour Montparnasse, a 59-story modern skyscraper and one of the most hated buildings in Paris. And you avoid the long lines at the Eiffel Tower. I strolled there leisurely and revisited some places I especially loved in the past–the Palais-Royal, a former palace that now houses lovely shops and cafes, Galerie Vivienne, one of Paris’s 19th century covered arcades; and the fabulous Opera House where I sat on the steps and listened to a street performer playing a violin.

I highly recommend going across the river to the Jewish quarter where there is a small take-out joint on rue des Rosiers that makes THE BEST felafel wraps loaded with veggies and sauce. You can’t miss it because there’s always a long line at the take-out counter on the street. Order your wrap and enjoy every morsel as you sit on the curb or lean against the building like everyone else.

One morning, I decided to check out the City Pharmacy close to my flat. French pharmacies are found on every block and identified by a neon green cross. They are both weird and delightful places where you can fill a prescription, but you can’t buy tampons or help yourself to Tylenol; it must be fetched for you by an official Pharmacist in a lab coat. And the walls are covered with shelves and shelves of skincare products, all claiming to re-hydrate, plump and re-rejuvenate. In every narrow aisle, there are at least two “assistants” to point out your flaws and help you spend your euros.

After listening to too much sales talk and feeling even worse than when I first went into the pharmacy, I went to lift my spirits at my favorite and, I think, the most beautiful bridge in Paris, the bronze lamp-lined Pont Alexandre III. Its elaborate decorations include Art Nouveau lamps, cherubs, nymphs, and, at either end, gold winged horses valiantly prancing atop large cement pillars.

The metro is the best way to get to Montmartre but keep in mind that you have to climb 180 steps to get out from underground. This area attracts bohemians and artists (and tourists) and is very charming with its steep hills and narrow cobbled streets. At the top is Sacred Coeur, a basilica that looks like a big cream puff. On weekends, wine flows, scrumptious foods are available, musicians play, people dance, street artists draw, and the shops do a booming business.

The metro is the best way to get to Montmartre but keep in mind that you have to climb 180 steps to get out from underground. This area attracts bohemians and artists (and tourists) and is very charming with its steep hills and narrow cobbled streets. At the top is Sacred Coeur, a basilica that looks like a big cream puff. On weekends, wine flows, scrumptious foods are available, musicians play, people dance, street artists draw, and the shops do a booming business.

I have found the Parisians to be very polite, friendly and helpful. Whenever I needed help, I said “Bonjour, Madame/Monsieur. Parlez-vous Anglais?” And they always answered “just a leetle beet.” Then we proceeded en Anglais.

So my vacation at an end, I wrapped things up, packed my suitcase, and said a fond farewell to the nymphs in Luxembourg Gardens and the gargoyles on Eglise St. Sulpice. I thought about the homeless family who sleeps across the street and said a silent prayer for them as the bells of Eglise St. Germaine tolled.

Literary Paris: Private Book Lovers’ Tour

If You Go:

contact@apariscommechezsoi.com for apartment rental at 1 rue du Dragon, Paris.

La Coupole, 102 Boulevard du Montparnasse, 75014 Paris, France, tel. 33 1 43 20 14 20.

Ghosts of Paris: Private Evening Mystery Tour

About the author:

Elizabeth von Pier is a retired banker who has travelled extensively around the world. She typically travels with other women and brings that perspective to her writings. This, however, was her first solo trip. Ms. von Pier lives in Hingham, Massachusetts and has been published in TravelMag.co.uk and Journey Woman.

Photo credits:

Luxembourg Gardens by Jebulon / Public domain

Eglise Saint Sulpice by Mbzt / CC BY-SA

Notre Dame by Madhurantakam / CC BY-SA

Paris Metro station by DIMSFIKAS / CC BY-SA

History, as it’s studied in school, can be a tough concept to wrap your head around. Centuries can be covered in days; weeks can be spent on one event. For many, the time when prehistoric man was living and roaming the caverns and fields and mountains of the Earth gets scrambled with the era of the dinosaurs. I had a hard time figuring out a real timeline when I was in high school history class. In fact, it’s only been in living history, in exploring the places where these things actually took place, pressing my hand against the wall of a building that once witnessed a revolution, a king’s court dance, a meeting of the French Resistance, that I’ve been able to understand, even a little bit, the events, the moments, the people that came before me.

History, as it’s studied in school, can be a tough concept to wrap your head around. Centuries can be covered in days; weeks can be spent on one event. For many, the time when prehistoric man was living and roaming the caverns and fields and mountains of the Earth gets scrambled with the era of the dinosaurs. I had a hard time figuring out a real timeline when I was in high school history class. In fact, it’s only been in living history, in exploring the places where these things actually took place, pressing my hand against the wall of a building that once witnessed a revolution, a king’s court dance, a meeting of the French Resistance, that I’ve been able to understand, even a little bit, the events, the moments, the people that came before me. But somehow, prehistory is harder to get a grasp on. How can you look at a place and imagine nothing, none of the buildings or houses or even roads, none of the modernity that seems to exist wherever you go today? It’s difficult, near impossible, and yet I found it much easier to wrap my head around the prehistory as I journeyed through Southern France.

But somehow, prehistory is harder to get a grasp on. How can you look at a place and imagine nothing, none of the buildings or houses or even roads, none of the modernity that seems to exist wherever you go today? It’s difficult, near impossible, and yet I found it much easier to wrap my head around the prehistory as I journeyed through Southern France. Tautavel Man is a 450,000-year-old fossil, a proposed subspecies of Homo erectus, one of our true ancestors. I find it incredibly hard to fathom the time between when he was born and when I was, and yet that’s the point of the museum in the town of Tautavel, which explores the discoveries uncovered in the cave and offers a unique view of life in this region at Tautavel Man’s time.

Tautavel Man is a 450,000-year-old fossil, a proposed subspecies of Homo erectus, one of our true ancestors. I find it incredibly hard to fathom the time between when he was born and when I was, and yet that’s the point of the museum in the town of Tautavel, which explores the discoveries uncovered in the cave and offers a unique view of life in this region at Tautavel Man’s time.

The museum is split into two portions: the first is in the village and offers an exploration of the tools and shelters created by Tautavel man and his contemporaries. Visiting this portion of the museum first allows you to experience some of the wonder that the first archaeologists excavating in the cave above did.

The museum is split into two portions: the first is in the village and offers an exploration of the tools and shelters created by Tautavel man and his contemporaries. Visiting this portion of the museum first allows you to experience some of the wonder that the first archaeologists excavating in the cave above did. The museum is ideal for visits with kids, complete with activities in the summer including teaching participants how to throw a spear or make fire out of stones and moss. But even for adults, these activities are essential to gaining a true glimpse of life in the time of Tautavel Man.

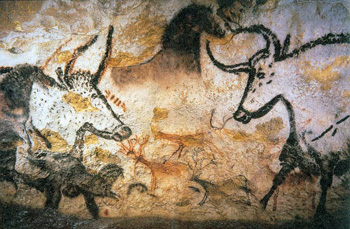

The museum is ideal for visits with kids, complete with activities in the summer including teaching participants how to throw a spear or make fire out of stones and moss. But even for adults, these activities are essential to gaining a true glimpse of life in the time of Tautavel Man. It is in Lascaux that, in 1940, three local teenagers accidentally stumbled upon prehistoric cave paintings, changing the way that we perceive of these “cave” men forever. Soon after their discovery, experts identified the paintings as Paleolithic art, some of the earliest to have ever been discovered. The paintings are far more recent than Tautavel man, at 17,300 years old, and they have long been a draw to this region, not far from Limoges, where art still remains an important element of local life due to the tradition of Limoges porcelain.

It is in Lascaux that, in 1940, three local teenagers accidentally stumbled upon prehistoric cave paintings, changing the way that we perceive of these “cave” men forever. Soon after their discovery, experts identified the paintings as Paleolithic art, some of the earliest to have ever been discovered. The paintings are far more recent than Tautavel man, at 17,300 years old, and they have long been a draw to this region, not far from Limoges, where art still remains an important element of local life due to the tradition of Limoges porcelain.

I went to Lascaux to visit the caves, but like all visitors since the 1960s, I actually visited Lascaux II, a replica of the original cave, which was closed when experts realized that lichen had become prevalent due to the frequency of visits and risked destroying the paintings. But visiting Lascaux II is not discouraging; after buying our tickets in the village of Montignac below and driving up to the caves, we are taken on a journey through time.

I went to Lascaux to visit the caves, but like all visitors since the 1960s, I actually visited Lascaux II, a replica of the original cave, which was closed when experts realized that lichen had become prevalent due to the frequency of visits and risked destroying the paintings. But visiting Lascaux II is not discouraging; after buying our tickets in the village of Montignac below and driving up to the caves, we are taken on a journey through time. The guide goes into details that never would have occurred to me over the next 45 minutes: how the paints were made by the artist, who shows considerable skill in representing the animals that existed around him including horses, cattle and stags. As we wander through the caves, I almost forget that this is a facsimile, until the guide explains the feat of reproducing the caves using a concrete base and the recreation of the same sorts of paints that would have been used for the originals. Lascaux II is accurate up to a couple of millimeters to the original.

The guide goes into details that never would have occurred to me over the next 45 minutes: how the paints were made by the artist, who shows considerable skill in representing the animals that existed around him including horses, cattle and stags. As we wander through the caves, I almost forget that this is a facsimile, until the guide explains the feat of reproducing the caves using a concrete base and the recreation of the same sorts of paints that would have been used for the originals. Lascaux II is accurate up to a couple of millimeters to the original.

As for the stage fright, it never goes away… it’s agony every single time but I stay focused and I know that once I’m on stage it’ll be fine; I’ll be in my happy little bubble.’

As for the stage fright, it never goes away… it’s agony every single time but I stay focused and I know that once I’m on stage it’ll be fine; I’ll be in my happy little bubble.’

Stockholm grew out of Stadsholmen, and the 13th century island was originally called Stockholm. As the city grew, it kept the Stockholm name, and the island became known as Staden Mellan Broarna: The Town Between the Bridges. It only became known as Gamla stan in the 20th century.

Stockholm grew out of Stadsholmen, and the 13th century island was originally called Stockholm. As the city grew, it kept the Stockholm name, and the island became known as Staden Mellan Broarna: The Town Between the Bridges. It only became known as Gamla stan in the 20th century. Stockholm means ‘log island’. The legend of Stockholm’s origins is that a log filled with gold was sent downstream from the old Swedish capital of Sigtuna, after they had trouble from armed gangs, and wherever that log landed would become their new capital.

Stockholm means ‘log island’. The legend of Stockholm’s origins is that a log filled with gold was sent downstream from the old Swedish capital of Sigtuna, after they had trouble from armed gangs, and wherever that log landed would become their new capital. Norway became independent of the Swedish kingdom in 1905. The Bernadotte dynasty still rules Sweden. Napoleon’s rule was ended at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Abba found fame singing Waterloo to win the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest for Sweden.

Norway became independent of the Swedish kingdom in 1905. The Bernadotte dynasty still rules Sweden. Napoleon’s rule was ended at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Abba found fame singing Waterloo to win the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest for Sweden. The bed wasn’t available until 2pm, so I walked around small Skeppsholmen island to Kungliga Djurgarden (The Royal Game Park) island, stopping along the way for a siesta under the sun in a small park.

The bed wasn’t available until 2pm, so I walked around small Skeppsholmen island to Kungliga Djurgarden (The Royal Game Park) island, stopping along the way for a siesta under the sun in a small park.

I had taken a ferry from Slussen, at the southern end of Skeppsbron, to the main island of four known as Fjaderholmarna. Opposite Djurgarden’s south-east tip we stopped under an impressive Carl Milles statue at Nacker. Fjaderholmarna was nice to walk around, with some pleasant coves, restaurants and craft shops. There were also lots of birds, primarily Canada geese and seagulls.

I had taken a ferry from Slussen, at the southern end of Skeppsbron, to the main island of four known as Fjaderholmarna. Opposite Djurgarden’s south-east tip we stopped under an impressive Carl Milles statue at Nacker. Fjaderholmarna was nice to walk around, with some pleasant coves, restaurants and craft shops. There were also lots of birds, primarily Canada geese and seagulls.

National Day

National Day

by Christine Sarikas

by Christine Sarikas  Years later, on the eve of my next trip to France, a friend I was meeting sent me an e-mail that contained three words: Château de Fontainebleau? Some quick research told me Fontainebleau was a palace used by French royalty, about 45 minutes from Paris. I was skeptical, feeling that visiting would mean long lines and vast car parks, but my friend insisted, so to Fontainebleau we went.

Years later, on the eve of my next trip to France, a friend I was meeting sent me an e-mail that contained three words: Château de Fontainebleau? Some quick research told me Fontainebleau was a palace used by French royalty, about 45 minutes from Paris. I was skeptical, feeling that visiting would mean long lines and vast car parks, but my friend insisted, so to Fontainebleau we went.

A château first stood on the site during the 12th century and served as a hunting lodge for the kings of France. In 1169, Thomas Becket, the exiled Archbishop of Canterbury, consecrated the site’s chapel to the Virgin Mary and Saint Saturnin. Numerous French kings visited and expanded the château, and in December of 1539, Fontainebleau, by then far larger and more luxurious than a simple hunting lodge, played host to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. His son, Henry II of France, was a frequent visitor, and Henry’s wife Catherine de Medici gave birth to six of their children within the château. Hunting parties continued to be held at Fontainebleau, marriages were arranged and conducted, a peace treaty between France and England was signed on 16 September 1629, and over a century later Louis XVI signed a trade agreement with England, effectively signaling the end of the American Revolutionary War. Monarchs, royals, and heads of state all visited the château, but Fontainebleau’s most famous resident did not arrive until 1803.

A château first stood on the site during the 12th century and served as a hunting lodge for the kings of France. In 1169, Thomas Becket, the exiled Archbishop of Canterbury, consecrated the site’s chapel to the Virgin Mary and Saint Saturnin. Numerous French kings visited and expanded the château, and in December of 1539, Fontainebleau, by then far larger and more luxurious than a simple hunting lodge, played host to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. His son, Henry II of France, was a frequent visitor, and Henry’s wife Catherine de Medici gave birth to six of their children within the château. Hunting parties continued to be held at Fontainebleau, marriages were arranged and conducted, a peace treaty between France and England was signed on 16 September 1629, and over a century later Louis XVI signed a trade agreement with England, effectively signaling the end of the American Revolutionary War. Monarchs, royals, and heads of state all visited the château, but Fontainebleau’s most famous resident did not arrive until 1803. Napoleon first visited the Château de Fontainebleau to inspect the newly finished military academy, École Spéciale Militaire. By the beginning of the 19th century, the château had fallen into disrepair; the vast majority of its furnishings had been sold during the French Revolution, and Fontainebleau was left empty and neglected. Napoleon chose to leave Versailles–with its Bourbon links–vacant and instead turned his attention to transforming Fontainebleau once again into a home and symbol of power.

Napoleon first visited the Château de Fontainebleau to inspect the newly finished military academy, École Spéciale Militaire. By the beginning of the 19th century, the château had fallen into disrepair; the vast majority of its furnishings had been sold during the French Revolution, and Fontainebleau was left empty and neglected. Napoleon chose to leave Versailles–with its Bourbon links–vacant and instead turned his attention to transforming Fontainebleau once again into a home and symbol of power.

Less widely known and visited than Versailles, Fontainebleau still offers the same degree of beauty and splendor. Its long history and renovations by generations of rulers has meant that Fontainebleau’s sprawling palace showcases examples of French architecture from the 12th to 19th centuries. Its most defining feature is its grand horseshoe staircase, commissioned by Louis XIII (who was born in the palace) and built by Jean Androuet du Cerceau. The majority of the château’s current buildings were constructed in the 14th century under Francis I, whose architect Gilles de Breton created much of the Cour Ovale, the château’s oldest and most central courtyard.

Less widely known and visited than Versailles, Fontainebleau still offers the same degree of beauty and splendor. Its long history and renovations by generations of rulers has meant that Fontainebleau’s sprawling palace showcases examples of French architecture from the 12th to 19th centuries. Its most defining feature is its grand horseshoe staircase, commissioned by Louis XIII (who was born in the palace) and built by Jean Androuet du Cerceau. The majority of the château’s current buildings were constructed in the 14th century under Francis I, whose architect Gilles de Breton created much of the Cour Ovale, the château’s oldest and most central courtyard. Fontainebleau, with its combination of Italian and French artistic styles, is considered by many to be the birthplace of the Renaissance within France. Much of the palace reflects the Italian Mannerist style, popular during the later years of the Renaissance and now widely known as the “Fontainebleau style.” The palace’s Gallery of Francis I, which is dominated by Florentine artist Rosso Fiorentino’s series of frescoes, was the first large decorated gallery to be created in France. Other Renaissance painters who contributed to the art at Fontainebleau include Francesco Primaticcio and Benvenuto Cellini; the latter’s Nymph of Fontainebleau is now housed at the Louvre.

Fontainebleau, with its combination of Italian and French artistic styles, is considered by many to be the birthplace of the Renaissance within France. Much of the palace reflects the Italian Mannerist style, popular during the later years of the Renaissance and now widely known as the “Fontainebleau style.” The palace’s Gallery of Francis I, which is dominated by Florentine artist Rosso Fiorentino’s series of frescoes, was the first large decorated gallery to be created in France. Other Renaissance painters who contributed to the art at Fontainebleau include Francesco Primaticcio and Benvenuto Cellini; the latter’s Nymph of Fontainebleau is now housed at the Louvre.