by Troy Herrick

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Renaissance Europe extended itself out into the New World in search of wealth and to spread Christianity. The Spanish employed a more direct approach through conquest, looting and the forcible conversion of the Aboriginal population of Central and South America to the Catholic Faith. The French, on the other hand, had a more peaceful and cooperative approach with their stone age contemporaries through trading posts and Christian missions. European manufactured goods were exchanged for the Indians’ animal pelts while Jesuit priests would spread Christianity and conversion was voluntary. Both cultures benefited, evolved and prospered.

The origins of Canada’s resource-based economy date back to the 17th century with the establishment of New France – a private colony run by a French fur trading company. Where is the best location for a trading post? The answer was obvious. Go where the Aboriginals gather or camp. It all began on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River at the site known as Tadoussac where the first in a string of trading posts and missions was established.

Tadoussac

Tadoussac has the distinction of being the oldest village in Canada as well as the oldest surviving French settlement in the Americas. Pierre de Chauvin, who was granted a fur trading monopoly by King Henry IV, chose this site for colonization and a small trading post in 1600 because it was already known to Basque and Norman whalers. Tadoussac was also a traditional Aboriginal site for barter. What better location for having the furs brought directly to you? There was also a safe bay for sheltering ships. All Chauvin had to do was supply the settlement with items for trade and colonists.

Unfortunately, what Chauvin overlooked was the rugged terrain, poor soil and cold winters in this region, all of which proved to be quite taxing. Only 5 of the original 16 ill-prepared colonists survived the first winter and that was only because of Aboriginal intervention with food, shelter and natural medications. This trading relationship flourished and by 1603 the French were welcomed by the people they had named Montagnais or “Mountain People” as permanent settlers and as allies.

During the height of the French Fur Trading Period, Tadoussac Bay was filled with trans-Atlantic sailing vessels. Even today it is not unusual to find tall ships arriving. On the day of our visit there was a lone two-masted ship anchored offshore and it was flying the Jolly Roger.

Feeling that we would not encounter any pirates today, we walked to the site of the oldest trading post in Canada. The present Chauvin Trading Post structure, dating to 1942, is a well-worn replica of the original. You find a steeply pitched red roof over rough cut wooden walls. The peeling white paint on the exterior walls betrays the age of the structure. This property is enclosed within a 4-foot high wooden fence made from 2 to 3-inch thick tree branches. Two wigwam frames and a life-sized wooden Indian carved from a tree trunk complete the décor.

Inside you find a stone fireplace in the centre of the room and a canoe suspended from the ceiling. French fur traders learned how to travel along the rivers and lakes of the new land from the Indians by means of such a canoe and it was their lifeline.

Displays include examples of typical European items for trade such as axes, knives, metal pots, blankets, coats and even milled flour. The French did not provide alcohol for trade. Other displays include samples of various pelts such as beaver, martin, wolf and bear. Beaver was the most highly-prized pelt because it was used for fashionable men’s hats in Europe at the time. The French developed a reputation for fair trade as they could not afford to risk losing their sole source of furs – their allies the Montagnais.

Jesuit missionaries later arrived to establish the first mission in 1640 and build upon the friendly relations between the French and the Montagnais. Their goal was to convert the Indians to Christianity.

A short walk down the street from the trading post, you find the Petite Chapelle de Tadoussac, the oldest wooden church in Canada. Dating to 1747, this church was associated with the early Jesuit Mission. Oriented toward the St. Lawrence River, the exterior of the church features white-washed walls and a bright red roof and steeple. Climb the 8 stone steps and enter the church. Inside you find a very basic, rough wooden interior with two rows of eight pews in the nave. The rectangular interior ends in a semi-circular chancel housing a white altar decorated with gold colored trim. Behind the altar is a sacristy. This church is known to house some of the original items used in the first mass celebrated here but I was not able to confirm this with anyone.

A short walk down the street from the trading post, you find the Petite Chapelle de Tadoussac, the oldest wooden church in Canada. Dating to 1747, this church was associated with the early Jesuit Mission. Oriented toward the St. Lawrence River, the exterior of the church features white-washed walls and a bright red roof and steeple. Climb the 8 stone steps and enter the church. Inside you find a very basic, rough wooden interior with two rows of eight pews in the nave. The rectangular interior ends in a semi-circular chancel housing a white altar decorated with gold colored trim. Behind the altar is a sacristy. This church is known to house some of the original items used in the first mass celebrated here but I was not able to confirm this with anyone.

Over time, local fur resources were depleted which necessitated traders to extend their reach out further by means of more distant trading posts such as those at Chicoutimi and Metabetchouane to the northwest. This was facilitated by the coureurs des bois (runners of the woods). Qualifications for such a position included a willingness to go native, paddling a canoe for up to 18 hours a day and capable of carrying at least two 90-pound bundles of furs at a time over a portage. Some portages were as long as 6 miles. Such a harsh lifestyle was not financially conducive to a comfortable and early retirement. Hernias and other serious injuries were common.

The coureurs des bois traveled up the Saguenay Fjord to Chicoutimi by water. Diane and I had a car and we did not have to lug heavy packs around portages. This allowed us to appreciate the beauty of the deeply chiseled Laurentian Mountains and the fjord, both having been carved out over successive ice ages. Steep rock faces ran along the river and heights of more than 450-feet were not uncommon along the way to Chicoutimi.

The coureurs des bois traveled up the Saguenay Fjord to Chicoutimi by water. Diane and I had a car and we did not have to lug heavy packs around portages. This allowed us to appreciate the beauty of the deeply chiseled Laurentian Mountains and the fjord, both having been carved out over successive ice ages. Steep rock faces ran along the river and heights of more than 450-feet were not uncommon along the way to Chicoutimi.

Chicoutimi

The Chicoutimi Trading Post and Jesuit Mission were established as early as 1676 on the site of an earlier Aboriginal settlement. At its peak, there were as many as 10 buildings including a chapel, store, clerk’s house and lodging for a Jesuit missionary. All good things must come to an end and this trading post was closed in 1856. The site continued to host a functioning chapel until 1930 when it too was demolished. Now all that remains is a marker to commemorate the trading post. With this we drove on to Metabetchouane Trading Post at Des Biens.

Des Biens

The Montagnais would tell horror stories to the French about scary monsters and dangers lurking in the Lac St. Jean in order to keep them out of the region filled with rich fur resources. This changed in 1647 when Jesuit missionary Jean de Quen was guided into the Des Bien area to assist with treating a large number of ill people. At the time, De Quen made no mention of the Metabetchouane River entering the lake at this location but he did not leave without establishing a church in the vicinity.

The accessibility of this location was not apparent until a second Jesuit, Charles Albanel, returned to attend a meeting of twenty Indian nations in 1671. Five years later the St. Charles Mission and the Metabetchouane Trading Post were operating at the mouth of the river on the site of a traditional Indian camp. Now exchanging goods was more convenient for both parties.

The Metabetchouane Centre of History and Archeology and Metabetchouane Trading Post details this period in history. A chart on the wall outlines the value of each European item in terms of beaver pelts. Items sought by the Montagnais had to be portable because of their nomadic lifestyle and had to improve their living conditions in such a harsh environment. These included rifles, powder horns, axes, scythes, hand drills, tin cups, metal pots, blankets, clothing and sail canvas which replaced animal skins on wigwams and long houses. Samples of these are displayed on the rough cut wooden walls inside the centre.

Cultural exchanges were also both desirable and inevitable as the coureurs des bois would winter with the Indians to ensure their own survival. They learned to construct birch bark canoes, toboggans and snowshoes. They lived off the land and survived on native foods that were unknown in Europe at the time like pumpkin, artichokes, maple syrup and moose and beaver meat.

Outside on the grounds is a reproduction of a small church. The original 1849 structure was built by the Hudson Bay Company on the site of Jean de Quen’s original church. A steeple with a cross crowns the rough-cut gray plank walls below. Just to the left of the church is a stone memorial dedicated to De Quen.

The grounds also contain a small powder magazine built some time before 1778. Look for the stone structure with gray wooden shingles and wooden door. Nearby is an A-frame roof covering a dome-shaped stone oven with two cast iron doors. A wigwam covered with sail canvas is also on site.

After touring the grounds, walk or drive through the narrow underpass down towards the water. Near the white gazebo, you find yourself standing on the site of the Hudson’s Bay Trading Post. The French trading post was situated opposite this spot on the other side of the river. We were unable to reach this site as we would have had to pass over private property. The French abandoned the Metabetchouane Trading Post in 1696 but the Hudson’s Bay Company resurrected it between 1768 to 1880 before finally closing it and moving to nearby Mashteuiatsh.

Mashteuiatsh

Present-day Mashteuiatsh, a First Nations Reservation on the shore of Lac St. Jean, is where you can learn about the Montagnais Culture as taught by the Montagnais themselves. While the French had named them Montagnais, they call themselves Pekuakamiulnuatsh or the People of the Shallow or Flat Lake because Lac St. Jean is only about ten feet deep at most.

The museum reflects the nomadic ways of the Pekuakamiulnuatsh and how their lives changed with the seasons. They collected berries in the summer, hunted moose in the fall and fished and trapped animals in the winter. Displays include the various tools used for survival.

A very informative audio helps to put their lifestyle into perspective and how they lived off the land. They transported their worldly goods by toboggan, hunted moose using rifles and fished with the aid of nets. They also assembled V-shaped hunting tents capable of sheltering up to 8 individuals. A portable wood burning stove, obtained by means of trading, provided warmth on those cold winter nights.

Outside on the grounds you can stroll through a forest interpretation trail known as the Nutshimatsh. Here you find local plants, trees and shrubs that were used for shelter, travel (toboggans and snowshoes), food (blueberries, wild cherries, raspberries) and medicines. I felt a sense of peace and tranquility come over me as I walked along these pathways.

Finally, this is the only place where you will find a wooden framed longhouse (shaputuan) that is capable of housing as many as 10 or 12 families wishing to settle in one location for a longer period of time. The shaputuan was approximately 36 feet long and 18 feet wide with a 12-foot high arched sail canvas roof. Warmth was provided during the winter by placing pine branches on the ground in addition to the portable wood burning stove with a chimney extending through the roof.

Continue your visit at the nearby Uashassihtsh Cultural Centre where you see traditional Pekuakamiulnuatsh craftspeople at work. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh were dependant upon the birch bark canoe for their survival and they viewed it as both living and as a source of life. At the cultural centre, they construct birch bark canoes using traditional methods. Two people can construct a canoe in two weeks using an axe or a crooked knife and a few other tools. The final product weighs about 85 lbs and is light enough for two people to carry it over a portage.

Our guide showed us a 20-inch diameter tambourine-like drum fashioned using a leather hide stretched over a circular wooden frame. She indicated that such a drum was a traditional hunting tool. While my first thought was that it would more likely scare the animals away, I could not have been more wrong. The elders would beat this drum and enter a trance-like state. Upon awakening they reported where the best hunting grounds were to be found.

Our guide showed us a 20-inch diameter tambourine-like drum fashioned using a leather hide stretched over a circular wooden frame. She indicated that such a drum was a traditional hunting tool. While my first thought was that it would more likely scare the animals away, I could not have been more wrong. The elders would beat this drum and enter a trance-like state. Upon awakening they reported where the best hunting grounds were to be found.

The Pekuakamiulnuatsh hunted animals of all sizes and then processed the hides into leather. These were tied to and stretched out on wooden frames followed by softening them with bear fat, scraping them using caribou bone tools and finally preserving them using the smoke from an open fire in order to kill the bacteria. The leather was then used for clothing, gloves, moccasins and snowshoes.

Snowshoes were woven from strips of moose leather. An expert craftsman such as the one on site usually requires at least a day to weave a single snowshoe. At the time of our arrival he had just completed a snowshoe whose shape was somewhat reminiscent of a tennis racket at 3 feet long and approximately 20 inches wide, although styles and shapes do vary.

Meat and fish were preserved by being placed on the shelves of an almost conical wooden drying rack whose base was approximately 5-feet in diameter. Bannock, a traditional corn bread, was also available for tasting. I found the taste to be slightly reminiscent to that of regular white bread.

The final stop at the cultural centre was the general store where shelves were stocked with European goods including shortening, lard, baking powder, tea, oil lamps, china plates, cups, hats, clothing and blankets. You also find a number of animal pelts on the counter – beaver, lynx, otter, bear, wolf – suggesting that this was more than just a general store; it was also a trading post. This would appear to be a reproduction of the Hudson’s Bay Trading Post that was moved to Mashteuiatsh from Metabetchouane. I could not confirm that this was the original site of that trading post however.

The final stop at the cultural centre was the general store where shelves were stocked with European goods including shortening, lard, baking powder, tea, oil lamps, china plates, cups, hats, clothing and blankets. You also find a number of animal pelts on the counter – beaver, lynx, otter, bear, wolf – suggesting that this was more than just a general store; it was also a trading post. This would appear to be a reproduction of the Hudson’s Bay Trading Post that was moved to Mashteuiatsh from Metabetchouane. I could not confirm that this was the original site of that trading post however.

Upon exiting the Uashassihtsh Cultural Centre, it is a short drive over to the Church of St. Kateri Tekakwitha. This very modern-looking church is dedicated to the first and only Aboriginal Saint to date. While there has been a church present on site since 1896, this one dates to 1987 and has a First Nations interior décor. The apse features a large crucifix hanging behind the altar flanked by a snowshoe on each side. The hand-carved statues of Mary and Joseph both have a natural wood finish, as does the wooden altar. The Chapel of St. Kateri on the right side of the nave houses her relic, a bone fragment taken from her lower sternum.

After leaving the church, I had a better appreciation for the relationship between the French and the Pekuakamiulnuatsh over the course of history. The French first came into contact with a stone age people yet they would not have survived in this harsh new environment without their assistance. At the same time, the lifestyle of the Pekuakamiulnuatsh was clearly improved through trade with the French. This may in fact be the only true example of peaceful co-existence in the New World where both parties benefited from associating with the other as opposed to being at odds.

If You Go:

Tadoussac is situated on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, 134 miles east of Quebec City.

The Chauvin Trading Post (Poste de Traite Chauvin) is located at 157, rue Bord De L’Eau, just above Tadoussac Bay. Admission is $5.

The Chapelle de Tadoussac is located at rue du Bord-de-l’Eau C.P. 219, just down the street from the Chauvin Trading Post. Admission is free.

Chicoutimi is located on the Saguenay River, 78 miles from Tadoussac.

The Chicoutimi Trading Post site was located in the wooded area between boulevard du Saguenay and rue Price.

Des Biens is on the south shore of Lac St. Jean, 46.8 miles west of Chicoutimi.

The Metabetchouane Centre of History and Archeology and Metabetchouane Trading Post (Centre D’Histoire et D’Archeologie del al Metabetchouane and Poste De Trait Metabetchouane) is located at 243 rue Hébert. Admission is $8.

Mashteuiatsh is approximately 20.8 miles west from Des Biens.

The Native Museum of Mashteuiatsh is located at 1787 Rue Amishk in Mashteuiatsh. Admission is $12.

The Uashassihtsh Cultural Centre (Site de Transmission Culturelle – Uashassihtsh) is located at 1514 Rue Ouiatchouan in Mashteuiatsh. Admission is $15.

The Church of St. Kateri Tekakwitha is located at 1787 Rue Amishk in Mashteuiatsh. Admission is free.

About the author:

Troy Herrick, a freelance travel writer, has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. His articles have appeared in Live Life Travel, International Living, Offbeat Travel and Travels Thru History Magazines

Photographs:

Diane Gagnon, a freelance photographer, has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. Her photographs have accompanied Troy Herrick’s articles in Live Life Travel, Offbeat Travel and Travels Thru History Magazines.

.

This “Grand Lady of the Sea” is also reputed to be the setting of one of the most famous love stories of our time. It’s widely reported that Wallis Simpson, married to a U.S. naval officer at the time and living in Coronado, met her future husband at a grand banquet at the hotel in 1920, thereby changing the course of history.

This “Grand Lady of the Sea” is also reputed to be the setting of one of the most famous love stories of our time. It’s widely reported that Wallis Simpson, married to a U.S. naval officer at the time and living in Coronado, met her future husband at a grand banquet at the hotel in 1920, thereby changing the course of history.

From the ground level, you can climb up the set of stairs to the balcony level, where you are able to stand next to the Lincoln Box. (The interior of the Box is closed to the public to protect it from damage).

From the ground level, you can climb up the set of stairs to the balcony level, where you are able to stand next to the Lincoln Box. (The interior of the Box is closed to the public to protect it from damage).

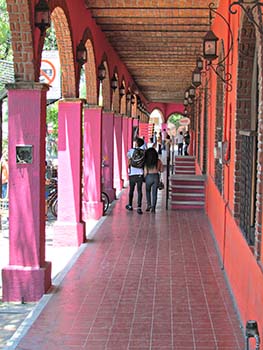

While in Ajijic I visited Tlaquepacque. I thought it would be “touristy” but I was wrong. The scores of local people experiencing the magic Tlaquepacque offers, put that myth to rest.

While in Ajijic I visited Tlaquepacque. I thought it would be “touristy” but I was wrong. The scores of local people experiencing the magic Tlaquepacque offers, put that myth to rest.

The Jardin Hidalgo filled with laughter, music, chirping birds, and happy people is the heart of Tlaquepacque. Its melodious fountains, numerous flower beds and shady trees, provides a visually stunning space for those seeking to get away from the crowded avenues. The colorful bandstand draws those who are seeking shade on a sizzling sunny day. Surrounded by Tlaquepacque’s two churches, you are sure to hear the ringing of church bells. Take time to walk around the square, you will not be disappointed.

The Jardin Hidalgo filled with laughter, music, chirping birds, and happy people is the heart of Tlaquepacque. Its melodious fountains, numerous flower beds and shady trees, provides a visually stunning space for those seeking to get away from the crowded avenues. The colorful bandstand draws those who are seeking shade on a sizzling sunny day. Surrounded by Tlaquepacque’s two churches, you are sure to hear the ringing of church bells. Take time to walk around the square, you will not be disappointed. While there are many shops to tempt you with handmade items, interesting items for sale can be found if you just look down. While walking in front of the Santuario de Nuestra Senora de la Soledad Church (behind the Jardin Hildalgo), I spotted this artisan creating crucifixes out of palm fronds. Her hands were magical. I was captivated by the speed with which she fashioned a frond into a crucifix. There are many artisans like this scattered around town, just keep your eyes open and you are bound to find a special souvenir.

While there are many shops to tempt you with handmade items, interesting items for sale can be found if you just look down. While walking in front of the Santuario de Nuestra Senora de la Soledad Church (behind the Jardin Hildalgo), I spotted this artisan creating crucifixes out of palm fronds. Her hands were magical. I was captivated by the speed with which she fashioned a frond into a crucifix. There are many artisans like this scattered around town, just keep your eyes open and you are bound to find a special souvenir. Amazing sculptures are scattered throughout Tlaquepacque. They run the gamut from life like to surreal. What they have in common is detail, exquisite detail. My favorite is by Sergio Bustamante. Born in Mexico, he is an artist who has worked in all mediums but is best known for his sculptures. As I stood in front of this sculpture, a gentleman shared that Bustamante was fascinated by the thought of children flying and often had dreams of flying as a child. This sculpture, according to him, was based on that theme.

Amazing sculptures are scattered throughout Tlaquepacque. They run the gamut from life like to surreal. What they have in common is detail, exquisite detail. My favorite is by Sergio Bustamante. Born in Mexico, he is an artist who has worked in all mediums but is best known for his sculptures. As I stood in front of this sculpture, a gentleman shared that Bustamante was fascinated by the thought of children flying and often had dreams of flying as a child. This sculpture, according to him, was based on that theme. Bustamante has a gallery on Calle Independencia. I walked inside hoping to find out more about the flying theme. It was a weekend and they were busy. The next visit will be mid week…I am planning on having my questions answered.

Bustamante has a gallery on Calle Independencia. I walked inside hoping to find out more about the flying theme. It was a weekend and they were busy. The next visit will be mid week…I am planning on having my questions answered.

The exhibit is a model lover’s nirvana, thousands and thousands of soldiers, sailors, pilots, planes, ships, rockets, hangars, bridges, mountains, trees and much more. Steve has re-created all the European battles in WWII. Each scene is historically correct and to scale. Detailed reader’s panels describe the dioramas.

The exhibit is a model lover’s nirvana, thousands and thousands of soldiers, sailors, pilots, planes, ships, rockets, hangars, bridges, mountains, trees and much more. Steve has re-created all the European battles in WWII. Each scene is historically correct and to scale. Detailed reader’s panels describe the dioramas. Steve started his hobby at age nine, inspired by WWII movies and books. He learned to make models, then moved on to assembling historically correct and scaled dioramas. His collection grew until his teen years when, as he says, “I took on other interest.” Some years passed until he was motivated to begin his modeling hobby again. His own son was the inspiration. They worked together until, you guessed it, his son became a teenager. Today Steve lives in Salem and is a plant facility manager.

Steve started his hobby at age nine, inspired by WWII movies and books. He learned to make models, then moved on to assembling historically correct and scaled dioramas. His collection grew until his teen years when, as he says, “I took on other interest.” Some years passed until he was motivated to begin his modeling hobby again. His own son was the inspiration. They worked together until, you guessed it, his son became a teenager. Today Steve lives in Salem and is a plant facility manager.

Cavernous doesn’t begin to describe Hangar B. Standing in the middle, you’re dwarfed. I think I know how ants feel encountering humans. Today hangar B houses vintage aircraft and a museum dedicated to the WWII activities that took place there.

Cavernous doesn’t begin to describe Hangar B. Standing in the middle, you’re dwarfed. I think I know how ants feel encountering humans. Today hangar B houses vintage aircraft and a museum dedicated to the WWII activities that took place there.

Blue Heron French Cheese Company

Blue Heron French Cheese Company