by Lynn Smith

For those people who have a passion for literature, history and London, a London guided walking tour will combine all these interests. There are several such tours available, led by knowledgeable guides, most of whom have been trained by the London Tourist Board. The tours are also reasonably priced.

Several months ago, on a visit to London, I opted to take such a tour and chose the Bloomsbury walking tour as I have always been fascinated by Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury group.

Several months ago, on a visit to London, I opted to take such a tour and chose the Bloomsbury walking tour as I have always been fascinated by Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury group.

I met the tour guide outside Russell Square Underground and we began the two hour walk from there. It was a beautiful summer’s day which allowed us to see the green and pleasant squares at their best.

Bloomsbury is in the Borough of Camden and is bounded on the north by Euston Rd, Gray’s Inn Rd on the east, Tottenham Court Rd on the west and High Holborn on the south side.

The area has a fascinating history. The name Bloomsbury is a corruption of “Blemonde” which was the name of Baron Blemonde, William the Conqueror’s vassal who received the land from William in the 11th century.

In the 18th century, Bloomsbury was open country and was considered to be very healthy. In 1660 the Earl of Southampton built his house there and laid down an attractive square in front of the house. The borough took shape as more aristocrats discovered the area; the Duke of Montague built a stylish house on the site of what is now the British Museum and the great landowning family of the Russells, the Dukes of Bedford, Gordon and Brunswick all built their mansions in the area.

In the 18th century, Bloomsbury was open country and was considered to be very healthy. In 1660 the Earl of Southampton built his house there and laid down an attractive square in front of the house. The borough took shape as more aristocrats discovered the area; the Duke of Montague built a stylish house on the site of what is now the British Museum and the great landowning family of the Russells, the Dukes of Bedford, Gordon and Brunswick all built their mansions in the area.

In the 19th century, Bloomsbury lost some of its glamour – trade and industry moved in and the area was no longer considered to be fashionable. The British Museum was erected on its present site in 1823 and London University began in 1827.

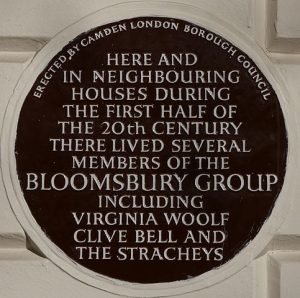

The arrival of the Bloomsbury Group in the early 20th century gave the area its reputation as an intellectual, artistic and somewhat Bohemian area – a reputation which is still considered relevant today.

Virginia Woolf (born Stephen, 1882 – 1941) was the third child of Sir Leslie Stephen and his wife Julia. Virginia’s siblings were Vanessa, Thoby and Adrian. The family lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate, a large house always filled with children, friends and family.

The Stephen children grew up in a literary household – Sir Leslie was a journalist and had a well-stocked library, to which Virginia had unrestricted access.

When she was thirteen, Virginia’s beloved mother died and this traumatic event caused her first mental breakdown; this was followed by another breakdown when her father died in 1904. After Sir Leslie’s death the Stephen children decided to leave Hyde Park Gate (with its unhappy memories) and move to Gordon Square, in the heart of Bloomsbury, just north of the University of London.

Gordon Square is on the corner of Gordon Rd and Tavistock Place. No. 46, the house the Stephen children moved into, in 1904, was a large, elegant building, fronted by the pretty garden square. The Stephens’uncles and aunts, however, frowned on the move as Gordon Square was not considered a desirable address.

Gordon Square is on the corner of Gordon Rd and Tavistock Place. No. 46, the house the Stephen children moved into, in 1904, was a large, elegant building, fronted by the pretty garden square. The Stephens’uncles and aunts, however, frowned on the move as Gordon Square was not considered a desirable address.

Gordon Square soon became a meeting place for Thoby Stephen’s Cambridge friends. Other visitors were Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and later, Leonard Woolf. Virginia and Vanessa both took part in the lively discussions at these meetings, which could be described as the beginnings of the Bloomsbury Group.

After Thoby’s death from typhoid in 1906 and Vanessa’s marriage to Clive Bell shortly after, Virginia and Adrian left Gordon Square and rented a house at 29 Fitzroy Square.

Fitzroy Square

Although still in the Borough of Camden, Fitzroy Square is not strictly Bloomsbury but Fitzrovia, just further south of Tottenham Court Rd. The area was originally developed to provide houses for the aristocracy and many elegant mansions were erected, designed by Robert Adam. Building began in 1792 and was eventually finished in 1835.

In 1907, when the Stephens moved into 29 Fitzroy Square, the area consisted mainly of offices, workshops and lodging-houses. These unpretentious surroundings suited the brother and sister; they carried on with the Gordon Square intellectual get-togethers and the circle soon grew. An important addition to their gatherings was Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) – that eccentric and Bohemian patron of the arts, who lived in nearby Bedford Square.

The years at Fitzroy Square were eventful ones for Virginia – her two nephews (Vanessa’s sons) were born in 1908 and 1910 and in 1909 she accepted Lytton Strachey’s proposal of marriage but, by mutual consent, the engagement was cancelled almost immediately.

When the lease of 29 Fitzroy Square came to an end in 1911, Virginia and Adrian leased a four-storey house, No 38 Brunswick Square, which they shared with Maynard Keynes and Duncan Grant. While living in Brunswick Square, Virginia became engaged to Leonard Woolf and they were married on 10 Aug. 1912. The Woolfs went to live in Sussex where Virginia had taken a five-year lease on Asheham House. It was to be another twelve years before Virginia moved back to Bloomsbury.

The intervening years 1912 -1924

During the years that Virginia was living elsewhere, she published four books and had, unfortunately, another serious mental breakdown from which she was slow to recover. The Woolfs moved to Hogarth House in Richmond and in 1917 they bought a hand-press – and so began Hogarth Press; soon they were printing pamphlets, books and slim volumes of poetry, mainly the works of the Bloomsbury Group.

In January 1924 Virginia bought the lease of 52 Tavistock Square and the Woolfs, together with the Hogarth Press, moved into their new premises in March, where the Press was established in the basement. Tavistock Square was part of the Russell family, the Dukes of Bedford’s estate and No 52 was a typical terraced house.

In January 1924 Virginia bought the lease of 52 Tavistock Square and the Woolfs, together with the Hogarth Press, moved into their new premises in March, where the Press was established in the basement. Tavistock Square was part of the Russell family, the Dukes of Bedford’s estate and No 52 was a typical terraced house.

The years spent at Tavistock Square were Virginia’s most productive and she became much sought after as a guest speaker at various prestigious universities.

Today, Tavistock Square is surrounded by a number of famous buildings, all of which are worth investigating. The Square was also the scene of the suicide bombings in 2005, in which 13 people were killed.

Mecklenburgh Square was Virginia Woolf’s final Bloomsbury residence. Like Brunswick Square, Mecklenburgh Square was part of the grounds of the Foundling Hospital and was named after King George III’s wife, Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg.

The 2 acres of gardens are beautifully laid out, with lawns, trees and pathways. The gardens are only open to the public on two days a year. The rest of the year, the gardens are only open to resident key-holders.

No. 37 which the Woolfs leased, was once again, a large terrace house facing the square. They operated the Hogarth Press from No 37. The house was badly damaged during the bombing of London in 1940.

In 1941, Virginia, fearing another onslaught of her mental condition, committed suicide by drowning herself in the River Ouse.

A walk through Bloomsbury is certainly an experience not to be forgotten. There is so much of interest – graceful, elegant architecture, quiet, peaceful gardens and the all-pervading atmosphere of intelligentsia.

It is no wonder that the Bloomsbury Group put down roots here and kept returning to the area throughout their lives.

After my walking tour was over, I certainly felt that I’d come to know Virginia Woolf and her group on a much more personal level.

References: 1975. Lehmann, John. Virginia Woolf and her World. London: Thames and Hudson.

If You Go:

♦ Contact www.walklondon-uk.com or www.walks.com for information about the tours, what is on offer, where to meet, etc.

♦ Wear comfortable shoes, take an umbrella and something to drink if it is hot.

♦ Don’t forget your camera and be prepared to walk for a good couple of hours, although the pace is not fast.

♦ The guides are knowledgeable and enjoy answering questions. Now is your opportunity to get answers to those questions you’ve always wanted to ask.

♦ Make the most of the tour and enjoy it.

Photo credits:

Gordon Square, London by Paul the Archivist / CC BY-SA

Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford / Public domain

Bloomsbury group blue plaque by Edwardx / CC BY-SA

Gordon Square park by Stephen McKay / Gordon Square, Bloomsbury

Tavistock Square by Ewan Munro from London, UK / CC BY-SA

Browse London Historic Walking Tours Now Available

About the author:

Lynn is a retired librarian who lives in Durban, South Africa. She lived in London for some time many years ago and has returned to visit several times in the past few years. Her last visits overseas were to Eastern Europe where she fell in love with Prague and Budapest. When not travelling, Lynn enjoys writing articles for the internet and does freelance editing and proof-reading. She is a keen gardener and shares her home with her six beloved cats.

Brighton’s train station is still magnificently Victorian, with its soaring iron roof. The formerly sleepy fishing village of Brighthelmstone began to be transformed towards the end of the eighteenth century when the aristocracy arrived ‘to take the waters’, but it wasn’t until the arrival of the railway in the 1840s, that Brighton really put itself on the map and became the destination of choice for toffs and day-trippers alike.

Brighton’s train station is still magnificently Victorian, with its soaring iron roof. The formerly sleepy fishing village of Brighthelmstone began to be transformed towards the end of the eighteenth century when the aristocracy arrived ‘to take the waters’, but it wasn’t until the arrival of the railway in the 1840s, that Brighton really put itself on the map and became the destination of choice for toffs and day-trippers alike. I took a walk along the sea-front, breathing deeply of the sea air, and made a nostalgic detour to the pier, complete with funfair and fish and chips. I visited the small but perfectly-formed Fishing Museum. The fishermen of Brighthelmstone were not best pleased at the arrival of all these new visitors, but they made the best of it.

I took a walk along the sea-front, breathing deeply of the sea air, and made a nostalgic detour to the pier, complete with funfair and fish and chips. I visited the small but perfectly-formed Fishing Museum. The fishermen of Brighthelmstone were not best pleased at the arrival of all these new visitors, but they made the best of it. When it came to mistresses and houses, the Prince Regent was a lover of excess. ‘The more, the merrier’ would appear to be his motto. His mistresses were plump and matronly, and his houses extravagant.

When it came to mistresses and houses, the Prince Regent was a lover of excess. ‘The more, the merrier’ would appear to be his motto. His mistresses were plump and matronly, and his houses extravagant.

On top of the cliff, the concrete observation tower built during the German occupation of the Channel Islands stands at attention and fixes its martial gaze into the distance. Below, at the bottom of the cliff, covered by the high tide, is the graveyard of the guns. These are heavy artillery weapons captured by the Germans during World War II and thrown over the cliff by British forces after the liberation of the islands. This is within living memory. There are still people who remember those terrible times.

On top of the cliff, the concrete observation tower built during the German occupation of the Channel Islands stands at attention and fixes its martial gaze into the distance. Below, at the bottom of the cliff, covered by the high tide, is the graveyard of the guns. These are heavy artillery weapons captured by the Germans during World War II and thrown over the cliff by British forces after the liberation of the islands. This is within living memory. There are still people who remember those terrible times.

Manpower was needed in order to build trenches, anti-tank walls, bunkers, gun emplacements, observation towers and tunnels. The Organisation Todt was in charge of providing workers. Its primary source were prisoners of war in mainland Europe, political prisoners and even men rounded up on the Continent. These poor men were treated worse than slaves. The Russians bore the brunt of Nazi cruelty as they were considered sub-humans. Many tried to escape the labour camps in search of food and some locals, running enormous risks, gave them food and shelter.

Manpower was needed in order to build trenches, anti-tank walls, bunkers, gun emplacements, observation towers and tunnels. The Organisation Todt was in charge of providing workers. Its primary source were prisoners of war in mainland Europe, political prisoners and even men rounded up on the Continent. These poor men were treated worse than slaves. The Russians bore the brunt of Nazi cruelty as they were considered sub-humans. Many tried to escape the labour camps in search of food and some locals, running enormous risks, gave them food and shelter. Visitors can see the original operating theatre, the boiler room and telephone exchange. There also other exhibits, like the clandestine crystal radios people used to listen to news from the outside world at the risk of imprisonment or even death. There’s even an Enigma machine on display, which reminded me of World War II movies and made me smile.

Visitors can see the original operating theatre, the boiler room and telephone exchange. There also other exhibits, like the clandestine crystal radios people used to listen to news from the outside world at the risk of imprisonment or even death. There’s even an Enigma machine on display, which reminded me of World War II movies and made me smile. It occurred to me that my own grandfather could have been among those labourers in Jersey had he not been rescued by the Argentinean government just in the nick of time. He was in the concentration camp at Argelès-Sur-Mer, close to the Spanish border. He is an Argentinean national but he was living in Spain when the war broke out and since his parents were Spanish, he was considered a Spaniard and recruited by the Republican side without further ado.

It occurred to me that my own grandfather could have been among those labourers in Jersey had he not been rescued by the Argentinean government just in the nick of time. He was in the concentration camp at Argelès-Sur-Mer, close to the Spanish border. He is an Argentinean national but he was living in Spain when the war broke out and since his parents were Spanish, he was considered a Spaniard and recruited by the Republican side without further ado.

Hinterland was the first network television series (a combined Fiction Factory production for Welsh language channel S4C and the BBC) filmed in Ceredigion; probably because its lack of motorways makes it difficult to reach for film crews. Its stark location was part of the appeal though, according to series producer Ed Talfan on the BBC Hinterland blog page:

Hinterland was the first network television series (a combined Fiction Factory production for Welsh language channel S4C and the BBC) filmed in Ceredigion; probably because its lack of motorways makes it difficult to reach for film crews. Its stark location was part of the appeal though, according to series producer Ed Talfan on the BBC Hinterland blog page: I wrote an article about the Cambrian line railway journey still available on what was Suite 101 years ago, and this year wrote a poem about a possible railway journey from Scarborough on Britain’s east coast to Aberystwyth on the west.

I wrote an article about the Cambrian line railway journey still available on what was Suite 101 years ago, and this year wrote a poem about a possible railway journey from Scarborough on Britain’s east coast to Aberystwyth on the west. Circling the headland again, I saw the waves looked even higher as they crashed onto the south beach and defensive walls between the sea and harbour. So I walked down as far as I could, and was rewarded with excellent views and photos of the sun setting over the highest southern peak; between swirling grey clouds and above seawater flying high into the air after battering the promenade.

Circling the headland again, I saw the waves looked even higher as they crashed onto the south beach and defensive walls between the sea and harbour. So I walked down as far as I could, and was rewarded with excellent views and photos of the sun setting over the highest southern peak; between swirling grey clouds and above seawater flying high into the air after battering the promenade. A Welsh uprising against the rule of Henry IV under Owain Glyndwr captured the castle in 1404. He crowned himself Prince of Wales, and held a parliament at Machynlleth. Mach is a few stops on the trainline east of Aber, where the train can divide into two: one continuing east-west, and the other riding the south-north coast line to Pwllheli. The rebellion lost the castle in 1408, and order was restored under Henry V by 1415.

A Welsh uprising against the rule of Henry IV under Owain Glyndwr captured the castle in 1404. He crowned himself Prince of Wales, and held a parliament at Machynlleth. Mach is a few stops on the trainline east of Aber, where the train can divide into two: one continuing east-west, and the other riding the south-north coast line to Pwllheli. The rebellion lost the castle in 1408, and order was restored under Henry V by 1415. Aber town centre is quite small and easy to navigate. Walking out from the station the north beach is straight ahead past a pub sarcastically named after Lord Beechings. Lord Beeching’s report closed down the fifty-miles long Aberystwyth to Carmarthen train line linking mid and south Wales in 1965.

Aber town centre is quite small and easy to navigate. Walking out from the station the north beach is straight ahead past a pub sarcastically named after Lord Beechings. Lord Beeching’s report closed down the fifty-miles long Aberystwyth to Carmarthen train line linking mid and south Wales in 1965. Under the bridges, the Mynach falls 300 feet in five steps to the Rheidol. The Devil’s Bridge name was inspired by a local legend that thought the original bridge was too difficult to build, so the Devil must have built it in exchange for the first soul that crossed. An old woman tricked the Devil by sending her dog onto the bridge. It’s a nice story, but a shame for her dog!

Under the bridges, the Mynach falls 300 feet in five steps to the Rheidol. The Devil’s Bridge name was inspired by a local legend that thought the original bridge was too difficult to build, so the Devil must have built it in exchange for the first soul that crossed. An old woman tricked the Devil by sending her dog onto the bridge. It’s a nice story, but a shame for her dog!

From London to York

From London to York Rising the next morning to very un-English like weather ( read “sunny” ) the three of us headed for Petersfield, south of London. During our stay this would be our home away from home. Founded in the 12th century by William Fitz Robert the second Earl of Gloucester as a market town, Petersfield grew in importance because of its location on a direct route north to London and south to the coast. Like those travelers before us we took advantage of the locale returning most days to a late meal and a pint at the pub. Albeit we had the benefit of modern travel and Brit Rail passes purchased before leaving Canada which offered us sizeable fare savings.

Rising the next morning to very un-English like weather ( read “sunny” ) the three of us headed for Petersfield, south of London. During our stay this would be our home away from home. Founded in the 12th century by William Fitz Robert the second Earl of Gloucester as a market town, Petersfield grew in importance because of its location on a direct route north to London and south to the coast. Like those travelers before us we took advantage of the locale returning most days to a late meal and a pint at the pub. Albeit we had the benefit of modern travel and Brit Rail passes purchased before leaving Canada which offered us sizeable fare savings. A short visit can’t do justice to all that York offers but the highlights of our visit include Jorvik on the site of a Viking village complete with its workshops to latrines. The Shambles, a medieval street were butchers dressed and displayed their wares. Thomas Herbert House on the site of a Lord Mayor of London Christopher Herbert’s house of 1620. Could I be related? Of course the Ghost Walk, an entertaining stroll through after hours York and a great way to learn the town’s darker history followed by a glass of the local bitters and Cornish pasties at the Golden Fleece Pub. Do you sense a bedtime ritual? To quickly our stay in York is over and we board the return train to Petersfield. Our next excursion, Windsor.

A short visit can’t do justice to all that York offers but the highlights of our visit include Jorvik on the site of a Viking village complete with its workshops to latrines. The Shambles, a medieval street were butchers dressed and displayed their wares. Thomas Herbert House on the site of a Lord Mayor of London Christopher Herbert’s house of 1620. Could I be related? Of course the Ghost Walk, an entertaining stroll through after hours York and a great way to learn the town’s darker history followed by a glass of the local bitters and Cornish pasties at the Golden Fleece Pub. Do you sense a bedtime ritual? To quickly our stay in York is over and we board the return train to Petersfield. Our next excursion, Windsor.

During my walk-about I meandered down narrow roads, past Market Cross House which is said to have a secret passage way used by King Charles II for private trysts. Continuing through public and some private gardens. After a lengthy stroll along the Thames I found myself at Eton College where since 1440 A.D. Olde Blighty’s future leaders have been educated. A quick check of my watch and I realize that I have barely enough time for a fly-by sandwich and an Ale at the Bel and The Dragon before I am to meet up with the women.

During my walk-about I meandered down narrow roads, past Market Cross House which is said to have a secret passage way used by King Charles II for private trysts. Continuing through public and some private gardens. After a lengthy stroll along the Thames I found myself at Eton College where since 1440 A.D. Olde Blighty’s future leaders have been educated. A quick check of my watch and I realize that I have barely enough time for a fly-by sandwich and an Ale at the Bel and The Dragon before I am to meet up with the women.

Over that ale we decided that London should be next on our agenda even if we could not agree on what to do once there. Fortunately by the time we had arrived at Waterloo Station a compromise had been reached. We spent the day doing the tourist things. Crossing the Thames by the Waterloo Bridge we continued along Victoria Embankment, through the gardens of the same name finding our way to Covent Gardens. There we stopped at Pips Dish before moving on to Trafalgar Square where we took the Tube to Harrods for a little shopping. I vowed that my next time in London would be spent in exploration.

Over that ale we decided that London should be next on our agenda even if we could not agree on what to do once there. Fortunately by the time we had arrived at Waterloo Station a compromise had been reached. We spent the day doing the tourist things. Crossing the Thames by the Waterloo Bridge we continued along Victoria Embankment, through the gardens of the same name finding our way to Covent Gardens. There we stopped at Pips Dish before moving on to Trafalgar Square where we took the Tube to Harrods for a little shopping. I vowed that my next time in London would be spent in exploration. Being a fan of Dan Brown‘s The DaVinci Code, locating the Knights of the Templar Church was a must do. As my time in England was rapidly passing I needed to get to it. Some say that the Temple Church is so named for Knights Templar, 12th century pious noblemen who set out to protect pilgrims travelling to the holy land. Others insist the Temple Church was a medieval bribe designed to silence the Knights Templar as they knew a little to much of the Catholic Church’s looting and pillaging of which they played a major role. Likely there is some truth in either version. After following a circuitous route in an effort to find the Temple Church and about to give up I spotted it nestled between much larger buildings in a back alley between London’s Fleet St. and Pump Ct. around the corner from Ye Olde Cock Tavern, fittingly in the centre of a district rife with solicitor’s chambers. Unfortunately, this day the church was closed.

Being a fan of Dan Brown‘s The DaVinci Code, locating the Knights of the Templar Church was a must do. As my time in England was rapidly passing I needed to get to it. Some say that the Temple Church is so named for Knights Templar, 12th century pious noblemen who set out to protect pilgrims travelling to the holy land. Others insist the Temple Church was a medieval bribe designed to silence the Knights Templar as they knew a little to much of the Catholic Church’s looting and pillaging of which they played a major role. Likely there is some truth in either version. After following a circuitous route in an effort to find the Temple Church and about to give up I spotted it nestled between much larger buildings in a back alley between London’s Fleet St. and Pump Ct. around the corner from Ye Olde Cock Tavern, fittingly in the centre of a district rife with solicitor’s chambers. Unfortunately, this day the church was closed.