New Orleans, Louisiana

by Troy Herrick

The lifeblood of New Orleans is Mardi Gras, jazz, jambalaya and gumbo but “The City That Care Forgot” also has a spiritual side to it – voodoo. This religion was first brought to the Big Easy between 1806 and 1810 when slave ships were re-routed from Santo Domingo (present day Dominican Republic) to New Orleans during the Servile Wars. To their surprise the new slaves found that New Orleans had only one legally sanctioned religion which was Roman Catholicism. Furthermore the Code Noir, introduced by the French Government in 1724, required that all slaves be baptised Catholics. How did the newcomers solve this dilemma? They adapted their own religion to that of the Catholic Church by matching voodoo spirits (loas) to the various saints. Technically this meant that only Catholics could practice voodoo in New Orleans.

Our curiosity piqued as we entered the New Orleans Voodoo Museum to purchase tickets for the voodoo walking tour of the French Quarter. Our senses were challenged by the smell of incense and the sound of eerie music saturating the air as we visited the supernatural displays. The bizarre voodoo paraphernalia included several altars topped with offerings of paper money, coins, tobacco products and alcohol and a large orange and white snake used in some rituals.

Statues of saints seemed more out of place than the skeletons because this was no church. Then there were the voodoo dolls. Voodoo practitioners believe that voodoo dolls don’t just represent someone but actually become that person when a personal item such as a lock of hair or fingernails is added.

Statues of saints seemed more out of place than the skeletons because this was no church. Then there were the voodoo dolls. Voodoo practitioners believe that voodoo dolls don’t just represent someone but actually become that person when a personal item such as a lock of hair or fingernails is added.

A sketch of a zombie conjured up an image of a hoard of zombies whose decaying corpses creep around in the misty dark of night seeking to devour the brains of the living. “Hold on there before your imagination gets carried away” said our tour guide NU’awlons Natescott. “There were no zombies in New Orleans. If you want to find a zombie in New Orleans you should go to the nearest bar and buy the drink.” He said that 70% of the things you hear about voodoo is actually hoodoo (a con game). What people think they know about zombies is the result of what hoodoo has portrayed them. He also indicated that a real zombie (those found in Haiti) might eat your brain but only if it was cooked.

Our education continued when our tour guide reported that New Orleans voodoo is synonymous with voodoo queen Marie Laveau (1793-1882), whom he referred to as a free woman of color. NU’awlons pointed up at her picture on the wall as we left the museum to begin the walking tour. She was at the height of her power/influence in the 1850s. Although she was not psychic she had built up that reputation by collecting gossip when she visited various houses in the French Quarter to braid women’s hair.

Our education continued when our tour guide reported that New Orleans voodoo is synonymous with voodoo queen Marie Laveau (1793-1882), whom he referred to as a free woman of color. NU’awlons pointed up at her picture on the wall as we left the museum to begin the walking tour. She was at the height of her power/influence in the 1850s. Although she was not psychic she had built up that reputation by collecting gossip when she visited various houses in the French Quarter to braid women’s hair.

At the age of thirteen, Marie had a daughter named Marie Eloise who looked so much like her as she grew older that people could not tell them apart. This created the impression that the elder Marie could be in two places at the same time. Marie Eloise would eventually succeed her mother as the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans.

Our first stop was the St. Louis Cathedral but not to visit the interior. Instead we walked outside to the rear of the building where we found a small garden fenced off from the public. Peering through the wrought iron fence we saw a statue of Christ with raised arms. Marie Laveau was a member of this church congregation and she was known to perform voodoo rituals in this garden.

Our first stop was the St. Louis Cathedral but not to visit the interior. Instead we walked outside to the rear of the building where we found a small garden fenced off from the public. Peering through the wrought iron fence we saw a statue of Christ with raised arms. Marie Laveau was a member of this church congregation and she was known to perform voodoo rituals in this garden.

We then crossed the French Quarter to the former site of Marie Laveau’s home. Her house was torn down in 1903 and replaced by the present structure. Marie was known to have performed voodoo rituals in the back yard but we were not able to view this area.

We crossed Basin Street and entered the neighborhood of Treme to visit Congo Square in Louis Armstrong Park. Creole slave owners strictly enforced the practice of Catholicism but the slaves circumvented this by gathering at Congo Square each Sunday (their one day off during the week under the Code Noire) to sing and gyrate to the rhythm of drum beats. They also participated in voodoo rituals.

We crossed Basin Street and entered the neighborhood of Treme to visit Congo Square in Louis Armstrong Park. Creole slave owners strictly enforced the practice of Catholicism but the slaves circumvented this by gathering at Congo Square each Sunday (their one day off during the week under the Code Noire) to sing and gyrate to the rhythm of drum beats. They also participated in voodoo rituals.

Inside the park we found ourselves surrounded by shady and gnarled oak trees. Coincidentally we could hear drum beats in the background but were never able to locate the source of the drumming. Looking down we found ourselves standing on a number of spiral-like patterns constructed from inlaid bricks. With a little imagination you could almost see a group of people dancing on top of these designs.

After you find your inner beat, leave Congo Square and visit the nearby Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel. This church boasts a number of local voodoo practitioners among its congregation but you likely will not be able to identify them because they look just like anybody else.

After you find your inner beat, leave Congo Square and visit the nearby Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel. This church boasts a number of local voodoo practitioners among its congregation but you likely will not be able to identify them because they look just like anybody else.

Just inside the front door of the chapel on your right you find a statue of a Roman soldier holding a crucifix. This statue was originally found inside a crate labelled with the word “Expedite.” Since no one could identify who this statue represented he became known as St. Expedite. The Catholic Church has never canonized any saint bearing the name of Expedite so this statue had no one praying to him for his intercession. Slaves at that time adopted him and he has been worshipped by voodoo practitioners and local Catholics ever since.

Exit the Chapel and proceed to St. Louis Cemetery #1. The living is admitted free but the families of the dead must pay to maintain the upkeep of all the above-ground tombs that surround you. The French had a custom of interring people above ground because they did not want to have buried coffins rising to the surface and falling open because of the high water table and flooding for which the Crescent City is famous. With a little imagination you have the making of a good horror movie where the zombies rise from the open coffins in search of the living.

Exit the Chapel and proceed to St. Louis Cemetery #1. The living is admitted free but the families of the dead must pay to maintain the upkeep of all the above-ground tombs that surround you. The French had a custom of interring people above ground because they did not want to have buried coffins rising to the surface and falling open because of the high water table and flooding for which the Crescent City is famous. With a little imagination you have the making of a good horror movie where the zombies rise from the open coffins in search of the living.

Your mission, if you choose to proceed inside the city of the dead, is to find the tomb of Marie Laveau. Look for a dilapidated red/brown brick structure covered with many sets of three handwritten Xs on its surface. You many also find coin offerings left by visitors in the hope that Marie Laveau will grant their wishes.

People often confuse Marie Eloise’s tomb with that of her more famous mother. In fact, for this reason, Marie Eloise’s tomb is the second most frequently visited grave in the U.S. behind that of Elvis. If you are able to locate this structure you will find that it is in better condition than that of the elder Marie.

Our tour ended at this site. After wandering around in search of the exit, we took the opportunity to find a Zombie but since we had stopped at Pat O’Brien’s we had to settle for a Hurricane instead, something else that New Orleans is famous for.

Historic Voodoo and Cemetery Tour in New Orleans

If You Go:

♦ The New Orleans Voodoo Museum is located at 724 Dumaine St. You can purchase your Voodoo Tour ticket here. It was $19 at the time of my visit and includes admission to the museum.

♦ St. Louis Cathedral is located at Jackson Square.

♦ The former site of Marie Laveau’s home is 1020-22 St. Ann Street

♦ Congo Square is situated in Louis Armstrong Park which is located at 835 N. Rampart St. Admission is free.

♦Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel is located at 411 N. Rampart St.

♦ St. Louis Cemetery #1 is located at Basin and Conti Streets. To find Marie Laveau’s tomb enter from Basin Street and proceed to the side wall on your far left and then turn right. You pass three tombs on your right before you see that of Marie Laveau. Do not visit the cemetery after dark as people have been attacked here (by the living).

♦ If you wander around a little in the area between the elder Marie’s tomb and the Basin Street entrance you might find a small aluminum disc on the ground with the #3 on it. You will know that Marie Eloise’s tomb is nearby when you find it this disc. Look for the sets of triple Xs on the whitewashed tomb.

♦ Pat O’Brien’s is located at 718 St. Peter St.

♦ If you wish to purchase that perfect voodoo souvenir, there are number of voodoo shops located around the French Quarter. Just take a leisurely stroll and you are sure to pass by one. Just look for names like Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo and Reverend Zombie’s House of Voodoo. Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo is located at 739 Bourbon St. Reverend Zombie’s House of Voodoo is located at 723 St. Peter St.

About the author:

Troy Herrick, a freelance travel writer, has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. His articles have appeared in Live Life Travel, International Living, Offbeat Travel and Travel Thru History Magazines.

All photos by Diane Gagnon, a freelance photographer who has traveled extensively in North America, the Caribbean, Europe and parts of South America. Her photographs have accompanied Troy Herrick’s articles in Live Life Travel, Offbeat Travel and Travel Thru History Magazines:

New Orleans Voodoo Museum

St. Expedite

Portrait of Marie Laveau

Yard behind the St. Louis Cathedral

Congo Square

Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel

Tour guide by Marie Laveau’s tomb

Walking through each room of Clark’s Tin Shop, I was able to take all the time I wanted, looking at many historic items and reading through so much fascinating information about the people and clandestine movement of the time.

Walking through each room of Clark’s Tin Shop, I was able to take all the time I wanted, looking at many historic items and reading through so much fascinating information about the people and clandestine movement of the time.

Starr Clark and his wife offered a temporary haven to fugitive slaves, in the attic of their home. They gave families, desperate for freedom, directions and solid contacts to the lake ports of Oswego, Cape Vincent, Port Ontario and Sackets Harbor. Once there, each could secure passage to Canada and a new life.

Starr Clark and his wife offered a temporary haven to fugitive slaves, in the attic of their home. They gave families, desperate for freedom, directions and solid contacts to the lake ports of Oswego, Cape Vincent, Port Ontario and Sackets Harbor. Once there, each could secure passage to Canada and a new life. The gentleman was writing the United Herald newspaper, letting the editor know how two fugitive slaves, Williams and Scott, had made their way to the safety of Canada, thanks, in part, to Starr Clark.

The gentleman was writing the United Herald newspaper, letting the editor know how two fugitive slaves, Williams and Scott, had made their way to the safety of Canada, thanks, in part, to Starr Clark. The tin shop today is set up to show how things were way-back-when. A good tinsmith could fashion a tin pan in less than 20 minutes.

The tin shop today is set up to show how things were way-back-when. A good tinsmith could fashion a tin pan in less than 20 minutes.

Usually in such a place, you may only view rooms from a doorway and snap a photo, so imagine my delight to find that for the same price as the Best Western a few blocks away, you can spend the night in this piece of living history.

Usually in such a place, you may only view rooms from a doorway and snap a photo, so imagine my delight to find that for the same price as the Best Western a few blocks away, you can spend the night in this piece of living history. Mr. Bandini was known for both his huge parties, and his political involvement. Guests travelled long distances to attend his famous 3 day fandangos involving food, drinks, music and a favorite of Mr. Bandini’s, dancing. Though known as a gracious host, it was not all fun and games for Juan Bandini. Many important political meetings that shaped the history of California were held right here in the salon. Here, along with other prominent Californios, Bandini planned revolts against more than one Mexican ruler of the day. During the Mexican-American war Juan Bandini was an American supporter and this home was the headquarters for Commodore Stockton. It was here that scout Kit Carson was sent by General Kearny to request aid in the battle of San Pasqual.

Mr. Bandini was known for both his huge parties, and his political involvement. Guests travelled long distances to attend his famous 3 day fandangos involving food, drinks, music and a favorite of Mr. Bandini’s, dancing. Though known as a gracious host, it was not all fun and games for Juan Bandini. Many important political meetings that shaped the history of California were held right here in the salon. Here, along with other prominent Californios, Bandini planned revolts against more than one Mexican ruler of the day. During the Mexican-American war Juan Bandini was an American supporter and this home was the headquarters for Commodore Stockton. It was here that scout Kit Carson was sent by General Kearny to request aid in the battle of San Pasqual.

Heading upstairs and walking along the expansive 2nd story veranda overlooking San Diego’s old town, it’s easy to daydream about what life might have been like in the hotels’ heyday. Close your eyes as the dry dust rises in small clouds from the dirt streets below. Listen for the clatter of the horses pulling the stagecoach up in front of the hotel to unload passengers, weary from the 35 hour passage from Los Angeles. Imagine the laughter of the saloon crowd, the bustle of the town, and the rustle of crinolines as women pass on their way to the haberdashery.

Heading upstairs and walking along the expansive 2nd story veranda overlooking San Diego’s old town, it’s easy to daydream about what life might have been like in the hotels’ heyday. Close your eyes as the dry dust rises in small clouds from the dirt streets below. Listen for the clatter of the horses pulling the stagecoach up in front of the hotel to unload passengers, weary from the 35 hour passage from Los Angeles. Imagine the laughter of the saloon crowd, the bustle of the town, and the rustle of crinolines as women pass on their way to the haberdashery. Opening the faux finished door from the veranda reveals a room filled with period furnishings. A globe shaped lamp, fashioned after the old kerosene style, sits on the table beside the dark, ornately carved bed. Wallpaper, in vintage patterns of leaves and vines form a backdrop for the thick red velvet curtains trimmed with large gold tassels. Double hung, wood framed windows on either side of the door look out onto the veranda and the town below. Each room has its own characters and features, like fireplaces or sitting rooms, though you will not find a TV in the room to distract from the authenticity of the place. The comfy cotton quilt seems like a perfect place to curl up with a book.

Opening the faux finished door from the veranda reveals a room filled with period furnishings. A globe shaped lamp, fashioned after the old kerosene style, sits on the table beside the dark, ornately carved bed. Wallpaper, in vintage patterns of leaves and vines form a backdrop for the thick red velvet curtains trimmed with large gold tassels. Double hung, wood framed windows on either side of the door look out onto the veranda and the town below. Each room has its own characters and features, like fireplaces or sitting rooms, though you will not find a TV in the room to distract from the authenticity of the place. The comfy cotton quilt seems like a perfect place to curl up with a book. When Seeley built his grand stagecoach hotel with 20 guestrooms in 1869, it may surprise you to learn that it did not include indoor plumbing. Chamber pots and outhouses were the facilities of the day. Indoor plumbing was not added until 1930. Don’t worry though, although the 2010 restoration, overseen by teams of experts and historians, included the use of as much of the original materials as possible, the bathrooms are not original. The 20 rooms were converted into 10 unique guestrooms, accommodating guest bathrooms that include pull chain toilets, pedestal sinks, modern rain head showers and in some cases antique copper or wooden soaker tubs. It still has that 1880s feeling but with all the modern conveniences.

When Seeley built his grand stagecoach hotel with 20 guestrooms in 1869, it may surprise you to learn that it did not include indoor plumbing. Chamber pots and outhouses were the facilities of the day. Indoor plumbing was not added until 1930. Don’t worry though, although the 2010 restoration, overseen by teams of experts and historians, included the use of as much of the original materials as possible, the bathrooms are not original. The 20 rooms were converted into 10 unique guestrooms, accommodating guest bathrooms that include pull chain toilets, pedestal sinks, modern rain head showers and in some cases antique copper or wooden soaker tubs. It still has that 1880s feeling but with all the modern conveniences. Leaving the hotel to explore, you are just steps from museums, interpretative displays artisans, shops, restaurants, and a theater. When night falls and the park closes, you are left with unique access to Old Town, to quietly contemplate what it was like for those early settlers of the Wild West.

Leaving the hotel to explore, you are just steps from museums, interpretative displays artisans, shops, restaurants, and a theater. When night falls and the park closes, you are left with unique access to Old Town, to quietly contemplate what it was like for those early settlers of the Wild West.

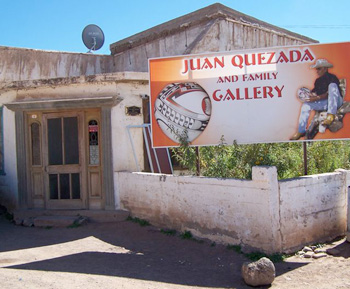

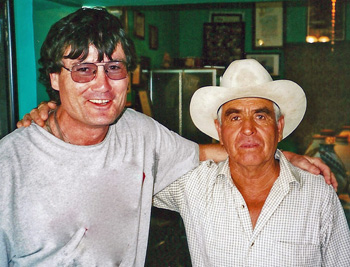

Quezada’s modest gallery is on the corner of the main street across from the historic, refurbished railroad line. As I enter, the artist, now in his early seventies, breezes in from the side room. Dressed in a faded tan cowboy hat, trim, medium height, bantamweight, looking fit as an Oklahoma rodeo wrangler, he welcomes me: “Buenas tardes, señor. Mi casa es su casa,” His rugged, suntanned face exudes a quiet humility and keen curiosity shaped by his many years of desert life. Later, he puts his arm around me, and Dick snaps my photo.

Quezada’s modest gallery is on the corner of the main street across from the historic, refurbished railroad line. As I enter, the artist, now in his early seventies, breezes in from the side room. Dressed in a faded tan cowboy hat, trim, medium height, bantamweight, looking fit as an Oklahoma rodeo wrangler, he welcomes me: “Buenas tardes, señor. Mi casa es su casa,” His rugged, suntanned face exudes a quiet humility and keen curiosity shaped by his many years of desert life. Later, he puts his arm around me, and Dick snaps my photo.

The pale sky-blue adobe walls in the front room are lined with ollas and vases, glazed in a rainbow of rust-red, brown, and eggshell hues and painted with intricate, geometric designs. Sunlight, streaming through the thin violet-blue curtains, casts an iridescent glow on them. I am mesmerized by their spiral, thin-walled shapes and meticulously painted and etched patterns.

The pale sky-blue adobe walls in the front room are lined with ollas and vases, glazed in a rainbow of rust-red, brown, and eggshell hues and painted with intricate, geometric designs. Sunlight, streaming through the thin violet-blue curtains, casts an iridescent glow on them. I am mesmerized by their spiral, thin-walled shapes and meticulously painted and etched patterns. My mind wanders as the room slowly fills with the lyrical beauty of Garcia’s baritone voice and guitar strumming. I gaze out the window. The heat glimmers over the parched, dust-colored land. Nothing seems to be alive except patches of creosote and agave clinging to the desert emptiness. How could such incredible artistic beauty come to exist in such a remote, hardscrabble place?

My mind wanders as the room slowly fills with the lyrical beauty of Garcia’s baritone voice and guitar strumming. I gaze out the window. The heat glimmers over the parched, dust-colored land. Nothing seems to be alive except patches of creosote and agave clinging to the desert emptiness. How could such incredible artistic beauty come to exist in such a remote, hardscrabble place? “The first time I saw those pieces,” Juan tells me in Spanish, “I knew I had found a hidden treasure. I knew that the ancient ones must have found the materials here.” Over many years, he has patiently experimented with different clays, pigments, drawing and firing techniques to make ollas or pots with the ancient culture’s iconography and design.

“The first time I saw those pieces,” Juan tells me in Spanish, “I knew I had found a hidden treasure. I knew that the ancient ones must have found the materials here.” Over many years, he has patiently experimented with different clays, pigments, drawing and firing techniques to make ollas or pots with the ancient culture’s iconography and design.

Like a tale out of the Wizard of Oz, it began in 1976 when MacCallum stopped off at a second-hand swap shop in the New Mexico border town of Deming where he bought three unsigned pots. Intrigued by their intricate beauty and wondering if they were pre-Columbian in origin, he embarked on an adventure south that would take him to Mata Ortiz and the unknown potter.

Like a tale out of the Wizard of Oz, it began in 1976 when MacCallum stopped off at a second-hand swap shop in the New Mexico border town of Deming where he bought three unsigned pots. Intrigued by their intricate beauty and wondering if they were pre-Columbian in origin, he embarked on an adventure south that would take him to Mata Ortiz and the unknown potter. The homes, some humble brick adobes; others larger cinder-block buildings, resonate with an infectious warmth and vitality for work. Children breeze in and out as if flying on broomsticks. Pots and vases line oilcloth-covered tables. I look over the shoulders of men and women as they shape, polish and paint at tiny sunlit work stations. They shape the lower portion of the object in a plaster mold, place a single coil of clay atop it, and then by hand work the clay upwards to form their thin-walled bowls, jars, and pots.

The homes, some humble brick adobes; others larger cinder-block buildings, resonate with an infectious warmth and vitality for work. Children breeze in and out as if flying on broomsticks. Pots and vases line oilcloth-covered tables. I look over the shoulders of men and women as they shape, polish and paint at tiny sunlit work stations. They shape the lower portion of the object in a plaster mold, place a single coil of clay atop it, and then by hand work the clay upwards to form their thin-walled bowls, jars, and pots. Today, one of Quezada’s pots can sell for thousands of dollars. In 1999, he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, Mexico’s highest award given to a living Mexican-born artist.

Today, one of Quezada’s pots can sell for thousands of dollars. In 1999, he received the Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes, Mexico’s highest award given to a living Mexican-born artist.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts.

I wound my way through the ruins on a trail which took me backward in time. Pueblo Grande began as a small settlement around AD 450 and grew to over fifteen hundred people. The mound village was one of the largest Hohokam settlements in the area. At one time there were over fifty mound villages in the Salt River Valley. They got their names from the platform mounds at their centre. The mounds were urban centres with large open plazas where ceremonies were likely performed and were built with trash or soil and then capped with caliche, a lime-rich soil found in the desert which makes a good plaster when mixed with water. Pueblo Grande also included residential “suburbs”, astronomical observation facilities, waste disposal facilities, and ball courts. I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

I walked past the remains of the platform mound, the ball court, special purpose rooms, and the Solstice Room. At summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset, the sun’s rays passed through the corner door and onto another door in the middle of the south wall of the Solstice Room. Some researchers think the room may have been used as a calendar.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had.

Pueblo Grande was built at the headwaters of a major canal system. The Hohokam cultivated many plant species, including maize, cotton, squash, amaranth, little barley, and beans. Unlike today, The Salt River ran year round during Hohokam days. But the arid desert environment did not produce enough rainfall to grow crops. The Hohokam built over one thousand miles of canals and engineered the largest and most sophisticated irrigation system in the Americas, no small feat considering the primitive tools they had. Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Mesa Grande Cultural Park contains the ruins of a temple mound built by the Hohokam between AD 1100 and AD 1400. At first glance, I was not impressed with the site. Just a mound of dirt and a ditch. The site became more interesting as I walked through it and viewed it in context of the historical information provided on sign posts. The Park of the Canals contains no mound village but displays the remains of over four thousand feet of Hohokam canals in three different sections. Also located with the Park is the Brinton Desert Botanical Garden, a small garden containing plants found within the desert environment.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.

Canals remain important to irrigation within the greater Phoenix area today with nine major canals and over nine hundred miles of “laterals”, ditches taking water from the canals to delivery points. Paths alongside the waterways are used for walking, running and biking. Scottsdale, one of the other cities in the greater Phoenix area, has turned a canal area into a modern meeting place and tourist draw. The banks of Scottsdale Waterfront, in a revitalized area of downtown Scottsdale, are lined with palm trees, public art, courtyards, fountains, and walking paths. The area contains restaurants, outdoor cafés, specialty shops, and high-rise residential buildings, and hosts music and art festivals. It feels worlds away from its ancient Hohokam roots.