Jekyll Island, Georgia

by Theresa St. John

Catching sight of the stark remains of Horton House, a two-story tabby structure now tucked beneath the shady branches of Jekyll Island’s Live Oaks, I felt as if I’d taken a step backwards in the pages of a history book. This was once a thriving plantation that became a prime target during the Spanish raid in 1742,

During my recent stay on Jekyll Island, the hotel manager asked what I was interested in doing while vacationing there. I explained that I loved history and wanted to learn about anything historical on the island. He laughed out loud and told me I’d need more than three days to see it all, but he’d be glad to give me some suggestions. Horton House was on the top of his list.

He explained that Horton House was one of the oldest standing tabby structures in the state of Georgia. When I looked at him strangely, he laughed again.

He explained that Horton House was one of the oldest standing tabby structures in the state of Georgia. When I looked at him strangely, he laughed again.

“Most people don’t know what tabby is, don’t feel bad.” he said.” It was the typical building material of the 18th and 19th century. People would burn oyster shells and use the ash, otherwise known as lime, then fold in equal parts of sand, water and crushed shells. This gave them a significantly strong and thick mixture.” He continued to explain the process to me.

When I told him I was interested in hearing more, he continued: “They’d pour it into large forms that had been made with two parallel planks of wood These would measure the length of the structure’s outer walls. When each tabby mixture had set, the boards would be moved upwards repeatedly, until the desired height of the home was reached. If you really love history, you don’t want to miss this piece of it!”

When I told him I was interested in hearing more, he continued: “They’d pour it into large forms that had been made with two parallel planks of wood These would measure the length of the structure’s outer walls. When each tabby mixture had set, the boards would be moved upwards repeatedly, until the desired height of the home was reached. If you really love history, you don’t want to miss this piece of it!”

He pointed his finger to the right and said “It’s about five miles, that way.” I decided to jump on the old-fashioned bicycle I’d rented for the day and pedal along the winding bike paths, while getting a feel for this beautiful 22-mile island. I’d take in the sight of its picturesque oak trees, with their strong branches draped in heavy moss, bending over the roads and walkways, while keeping a keen eye out for the old manor.

The moment I caught sight of the ruins of Horton House, I stopped short. With its scarred openings for windows and wide-open doorways, this deserted house echoed with the drama of its last inhabitants. Its two-story structure stood proudly beneath the overhanging beauty of gigantic tree branches. I jumped off the bike and parked it nearby.

The moment I caught sight of the ruins of Horton House, I stopped short. With its scarred openings for windows and wide-open doorways, this deserted house echoed with the drama of its last inhabitants. Its two-story structure stood proudly beneath the overhanging beauty of gigantic tree branches. I jumped off the bike and parked it nearby.

I took my time and studied each of the reader boards placed around the property, wanting to learn as much as I could about Jekyll Island’s 18th and 19th century history. As I read more about the unique building material called ‘tabby’ and wandered around both inside and outside of this open-air building, I could clearly see the remaining shells in every wall.

The house was built by Major William Horton, second in command, serving under General James Oglethorpe and in charge of troops that were entrenched further North, on St. Simon’s Island. Horton House is surrounded by rich land, which was perfect for harvesting cotton and indigo, as well as hops and barley. Horton actually produced Georgia’s first beer and supplied ale to the troops and settlers at nearby Ft Frederica. I wondered what a cold glass of that had tasted like, way back when!

The house was built by Major William Horton, second in command, serving under General James Oglethorpe and in charge of troops that were entrenched further North, on St. Simon’s Island. Horton House is surrounded by rich land, which was perfect for harvesting cotton and indigo, as well as hops and barley. Horton actually produced Georgia’s first beer and supplied ale to the troops and settlers at nearby Ft Frederica. I wondered what a cold glass of that had tasted like, way back when!

The structure standing today is actually Horton’s second home. The first was a wooden building, destroyed by fire after the Spanish were defeated in 1742 and made a hasty retreat from the area, having lost the battle of Bloody Marsh.

Horton, the first Englishman to own property on the Island, obtained these 500-acres by means of a land grant in 1735, when he sailed to America on the Symond, a passenger ship.

One of the land grant conditions stated that Horton would have to bring 10 indentured servants with him from England, one for each fifty acres of land. He was also required to have 20% of the land cultivated and sustainable, within the first ten years of his settling in Georgia.

One of the land grant conditions stated that Horton would have to bring 10 indentured servants with him from England, one for each fifty acres of land. He was also required to have 20% of the land cultivated and sustainable, within the first ten years of his settling in Georgia.

When he initially came to the Island, it was extremely isolated. His closest neighbors were at Frederica, another settlement further North,on St.Simons Island. Fort Frederica is where Horton was promoted to Major, and became second in command under Oglethorpe. The fort served to protect settlers from Spanish and Native American attacks. In 1742, the British withstood an onslaught there, in the battle of Bloody Marsh, a siege now firmly ensconced in Georgia’s rich history.

William Horton is also responsible for cutting a road across the north end of Jekyll Island, running East and West, from his house to the beach. Today, it is still called Horton Road. Horton passed away in 1748 while in Savannah.

In 1791, four Frenchmen from Sapelo Island jointly purchased Jekyll Island. Later, one of them, Poulain du Bignon, became the sole owner. As a young officer, Poulain served in the French Army in India, fighting against Great Britain. Later, he commanded a French Naval vessel. He moved into Horton House in1792, several years after the American Revolution. Bignon died in 1825. He was eighty-six. He’s buried with other members of his family, across the street from Horton House, with a peaceful view of Bignon Creek. A single oak tree marks his passing.

In 1791, four Frenchmen from Sapelo Island jointly purchased Jekyll Island. Later, one of them, Poulain du Bignon, became the sole owner. As a young officer, Poulain served in the French Army in India, fighting against Great Britain. Later, he commanded a French Naval vessel. He moved into Horton House in1792, several years after the American Revolution. Bignon died in 1825. He was eighty-six. He’s buried with other members of his family, across the street from Horton House, with a peaceful view of Bignon Creek. A single oak tree marks his passing.

I have always loved historic graveyards and was excited to see that this one was a little different than others I’m used to, due to it’s simplicity and size. A tabby enclosure surrounds the small family plot and you can sit on a wooden bench nearby, overlooking the creek. It was windy the morning I went and it was as if I could hear voices from the distant past, carried on the breeze that whispered through the swaying tree branches.

The remaining Bignon family continued to own Jekyll Island, working together to manage the plantation and it’s crops. Eventually they decided to sell the property to a group of millionaires in 1886. They, in turn, promptly formed The Jekyll Island Club, a playground for the rich and famous. Many of the world’s wealthiest families became members in it’s heyday. Most notably were the Morgan, Vanderbilt and Rockefeller empires.Today, the Jekyll Island Club is a luxury resort and a member of the Historic Hotels Of America.

The remaining Bignon family continued to own Jekyll Island, working together to manage the plantation and it’s crops. Eventually they decided to sell the property to a group of millionaires in 1886. They, in turn, promptly formed The Jekyll Island Club, a playground for the rich and famous. Many of the world’s wealthiest families became members in it’s heyday. Most notably were the Morgan, Vanderbilt and Rockefeller empires.Today, the Jekyll Island Club is a luxury resort and a member of the Historic Hotels Of America.

Jekyll Island lies off the coast of Georgia and is known as one of the Golden Isles. It’s one of four barrier Islands, which also includes St. Simons Island, Sea Island, Little St. Simons Island and nearby Brunswick. It’s exquisite beauty and warm invitation to the endless adventure there is unrivaled. With museums, hotels, gorgeous beaches and historic places preserved with great diligence and care, you won’t mind paying the $6 to gain entrance and you won’t want to miss this amazing piece of history.

If You Go:

Jekyll Island Chamber of Commerce

About the author:

Theresa St.John is a freelance travel writer and photographer based in Saratoga Springs, New York. Even though history was not on her radar while in high school, she has a deep interest in all things historical now. She has been on assignment for several magazines and is published in both print and on-line venues. Last year she traveled to Ireland on assignment, which, she states ” was a trip of a lifetime.” She landed the cover photo and feature article in Vacation Rental Travels Magazine highlighting her adventures there. She has written for Great Escape, International Living, Saratoga Springs Life Magazine, The Observation Post newspaper, Discover Saratoga and is a successful contributor to many stock photography sites. She is the proud mom to two young men and Nonnie to 5 rescued dogs, 2 Chinchillas and a bird. Life is good, she says. Theresa vacations in Fiji this Fall and looks forward to another great travel writing/ photography opportunity in the South Pacific.

All photos by Theresa St. John:

Front view of Horton House

Bike path way with Georgia’s Live Oaks and hanging moss

Rustic bicycle outside Horton House

Tabby, typically used in the 18th and 19th century

Cemetery

Carved headstone

Cemetery with lone Live Oak tree

View of Horton House from distance

Pfeiffer had a penchant for fighting in the nude, or so it would seem. His first nude encounter happened on June 20, 1863, as a forty-one year-old captain based at Fort McRae, near today’s Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. (The fort has since been flooded by Elephant Butte Reservoir). The captain had taken ill and thought the hot springs, about six miles from the fort near the Rio Grande River, would be beneficial for his malady. He bathed in the curative springs, while his pregnant wife of seven years, Antonita, his adopted daughter Maria, and her attendant Mrs. Mercardo, bathed in a pool nearby. His three-year old son Albert had been left at the fort with servants. Additionally, soldiers accompanied the group to safeguard their bathing at El Ojo del Muerto, the Spring of the Dead.

Pfeiffer had a penchant for fighting in the nude, or so it would seem. His first nude encounter happened on June 20, 1863, as a forty-one year-old captain based at Fort McRae, near today’s Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. (The fort has since been flooded by Elephant Butte Reservoir). The captain had taken ill and thought the hot springs, about six miles from the fort near the Rio Grande River, would be beneficial for his malady. He bathed in the curative springs, while his pregnant wife of seven years, Antonita, his adopted daughter Maria, and her attendant Mrs. Mercardo, bathed in a pool nearby. His three-year old son Albert had been left at the fort with servants. Additionally, soldiers accompanied the group to safeguard their bathing at El Ojo del Muerto, the Spring of the Dead. Pfeiffer’s only thoughts were to save his wife and daughter. With his rifle lying close by, he instinctively leapt for the rifle, running to the safety of the nearby river bank, completely nude. Clothes were the least of his concern. According to the November 1933 issue of The Colorado Magazine, “He was followed by the Indians who shot at him, one of the arrows entering his back with the end coming out in front. In this condition, with the arrow in his back, he ran until he reached an enclosure of rock where he made a halt to rest and defend himself.” Later, he arrived at the fort with an embedded arrow just below his heart, more dead than alive. Still naked, Pfeiffer was barely recognizable as his sunburned skin peeled off in layers. “When the surgeon drew out the arrow from his back, the sun-scorched skin surrounding the wound came off with it, and for days the Captain suffered intense agony and lay for two months at the point of death,” according to the magazine.

Pfeiffer’s only thoughts were to save his wife and daughter. With his rifle lying close by, he instinctively leapt for the rifle, running to the safety of the nearby river bank, completely nude. Clothes were the least of his concern. According to the November 1933 issue of The Colorado Magazine, “He was followed by the Indians who shot at him, one of the arrows entering his back with the end coming out in front. In this condition, with the arrow in his back, he ran until he reached an enclosure of rock where he made a halt to rest and defend himself.” Later, he arrived at the fort with an embedded arrow just below his heart, more dead than alive. Still naked, Pfeiffer was barely recognizable as his sunburned skin peeled off in layers. “When the surgeon drew out the arrow from his back, the sun-scorched skin surrounding the wound came off with it, and for days the Captain suffered intense agony and lay for two months at the point of death,” according to the magazine.

Pfeiffer was so despondent over the loss of his family that he vowed to kill Apaches to avenge their death. It almost became a passion. The Colorado Chieftain newspaper on June 29, 1871, read: “It was a bad day for the Apaches when they killed old Pfeiffer’s family. He made several trips, alone, into their country, staying, sometimes for months, and always seemed pleased, for a few days, on his return. He was always accompanied by about half a dozen wolves in the Apache country. ‘They like me,’ he said once, ‘because they’re fond of dead Indian, and I feed them well.'”

Pfeiffer was so despondent over the loss of his family that he vowed to kill Apaches to avenge their death. It almost became a passion. The Colorado Chieftain newspaper on June 29, 1871, read: “It was a bad day for the Apaches when they killed old Pfeiffer’s family. He made several trips, alone, into their country, staying, sometimes for months, and always seemed pleased, for a few days, on his return. He was always accompanied by about half a dozen wolves in the Apache country. ‘They like me,’ he said once, ‘because they’re fond of dead Indian, and I feed them well.'” The Utes and the Navajos both revered the healing powers of the hot springs, located at modern-day Pagosa Springs, in southwestern, Colorado. The Utes had laid claim to the land generations prior to the Navajo challenge, but shared the springs because of their sacred origins. Then, in late 1866, the Navajo challenged the Utes for control of the springs, fighting for several days to stake their claim. Unfortunately, it ended in a stalemate.

The Utes and the Navajos both revered the healing powers of the hot springs, located at modern-day Pagosa Springs, in southwestern, Colorado. The Utes had laid claim to the land generations prior to the Navajo challenge, but shared the springs because of their sacred origins. Then, in late 1866, the Navajo challenged the Utes for control of the springs, fighting for several days to stake their claim. Unfortunately, it ended in a stalemate.

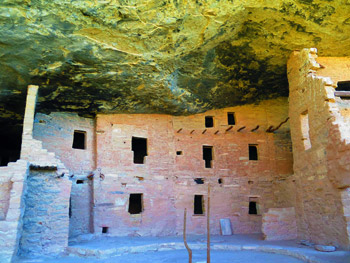

Evidence of settlement on the Colorado Plateau only dates back to AD 550, but signs of human presence on the plateau go back at least 10,000 years to the Paleolithic Age. For much of the known history of these people, they existed as tribes of wandering hunter gathers. Forging for food is easier than farming.

Evidence of settlement on the Colorado Plateau only dates back to AD 550, but signs of human presence on the plateau go back at least 10,000 years to the Paleolithic Age. For much of the known history of these people, they existed as tribes of wandering hunter gathers. Forging for food is easier than farming. The Anasazi are rich in history. What is emerging is from the archeology work is a complex and, somewhat egalitarian, society. They succeeded to thrive for millennium in a sparse land with harsh winters. The archeological evidence of the Anasazi date back to 1200 BC—a time known as the “Basket Making Era” since they had baskets, but no pottery, and lived in camps or caves, surviving off a staple of cultivated squash and corn.

The Anasazi are rich in history. What is emerging is from the archeology work is a complex and, somewhat egalitarian, society. They succeeded to thrive for millennium in a sparse land with harsh winters. The archeological evidence of the Anasazi date back to 1200 BC—a time known as the “Basket Making Era” since they had baskets, but no pottery, and lived in camps or caves, surviving off a staple of cultivated squash and corn.

If you’re coming from Denver, you’ll enjoy the scenic, mountain-carved route along US Highway 160W and US 285S. I drove in from Grand Junction, along US 50. If you can do this drive in the fall, roll your windows down and you can smell the yellow and red leaves bursting in bright patches amongst ever-steady green pines. Carved cliffs of rock will add earthy tones to the pallet, and blue sky might cause you to turn the radio down so as to let the evolving panoramic fill your senses.

If you’re coming from Denver, you’ll enjoy the scenic, mountain-carved route along US Highway 160W and US 285S. I drove in from Grand Junction, along US 50. If you can do this drive in the fall, roll your windows down and you can smell the yellow and red leaves bursting in bright patches amongst ever-steady green pines. Carved cliffs of rock will add earthy tones to the pallet, and blue sky might cause you to turn the radio down so as to let the evolving panoramic fill your senses.

In San Ángel, the two artists fed, and bled, off each other. Medical problems plagued Frida, and her third pregnancy ended in yet another abortion. Diego had affairs, including one with Frida’s own sister, Cristina, resulting in a temporary separation. But Frida’s artistic and intellectual power also grew during this time, not only thanks to her husband, but also to the circle they drew around them. There, the surrealist André Breton recognized Frida’s talent and offered to show her work in Paris. Not long after, she gave her first solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City. The San Ángel house was an incubator for both Frida’s talent and her misery. The two went hand in hand, as she painted portrait after portrait of herself in the form of an invalid and scorned woman, sad and withering away just as her star began to grow. Yet, through all this, Frida was slowly, but surely, becoming recognized for something more than her marriage to Diego Rivera. She was an artist in her own right, standing on her own two, albeit crippled, feet.

In San Ángel, the two artists fed, and bled, off each other. Medical problems plagued Frida, and her third pregnancy ended in yet another abortion. Diego had affairs, including one with Frida’s own sister, Cristina, resulting in a temporary separation. But Frida’s artistic and intellectual power also grew during this time, not only thanks to her husband, but also to the circle they drew around them. There, the surrealist André Breton recognized Frida’s talent and offered to show her work in Paris. Not long after, she gave her first solo exhibition at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City. The San Ángel house was an incubator for both Frida’s talent and her misery. The two went hand in hand, as she painted portrait after portrait of herself in the form of an invalid and scorned woman, sad and withering away just as her star began to grow. Yet, through all this, Frida was slowly, but surely, becoming recognized for something more than her marriage to Diego Rivera. She was an artist in her own right, standing on her own two, albeit crippled, feet.

While Plaza San Jacinto is the neighborhood’s most popular outdoor space, the neighboring church (of the same name) provides a much more beautiful and calm place in which to rest. The Iglesia de San Jacinto was built in the 16th century, and feels almost lost in time. Both the building and its garden predate the Great Fire of London, with an architecture and sensibility that might be more at home in Italy, or France, than Mexico. The cloister feels Tuscan, the sanctuary Spanish. The garden is wonderfully wild, almost English in style, hidden behind large stone walls, yet easily accessible through both the church and a stone archway. It’s one of the most serene places in Mexico City, a beautiful spot to rest and contemplate, and begin to understand how truly ancient this country is, even in its colonial manifestations.

While Plaza San Jacinto is the neighborhood’s most popular outdoor space, the neighboring church (of the same name) provides a much more beautiful and calm place in which to rest. The Iglesia de San Jacinto was built in the 16th century, and feels almost lost in time. Both the building and its garden predate the Great Fire of London, with an architecture and sensibility that might be more at home in Italy, or France, than Mexico. The cloister feels Tuscan, the sanctuary Spanish. The garden is wonderfully wild, almost English in style, hidden behind large stone walls, yet easily accessible through both the church and a stone archway. It’s one of the most serene places in Mexico City, a beautiful spot to rest and contemplate, and begin to understand how truly ancient this country is, even in its colonial manifestations. Frida’s painting, The Two Fridas, tackles that very same subject, and dates from the years in which she lived in San Ángel. In the double self-portrait, a European Frida holds the hand of an indigenous Mexican version of herself. Even more importantly, their bloodstreams are connected by an artery flowing from heart to heart, bleeding out one end. In many ways, The Two Fridas is about acceptance – of Kahlo’s ancestry, and of Mexico’s—though it’s also about struggle, both in her understanding of her own personal identity, and of her marriage. It’s no accident that Frida needs to hold her own hand in the picture. The Two Fridas was painted just as her marriage was falling apart, and she divorced Diego for the first time.

Frida’s painting, The Two Fridas, tackles that very same subject, and dates from the years in which she lived in San Ángel. In the double self-portrait, a European Frida holds the hand of an indigenous Mexican version of herself. Even more importantly, their bloodstreams are connected by an artery flowing from heart to heart, bleeding out one end. In many ways, The Two Fridas is about acceptance – of Kahlo’s ancestry, and of Mexico’s—though it’s also about struggle, both in her understanding of her own personal identity, and of her marriage. It’s no accident that Frida needs to hold her own hand in the picture. The Two Fridas was painted just as her marriage was falling apart, and she divorced Diego for the first time. Despite the tragedy that surrounded their relationship, Frida’s San Ángel house is not an inherently sad place to visit. It’s architecturally interesting, and provides a hands-on, visceral glimpse into the two artists’ lives—a chance to see the furniture, books and giant papier maché dolls that filled Diego’s studio, and the ghosts that are left behind in Frida’s. Outside, tall cactuses grow like relics of a great pre-Columbian past, and purple Jacaranda trees frame Frida’s part of the building, which like her house in Coyoacán is painted a deep, vibrant blue. For all the pain and hardship she endured there, her resilience shines through.

Despite the tragedy that surrounded their relationship, Frida’s San Ángel house is not an inherently sad place to visit. It’s architecturally interesting, and provides a hands-on, visceral glimpse into the two artists’ lives—a chance to see the furniture, books and giant papier maché dolls that filled Diego’s studio, and the ghosts that are left behind in Frida’s. Outside, tall cactuses grow like relics of a great pre-Columbian past, and purple Jacaranda trees frame Frida’s part of the building, which like her house in Coyoacán is painted a deep, vibrant blue. For all the pain and hardship she endured there, her resilience shines through.

Our journey to the isle, first recorded as Savary’s Island by Capt. George Vancouver in 1792, began at the ferry dock in Comox, Vancouver Island. An hour twenty later we were rolling off the Queen of Burnaby into Powell River back dropped by the serrated teeth of the majestic coastal mountain range. A half hour north landed us in Lund, a village dating from the 1880s when the two Thulin brothers from Sweden set up shop and named the community after one back home. Free parking is at a premium here but paid parking is available for daily fee of $7.00 at Dave’s parking lot. Savary emerged, a rich green line across the horizon, as we strolled the village boardwalk. Then we were off to our evening abode; a bed and breakfast south of Powell River.

Our journey to the isle, first recorded as Savary’s Island by Capt. George Vancouver in 1792, began at the ferry dock in Comox, Vancouver Island. An hour twenty later we were rolling off the Queen of Burnaby into Powell River back dropped by the serrated teeth of the majestic coastal mountain range. A half hour north landed us in Lund, a village dating from the 1880s when the two Thulin brothers from Sweden set up shop and named the community after one back home. Free parking is at a premium here but paid parking is available for daily fee of $7.00 at Dave’s parking lot. Savary emerged, a rich green line across the horizon, as we strolled the village boardwalk. Then we were off to our evening abode; a bed and breakfast south of Powell River. Stretched along the south shore, where we came ashore, were a line of substantial homes bordering the dirt road which we learned ran the length of the island, about 7.5 kilometres (.8 to 1.5 kilometres wide). Vehicles crowded a haphazard parking lot though few were to be found trundling along the low maintenance dirt roadways with the waning of summer. Admiring homes we walked as far south as the road allowed, drinking in views of beach and mountain. Perhaps appearing a tad bemused as we poured over a brochure we were rescued by a local resident who filled us in on the what’s and wherefore’s of Savary. She and her husband were just closing up their home for the season as were many of the locals; however there are a solid few who call Savary home full time and garner the fruits of civilized solitude in this stunning setting.

Stretched along the south shore, where we came ashore, were a line of substantial homes bordering the dirt road which we learned ran the length of the island, about 7.5 kilometres (.8 to 1.5 kilometres wide). Vehicles crowded a haphazard parking lot though few were to be found trundling along the low maintenance dirt roadways with the waning of summer. Admiring homes we walked as far south as the road allowed, drinking in views of beach and mountain. Perhaps appearing a tad bemused as we poured over a brochure we were rescued by a local resident who filled us in on the what’s and wherefore’s of Savary. She and her husband were just closing up their home for the season as were many of the locals; however there are a solid few who call Savary home full time and garner the fruits of civilized solitude in this stunning setting.

She told us of the Savary Island B & B; a single floor sprawling log building we had just passed and admired. There had been a couple hotels on the island – The Savary, built in 1914 survived until it burned down in 1932 and the Royal Savary Hotel at Indian Point which was demolished in 1982. Now B & Bs, cabin rentals and a lodge offer accommodation options. The listed permanent population of 100 balloons to a couple thousand in the summer.

She told us of the Savary Island B & B; a single floor sprawling log building we had just passed and admired. There had been a couple hotels on the island – The Savary, built in 1914 survived until it burned down in 1932 and the Royal Savary Hotel at Indian Point which was demolished in 1982. Now B & Bs, cabin rentals and a lodge offer accommodation options. The listed permanent population of 100 balloons to a couple thousand in the summer. A black dot on the water proved a large curious seal. Masked Killdeer complained as they wheeled about behind us and, usually solitary, Loons swam about in a group. We wore no watches. Time took on its own rhythm. Afterwards we sat on a log gazing towards the sea and enjoyed a snack. Never ceases to amaze me how food tastes better in such settings.

A black dot on the water proved a large curious seal. Masked Killdeer complained as they wheeled about behind us and, usually solitary, Loons swam about in a group. We wore no watches. Time took on its own rhythm. Afterwards we sat on a log gazing towards the sea and enjoyed a snack. Never ceases to amaze me how food tastes better in such settings. Striking out for the north beach and Mermaid Rock we returned to the dirt road, gloriously titled Vancouver Boulevard, running the spine of the island, and climbed to the height of land which was to take us through a protected and treed sand dunes section, devoid of development due to its fragility. Few cars and people frequented the roadway which felt much like a shady park walk.The takity takity tack of a noisy Piliated woodpecker echoed through the still forest; proving so intent on attacking his tree he took no notice of us. The protected zone is home to 10,000 year old sand dunes. The island is eroding steadily at both the north and south ends.

Striking out for the north beach and Mermaid Rock we returned to the dirt road, gloriously titled Vancouver Boulevard, running the spine of the island, and climbed to the height of land which was to take us through a protected and treed sand dunes section, devoid of development due to its fragility. Few cars and people frequented the roadway which felt much like a shady park walk.The takity takity tack of a noisy Piliated woodpecker echoed through the still forest; proving so intent on attacking his tree he took no notice of us. The protected zone is home to 10,000 year old sand dunes. The island is eroding steadily at both the north and south ends.