by Taylore Daniel

Wandering between Hemingway’s two favorite pubs and the hotel he lived in for seven years, it becomes clear that although he traveled extensively, he liked rambling within a small radius when he was in Havana. Both of his regular watering holes were within a five minute walk of his hotel.

Havana itself is a sprawling city of two and a half million or so. Within Havana is La Havana Vieja (Old Havana), a four square kilometer historic district where fabulous architecture, political monuments, broad boulevards, tree-shaded plazas, grand hotels, colonial houses and 1950s vintage cars rule, like Hemingway’s 1955 Chrysler New Yorker convertible. Though in Old Havana, he would’ve had no use for a vehicle. His stomping grounds lay neatly within the parameters of Old Havana, and in fact, his main haunts were all within staggering distance of Calle Obispo.

Obispo itself is one of the liveliest streets in Havana. It’s packed with new and used bookshops, hole-in-the-wall sandwich and pizza kiosks, sugared-churro carts, treed plazas, the smell of cigars and the sounds of Cuban Salsa bands erupting from the bars and restaurants. The first time Hemingway moved to Cuba, in 1932, he settled into Hotel Ambos Mundos, right on the corner of Obispo and Mercaderes.

I decided to mimic Hemingway’s daily route, beginning at his hotel, where he stuck to a strict daily discipline of writing from daybreak until noon or so, followed by, as he summed it up, “Mi mojito en La Bodeguita y mi daiquiri en El Floridita.”

I decided to mimic Hemingway’s daily route, beginning at his hotel, where he stuck to a strict daily discipline of writing from daybreak until noon or so, followed by, as he summed it up, “Mi mojito en La Bodeguita y mi daiquiri en El Floridita.”

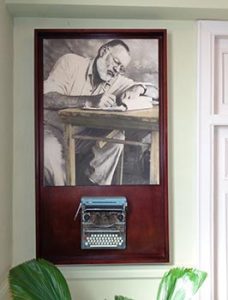

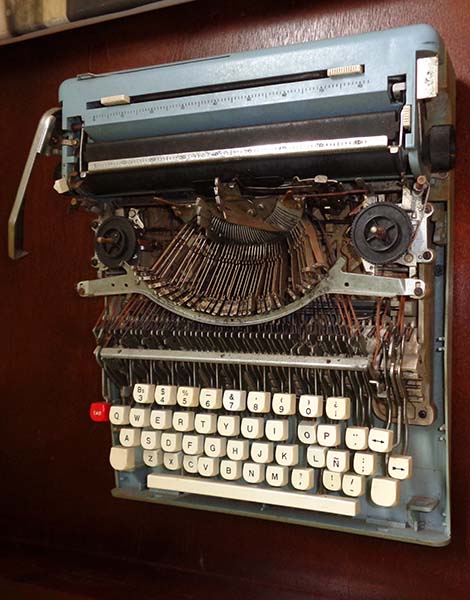

At Hotel Ambos Mundos, where he lived for seven years, I stepped inside a spacious L-shaped lobby. A bar with stools is surrounded by a piano, sofas and tables, and two whole walls are lined by windows. From the polished lobby, a caged elevator clanks up to the 5th floor of the hotel. Off the elevator, a large photo of Hemingway hangs above his black Corona 3 typewriter, a gift to him from his first wife in 1921.

Hemingway’s typewriter! Before computers, before cut-and-paste functions, before auto-correct and spell-check, before email and Word attachments, was the typewriter. Technology wise, it’s like comparing fish larvae to a thrashing, 2,000 pound, adult marlin. There is something innocent and true about it. More than anything else that I saw of Hemingway’s life in Cuba, his typewriter evoked a visceral sense of the man and his life here in Havana.

Hemingway’s typewriter! Before computers, before cut-and-paste functions, before auto-correct and spell-check, before email and Word attachments, was the typewriter. Technology wise, it’s like comparing fish larvae to a thrashing, 2,000 pound, adult marlin. There is something innocent and true about it. More than anything else that I saw of Hemingway’s life in Cuba, his typewriter evoked a visceral sense of the man and his life here in Havana.

Down the hall is room #511, where he lived for seven years, and which is preserved as a museum. In it are a single bed, an entrance table just inside the door, and a desk drenched in sunlight that sits under a window overlooking the streets of Old Havana.

To imagine that he’d sat in this very room, barefoot, unspooling stories onto the page, letter by letter, hunched over the simple black typewriter, was moving. In this very room, on the very typewriter mounted on the wall outside, he began “For Whom The Bell Tolls” about the Spanish Civil War. To imagine this robust sportsman and adventurer sitting quietly, diligently pecking out his stories, conjures up the contrasts within this man. Though even in his writing, he had the spirit of a hunter, equating his old typewriter—with its demands for hard strikes upon each key—as his “Royal Machine Gun.”

Just as Hemingway would leave his typewriter after a morning of writing to head into an afternoon and evening of drinking, it was now time to leave his hotel and check out his favorite watering holes.

Heading just two short blocks from the hotel is Calle Empedrado. Turn left and one block up is one of Hemingway’s two favorite afternoon drinking establishments, La Bodeguita del Medio, which perfected Cuba’s national drink, the mojito.

Before I could even see the sign for this bar, I was struck by a mass of people spilling in and out its doors, loud jazz coming from a band within. Inside, it was standing room only between packed tables and bar stools, the bartender lining up a row of mojitos, which Hemingway declared were the best in Havana. Having tried a mojito that tasted like nothing more than sugar-water in another (unnamed bar) before settling in at the Bodeguita, I can personally attest to the Bodeguita as having perfected this blend of rum, fresh-squeezed lime, sugar, soda, ice and a type of mint called yerba buena.

From La Bodeguita, it was a short jaunt back to Calle Obispo, then up seven blocks to Hemingway’s other favorite watering hole, El Floridita Bar, just across from Museo de Bellas Artes. Here, they named a drink for Hemingway called “papa dobles,” which consists of rum, freshly squeezed pink grapefruit juice and lime juice, maraschino liqueur and sugar syrup all shaken together with ice, then strained into a chilled martini glass. Hemingway clearly spent a lot of time here, evidenced by his having a drink named for him.

From La Bodeguita, it was a short jaunt back to Calle Obispo, then up seven blocks to Hemingway’s other favorite watering hole, El Floridita Bar, just across from Museo de Bellas Artes. Here, they named a drink for Hemingway called “papa dobles,” which consists of rum, freshly squeezed pink grapefruit juice and lime juice, maraschino liqueur and sugar syrup all shaken together with ice, then strained into a chilled martini glass. Hemingway clearly spent a lot of time here, evidenced by his having a drink named for him.

His heaviest drinking period, where he spent many a day at El Floridita, occurred when he was writing “The Old Man and the Sea,” which won him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. Though at this time he was living twelve kilometers outside of Havana at his Finca Vigia, cajoled away from Old Havana by his third wife. He lived at the finca from 1939 until 1960, and entertained guests from Gary Cooper, Errol Flynn and Spencer Tracy, to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

His love of Old Havana, and of Cuba, was evident in the gift of his Nobel Prize medal to the Cuban people. Though Hemingway is now long gone, his energy and complex genius still thrum through the vibrant streets of La Havana Vieja, adding a poignant note of a life fully lived to this sensual Caribbean island. This lively Cuban bar in the heart of Old Havana was one of Hemingway’s favorite haunts.

If You Go:

Money: Two currencies exist side by side, the Convertible peso and the regular Cuban peso. The convertible peso is considered “tourist money” and is worth considerably more than the non-convertible bills. Always check, if you pay with a convertible peso, that your change comes in convertible pesos. The word “convertible” will be written right on the bill.

Hotels and Casas Particulares: Book as early as you can. There are not a lot of accommodations available in Old Havana, and I’d highly recommend you book a place right in the old town. Just a street or two beyond it, the neighborhoods have narrow, often unlit roads, which are not recommended at night, and have been known to have problems with muggings even in the daytime.

Hop-On Hop-Off Bus: Highly recommend! For a mere 10 CUC (pronounced ‘kook’), you’ll be taken down Paseo de Marti, along the Malecon, over to the Plaza de la Revolucion, to the Copacabana nightclub, through Vedado and much more. A terrific, effortless way to get an overview of greater Havana.

About the author:

Taylore Daniel B.A. has traveled through thirty countries, and is a writer, artist and speaker. Her upcoming book is “Travel and Retire Abroad,” and she will soon be re-releasing “Spain to Egypt: A Grand Tour Around the Cradle of Western Civilization.” Visit her at www.tayloredaniel.com

All photos are by Taylore Daniel

We enter a thatched tobacco aging hut to learn about the process of growing, preparing and marketing the harvest. Each farmer is given a quota, with ninety percent of the crop being bought by the government. The farmer retains the final ten percent and is free to use it for personal consumption, local sales and exchanges or making and selling cigars to tourists. Our group gathers around our host farmer and settles in to hear firsthand about his working life.

We enter a thatched tobacco aging hut to learn about the process of growing, preparing and marketing the harvest. Each farmer is given a quota, with ninety percent of the crop being bought by the government. The farmer retains the final ten percent and is free to use it for personal consumption, local sales and exchanges or making and selling cigars to tourists. Our group gathers around our host farmer and settles in to hear firsthand about his working life. However, every farmer puts his own unique stamp on the tobacco he gets to keep, by fermenting it according to an individual recipe. These are often passed down for generations. Our guide’s family recipe was fairly simple, calling only for water, vanilla and rum. But the farm host’s recipe was a bit more elaborate, and includes “water, pineapple skin, guava leaves, honey, sugar cane and a little rum.” With a sly smile on his face, our host notes that some of that rum is applied to the outside of the leaves, and some to the inside of the farmer.

However, every farmer puts his own unique stamp on the tobacco he gets to keep, by fermenting it according to an individual recipe. These are often passed down for generations. Our guide’s family recipe was fairly simple, calling only for water, vanilla and rum. But the farm host’s recipe was a bit more elaborate, and includes “water, pineapple skin, guava leaves, honey, sugar cane and a little rum.” With a sly smile on his face, our host notes that some of that rum is applied to the outside of the leaves, and some to the inside of the farmer. After our farmer finishes his demonstration, he lights up an aged cigar. Others are passed around for us to try, and I relish watching my fellow travelers’ reactions. I end up enjoying most of the tobacco in our Cuban Adventures group, as the others didn’t want more than a couple of puffs. Their loss was definitely my gain, for the smoke is robust and the taste smooth with a hint of honey.

After our farmer finishes his demonstration, he lights up an aged cigar. Others are passed around for us to try, and I relish watching my fellow travelers’ reactions. I end up enjoying most of the tobacco in our Cuban Adventures group, as the others didn’t want more than a couple of puffs. Their loss was definitely my gain, for the smoke is robust and the taste smooth with a hint of honey.

As I let the smoke caress the inside of my mouth, I look out into the valley and into the tobacco fields below. This has been one of the essential experiences I wanted to have in Cuba and I have enjoyed every minute of it. Like our host’s recipe for fermenting tobacco, the magic came from a variety of ingredients, all blended in the right proportions: rich tobacco, fresh mountain air, a relaxed pace of life, friendly and welcoming residents and the local organic produce. The combination captured me; I didn’t want to leave Viñales, and I certainly plan to go back.

As I let the smoke caress the inside of my mouth, I look out into the valley and into the tobacco fields below. This has been one of the essential experiences I wanted to have in Cuba and I have enjoyed every minute of it. Like our host’s recipe for fermenting tobacco, the magic came from a variety of ingredients, all blended in the right proportions: rich tobacco, fresh mountain air, a relaxed pace of life, friendly and welcoming residents and the local organic produce. The combination captured me; I didn’t want to leave Viñales, and I certainly plan to go back.

We arrived in town after a 300 km trip from Havana on our big blue and white Viazul bus. As we pulled in to the downtown bus depot we saw the usual crowd of locals there with large placards and photos, touting the virtues of their various casa particulars. While it was a tough call whether or not we should stay at any one of the hundreds of private residences, we opted this time to head out to the nearby Peninsula de Ancón, where the first new resorts were developed in Cuba following the 1959 revolution.

We arrived in town after a 300 km trip from Havana on our big blue and white Viazul bus. As we pulled in to the downtown bus depot we saw the usual crowd of locals there with large placards and photos, touting the virtues of their various casa particulars. While it was a tough call whether or not we should stay at any one of the hundreds of private residences, we opted this time to head out to the nearby Peninsula de Ancón, where the first new resorts were developed in Cuba following the 1959 revolution. The Ancón Hotel is nothing to look at, featuring typical Russian-style architecture from the 1980s. It is fairly well-appointed inside and all-inclusivo (all food and drink included). Ask to stay in the newer part. The main dining room is where to turn up for the big buffet-style meals, and you can get nourishment anytime at an outdoor snack bar. The food is adequate but not exceptional. The old saying that ‘You don’t go to Cuba for the food’ still holds true, although things are improving as they realize the importance of the tourist peso. Like every tourist hotel, there are nightly shows at a stage near the outdoor bar, featuring a great array of talent. It makes one appreciate the high level of training for young musicians, singers and dancers in Cuba. The best feature was the Playa Ancón itself, with wide expanses of white sand and beautiful blue ocean for sunbathing, swimming, skin diving, boat trips and fishing.

The Ancón Hotel is nothing to look at, featuring typical Russian-style architecture from the 1980s. It is fairly well-appointed inside and all-inclusivo (all food and drink included). Ask to stay in the newer part. The main dining room is where to turn up for the big buffet-style meals, and you can get nourishment anytime at an outdoor snack bar. The food is adequate but not exceptional. The old saying that ‘You don’t go to Cuba for the food’ still holds true, although things are improving as they realize the importance of the tourist peso. Like every tourist hotel, there are nightly shows at a stage near the outdoor bar, featuring a great array of talent. It makes one appreciate the high level of training for young musicians, singers and dancers in Cuba. The best feature was the Playa Ancón itself, with wide expanses of white sand and beautiful blue ocean for sunbathing, swimming, skin diving, boat trips and fishing. If you get tired of the beach life, it’s only necessary to hop into a cute little yellow coco cab and you’ll be in town in 10 minutes. There’s a lot to see in Trinidad: perfectly preserved churches, museums that were palaces and tenement houses that are a symbol of that Cuban region for its peculiar style. The old town architecture is neo-classical and baroque, with a Moorish flavour. Red tile roofed houses painted with pastel colors, ornamented with artistic balconies, iron wrought railings and multicolour facades. The city is very clean and well cared for. If you walk over the cobbled streets of the Trinidad, it makes you feel like going back into colonial times. A friend remarked to me that the millions of stones came from the bilges of Spanish galleons that dumped their ballast in the city and replaced it with the plunder of the new world. I wasn’t able to verify that story anywhere, but it seems possible.

If you get tired of the beach life, it’s only necessary to hop into a cute little yellow coco cab and you’ll be in town in 10 minutes. There’s a lot to see in Trinidad: perfectly preserved churches, museums that were palaces and tenement houses that are a symbol of that Cuban region for its peculiar style. The old town architecture is neo-classical and baroque, with a Moorish flavour. Red tile roofed houses painted with pastel colors, ornamented with artistic balconies, iron wrought railings and multicolour facades. The city is very clean and well cared for. If you walk over the cobbled streets of the Trinidad, it makes you feel like going back into colonial times. A friend remarked to me that the millions of stones came from the bilges of Spanish galleons that dumped their ballast in the city and replaced it with the plunder of the new world. I wasn’t able to verify that story anywhere, but it seems possible. The Plaza Mayor is considered the epicentre of all things, and the eager traveller should start their walking tour there. Make your first stop the Iglesia Parroquial de la Santísima Trinidad (Church of the Holy Trinity), at the upper edge of the plaza. The city’s main church is also Cuba’s oldest. Although there has been a church on the site since 1620, construction began on the current building was completed in 1892. The interior with its 14 alters is breathtaking. A small donation is customary.

The Plaza Mayor is considered the epicentre of all things, and the eager traveller should start their walking tour there. Make your first stop the Iglesia Parroquial de la Santísima Trinidad (Church of the Holy Trinity), at the upper edge of the plaza. The city’s main church is also Cuba’s oldest. Although there has been a church on the site since 1620, construction began on the current building was completed in 1892. The interior with its 14 alters is breathtaking. A small donation is customary. If you are into la mùsica as much as we are, there are lots of great venues de la noche to choose from.

If you are into la mùsica as much as we are, there are lots of great venues de la noche to choose from. Another real find was the Palenque de los Congos Reales. This fabulous open-air nightclub specializes in performances of relatively authentic Afro-Cuban dance and music. You can always catch something spectacular there, performed by a large company of dancers, and accompanied by a big band of hot players.

Another real find was the Palenque de los Congos Reales. This fabulous open-air nightclub specializes in performances of relatively authentic Afro-Cuban dance and music. You can always catch something spectacular there, performed by a large company of dancers, and accompanied by a big band of hot players. As in all of Cuba, paladars are plentiful in Trinidad. These officially authorized restaurants in people’s homes quite often serve tastier food than you can find in any of the state run restaurants. Our favourite was the Paladar Estela. It’s hardly a secret – you can find it near the top of the list in all the guide books. You enter through an elaborately decorated colonial house with many religious objects, two blocks north of the cathedral. The handful of tables are set in an exuberant backyard garden setting, with huge numbers of flowering plants and a wall festooned with vines. Portions are nearly as voluminous as the plant life, and dishes include roast pork a la cubana, fried chicken, grilled fish, and ham omelette.

As in all of Cuba, paladars are plentiful in Trinidad. These officially authorized restaurants in people’s homes quite often serve tastier food than you can find in any of the state run restaurants. Our favourite was the Paladar Estela. It’s hardly a secret – you can find it near the top of the list in all the guide books. You enter through an elaborately decorated colonial house with many religious objects, two blocks north of the cathedral. The handful of tables are set in an exuberant backyard garden setting, with huge numbers of flowering plants and a wall festooned with vines. Portions are nearly as voluminous as the plant life, and dishes include roast pork a la cubana, fried chicken, grilled fish, and ham omelette. There’s a lot to see outside the city too. Be sure to make time for a trip to the Valle de los Ingenios (Valley of the Sugar Mills) to see the ruins of dozens of 19th century sugar mills located just outside the city, which are a reminder of the importance of sugar to the Cuban economy over the centuries. Other attractions include hiking in the surrounding mountains and horseback riding in the beautiful countryside.

There’s a lot to see outside the city too. Be sure to make time for a trip to the Valle de los Ingenios (Valley of the Sugar Mills) to see the ruins of dozens of 19th century sugar mills located just outside the city, which are a reminder of the importance of sugar to the Cuban economy over the centuries. Other attractions include hiking in the surrounding mountains and horseback riding in the beautiful countryside.

Arriving in Havana leaves even my cynical and spoiled travel mind agape. I am staying in Casco Viejo, Havana’s old town, once home to rich sugar barons and real American gangsters. The elaborate mansions built by these once-residents of Havana remain. They are dilapidated, crumbling but nonetheless majestic, echoing their former glory, like grand old dames whose jewellery has lost its gemstones and once fine clothing has become threadbare and moth-eaten.

Arriving in Havana leaves even my cynical and spoiled travel mind agape. I am staying in Casco Viejo, Havana’s old town, once home to rich sugar barons and real American gangsters. The elaborate mansions built by these once-residents of Havana remain. They are dilapidated, crumbling but nonetheless majestic, echoing their former glory, like grand old dames whose jewellery has lost its gemstones and once fine clothing has become threadbare and moth-eaten.

If your Spanish is up to it, or if you are lucky enough to find an English speaker somewhere along the way, it is fascinating to engage in conversation with a local, to get their take on their everyday life, their current political situation and Cuba’s fascinating past.

If your Spanish is up to it, or if you are lucky enough to find an English speaker somewhere along the way, it is fascinating to engage in conversation with a local, to get their take on their everyday life, their current political situation and Cuba’s fascinating past. Undertones of the communist regime run throughout Havana. Some are obvious – the lines of people waiting outside the bakery to have their ration cards filled, the women approaching you on the street asking for soap or lip balm and the bare-as-a-baby’s-bottom supermarket shelves. Others you have to delve a little deeper to find – the restrictions placed on television programming, internet usage and travel for Cuban citizens, and the complete absence of any form of advertising (a fact that you may not notice until you return to a capitalist country and are seemingly assaulted with advertising virtually everywhere you look).

Undertones of the communist regime run throughout Havana. Some are obvious – the lines of people waiting outside the bakery to have their ration cards filled, the women approaching you on the street asking for soap or lip balm and the bare-as-a-baby’s-bottom supermarket shelves. Others you have to delve a little deeper to find – the restrictions placed on television programming, internet usage and travel for Cuban citizens, and the complete absence of any form of advertising (a fact that you may not notice until you return to a capitalist country and are seemingly assaulted with advertising virtually everywhere you look).

Surprise! The hype was bigger than reality! While the Cuban cuisine can hardly be described as adventurous, it was a far cry from “No hay!” I now believe there is truth in the maxim: “Tourists first – Cubans last,” but I saw little evidence where luxury goods were involved. Bathroom requisites especially, soap in particular.

Surprise! The hype was bigger than reality! While the Cuban cuisine can hardly be described as adventurous, it was a far cry from “No hay!” I now believe there is truth in the maxim: “Tourists first – Cubans last,” but I saw little evidence where luxury goods were involved. Bathroom requisites especially, soap in particular. The hub of life on the Plaza de la Catedral in the Old Quarter. The square is not large. It could be dropped without trace into most of the Revolutionary Squares which dominate Cuba’s cities and towns. The sixteenth century Cathedral has enormous character, watching over the Plaza like a hen guarding its chicks. These particular chicks are the many stall-holders who, since the communist relax, have been allowed to take on ”private enterprise” schemes [largely souvenir stalls] in an effort to aid the economy. Each stall his its own brightly coloured awning so that viewing the Square form the Cathedral steps in the dazzling light sunlight presents a feeling of looking into an emerald casket.

The hub of life on the Plaza de la Catedral in the Old Quarter. The square is not large. It could be dropped without trace into most of the Revolutionary Squares which dominate Cuba’s cities and towns. The sixteenth century Cathedral has enormous character, watching over the Plaza like a hen guarding its chicks. These particular chicks are the many stall-holders who, since the communist relax, have been allowed to take on ”private enterprise” schemes [largely souvenir stalls] in an effort to aid the economy. Each stall his its own brightly coloured awning so that viewing the Square form the Cathedral steps in the dazzling light sunlight presents a feeling of looking into an emerald casket. Also in the Square, one of Havana’s most exciting Rumba ensembles plays throughout the day at El Patio. An exciting feat for a local Cuban band that send revelers when it munched Portuguese lyrics with our English lyrics when we took together on stage in the evening.

Also in the Square, one of Havana’s most exciting Rumba ensembles plays throughout the day at El Patio. An exciting feat for a local Cuban band that send revelers when it munched Portuguese lyrics with our English lyrics when we took together on stage in the evening. Certainly, there is a fair number of decaying crumbling once-elegant buildings. But Havana is well into a vast renovation program, thanks to the World Heritage Site claim stamped on the city by UNESCO.

Certainly, there is a fair number of decaying crumbling once-elegant buildings. But Havana is well into a vast renovation program, thanks to the World Heritage Site claim stamped on the city by UNESCO. here is little evidence of Cuba’s legendary former Head of State, Fidel Castro. Far more in evidence, especially in Havana, are tributes to the American writer Ernest Hemingway who lived in the capital for over twenty years. There are statues and plaques in his honour all over the city. His house is now an intriguing Museum, almost like a shrine. Across the city, many of the writer’s ole haunts and watering holes still proudly bear his name. There is even a hotel named after his novel, El Viejo y el Mar [The Old Man and the Sea] where we stayed for several nights. Prices ere quite reasonable – but still beyond the average Cuban’s income.

here is little evidence of Cuba’s legendary former Head of State, Fidel Castro. Far more in evidence, especially in Havana, are tributes to the American writer Ernest Hemingway who lived in the capital for over twenty years. There are statues and plaques in his honour all over the city. His house is now an intriguing Museum, almost like a shrine. Across the city, many of the writer’s ole haunts and watering holes still proudly bear his name. There is even a hotel named after his novel, El Viejo y el Mar [The Old Man and the Sea] where we stayed for several nights. Prices ere quite reasonable – but still beyond the average Cuban’s income.