by W. Ruth Kozak

Along with a small group of other travelers I board a cruise ship at Aswan, Egypt to sail down the Nile on an adventure that will take me to visit various archaeological sites. For me this journey is like a dream come true. An avid arm-chair archeologist and historical fiction writer, I have always wanted to visit Egypt. Now here I am on the deck of a cruise ship, sailing down the mighty Nile River.

The Nile River is the world’s longest river, flowing through eleven countries approximate 4,665 miles out of the heart of Africa, northward to the Mediterranean Sea. There are two sources: The White Nile in equatorial Africa rises from the Great Lake region of central Africa is the headwater. The Blue Nile begins in Ethiopia and flows into Sudan. The two rivers meet at Khartoum. The north section flows mostly through desert from Sudan to Egypt ending at a large delta that empties into the Mediterranean Sea. The cataracts are a progression of white rapids form the southern border of Egypt at Sudan. The First Cataract is at Aswan.

Cruising Down the Nile

Past Aswan, the great Nile Valley begins. Limestone cliffs run parallel along the shore for more than 400 miles, reach out toward the desert. As my travel companions and I lounge on the upper deck in the warm March sunshine, I watch the shoreline slip by. It is remarkable how quiet it is, as if the ship is sliding with the current, the pastoral shores passing by as if in a silent movie. In the reedy marshes egrets, ducks and geese nest. The Nile was known to nurture the sacred lotus, reeds and papyrus plants that were later used as writing paper. The ancient Egyptians called the river the “Father of Life” or “Mother of all men”. They called it Hap-Ur or Great Hap after the god Hapi, a divine spirit that blessed the land with rich silt deposits. The Nile is Egypt’s life-blood.

From the deck, I watch a parade of turbaned Nubian farmers dressed in traditional long cotton gelabbas as they lead donkeys laden with cut sugar-cane and reeds along the palm-shaded paths beside the shore. Young farm boys on ponies trot by the river bank and herds of goats and cattle graze in the marsh-land at the river’s edge.

Will I see a Crocodile?

As I sit on the deck watching the river flow by I am reminded of a children’s song that keeps running through my head …

Oh she

sailed away on a

pleasant summer’s day

on the back of a crocodile.You see, said she, “He’s as

tame as he can be,

I’ll float him down the Nile.”But the

croc’ winked his eye as she

waved to all good-bye,

wearing a sunny smile.At the

end of the ride the

lady was inside, and the

smile on the crocodile!

I wonder if there are crocodiles lurking in the river. I peer into the dark green water hoping to spot one. The Nile crocodile is the second largest reptile in the world, after the salt-water crocodile. They grow to up to 5 meters (16 ft) in length and weigh up to 410 kg (900 lbs). The largest on record was 61 meters (20 ft) and weighed 900 Kg (2,000 lbs). Their powerful bite and sharp conical teeth grip so firmly it is almost impossible to loosen. They are aggressive predators and will lay in wait for days waiting for the suitable moment to attack. It isn’t easy to escape. Crocodiles have been known to gallop at speeds of about 50 kilmetres (30 miles) an hour!

I wonder if there are crocodiles lurking in the river. I peer into the dark green water hoping to spot one. The Nile crocodile is the second largest reptile in the world, after the salt-water crocodile. They grow to up to 5 meters (16 ft) in length and weigh up to 410 kg (900 lbs). The largest on record was 61 meters (20 ft) and weighed 900 Kg (2,000 lbs). Their powerful bite and sharp conical teeth grip so firmly it is almost impossible to loosen. They are aggressive predators and will lay in wait for days waiting for the suitable moment to attack. It isn’t easy to escape. Crocodiles have been known to gallop at speeds of about 50 kilmetres (30 miles) an hour!

The Nile crocodile is known to attack people as well as animals. Up to 200 people a year die from crocodile encounters. I wonder, as I watch the grazing herds and passing parade of Egyptians on the shore if there might be crocodiles lying in wait for a noon-day meal.

I ask Hanan, the Egyptologist who accompanies our group, if these vicious reptiles might be lurking in the shallows. “Since the building of the Aswan Dam in 1960, the crocodiles now reside on the south side of Lake Nasser,” she assures me. I also learn that between the 1940’s and ‘60s the crocodiles were hunted for their high quality leather and this has depleted them.

Even though Hanan said there were no crocodiles in that part of the river, I keep watching in the hopes I might spot one. It isn’t until we reach Kom Ombo that, to my surprise, I discover a temple room full of them!

The Kom Ombo Temples

Kom Ombo is a small city once situated at the crossroads between the caravan route from Nubia and the routes from the gold mines in the eastern Sahara. During the reign of Ptolemy VI (180-145 BC) it was a training depot for African war elephants. Today Kom Ombo is the home of many Nubians who were displaced after the Aswan Dam flooded their lands.

Kom Ombo is a small city once situated at the crossroads between the caravan route from Nubia and the routes from the gold mines in the eastern Sahara. During the reign of Ptolemy VI (180-145 BC) it was a training depot for African war elephants. Today Kom Ombo is the home of many Nubians who were displaced after the Aswan Dam flooded their lands.

In ancient times, this part of the Nile River was known for the crocodiles that basked along the shore posing a threat to the locals. This is likely why one of the temples at Kom Ombo is dedicated to Sobek, the crocodile god.

The crocodile was an important symbol in ancient Egypt, both feared and revered. It was worshipped as a crocodile-headed god named Sobek. Several ancient tombs have been discovered with hieroglyphics showing a crocodile snatching a baby hippopotamus as it emerged from its mother during birth. Hippos were the only creature in the Nile who was more powerful than the crocodiles. Other tomb scenes show crocodiles mating. Sometimes they were kept in temple pools where they were fed, covered with jewelry and worshipped. When the crocodiles died, they were embalmed, mummified, placed in sarcophagi and buried in sacred tombs.

At Kom Ombo, the Egyptologist, Hanan, leads us to the archaeological site. Kom Ombo Temple is a double temple built during the Ptolemaic dynasty. It has courts, halls, sanctuaries and rooms dedicated to two sets of gods. On the right side is a temple to Sobek-Re, the crocodile god combined with the sun god Re. Sobek is associated with Set, the murderer of Osiris and enemy of Horus. In the myth, Set changed himself into a crocodile to escape Osiris wrath. The ancient Egyptians believed if they honored the crocodile as a god they would be safe from attacks by the ferocious creatures.

Sobek was an aggressive deity like the violent Nile crocodile. Yet, in spite of this, Sobek became known for his benevolence after associating with Isis as a healer of Osiris following his violent murder by Set. The name Sobek has been translated to mean “he who unites the dismembered limbs of Osiris.” He was considered a protective deity by the Egyptians. His fierceness warded off evil while defending the innocent. He was associated with pharaonic power, military prowess and fertility and in particular invoked protection against the dangers of the Nile River. For this reason the crocodile was deified and worshipped.

We enter through the remains of a monumental gate. Much of the temple has been washed away by Nile floods so only low walls and stumps of pillars in the forecourt remain. In the beautiful Outer Hypsostyle Hall, fifteen sturdy columns stand with decorated cornices and carved winged sun disk.

The left side of the temple is dedicated to the falcon god Haroeris “The Good Doctor” along with his consort Ta-Sent-Nefer, “The Good Sister. Hanan ushers us through and interprets the stories of the hieroglyphics carved on the pillars and walls. On one wall is a relief of Sobek in his snake form. Another shows Ptolemy II making offerings to various gods. On the rear wall Hanan points out a hieroglyph representing a set of surgical instruments probably carved during the Roman period.

Mummified Crocodiles!

Finally, we enter a large room that, to my surprise, is full of crocodiles! Mummified crocodiles! It is evident from the large number displayed here that the crocodile was held in honor by the people of Kom Ombo. The museum contains crocodile eggs as well as mummified baby and adult crocodiles. Some of the mummies were found with babies in their mouths or on their backs. These ferocious beasts are known to care diligently for their young, often carrying them on their backs. By preserving them by mummification it emphasized the protective and nurturing aspects of Sobek as he protected the Egyptian people just as the crocodile protects its young.

Finally, we enter a large room that, to my surprise, is full of crocodiles! Mummified crocodiles! It is evident from the large number displayed here that the crocodile was held in honor by the people of Kom Ombo. The museum contains crocodile eggs as well as mummified baby and adult crocodiles. Some of the mummies were found with babies in their mouths or on their backs. These ferocious beasts are known to care diligently for their young, often carrying them on their backs. By preserving them by mummification it emphasized the protective and nurturing aspects of Sobek as he protected the Egyptian people just as the crocodile protects its young.

I didn’t see any live crocodiles that day, but I learned so much about the ancient Egyptians and got a new understanding of why this fierce predatory animal gained such prominence and was held in honor by the people of Kom Ombo.

Private Day Tour Excursion To Edfu and Kom Ombo

If You Go:

♦ Kom Ombo Temple site Kom Ombo is 45 miles north of Aswan. The temple site is 4 kms from the town.

♦ Nile Cruise: I boarded the Sonesta Star Goddess at Aswan for my cruise down the Nile. This is a five-star all-suite cruise ship and the cruise lasted for 3 days between Aswan and Luxor. It included daily guided excursions with an Egyptologist guide. See http://www.Sonesta.com/nilecruises

♦ Everything you need to know about Nile Crocodiles, They are the largest species of crocodiles in Africa. They grow to about 6 metres long and can weight over 700 kgs. They almost became extinct in the 20th century and are now a protected species. Nile crocodiles are carnivores. They eat fish but prey on animals and are known to attack humans.

5-Day Nile Cruise: Luxor, Aswan, Kom-Ombo, Edfu from Cairo

About the author:

Ruth Kozak was thrilled to be invited to Egypt by Egyptian Tourism to write stories about this amazing country. She really did look for crocodiles along the Nile and was disappointed not so see any live ones! Ruth is both a travel journalist and historical fiction author. She is the author of: SHADOW OF THE LION: THE FIELDS OF HADES. Her first novel SHADOW OF THE LION: BLOOD ON THE MOON (volume one of two, a story of the fall of Alexander the Great’s dynasty) was published this summer by www.mediaaria-cdm.com at exactly the same time the fabled tomb at Amphipolis was uncovered. It is available on www.amazon.com or can be ordered through book stores.

Photo credits:

Crocodile by Glen Carrie on Unsplash

Photos of the Kom Ombo Temple site by W. Ruth Kozak.

The first thing I noticed as we drove in Cairo from the airport, were the miles and miles of densely built apartment blocks, many of them half-finished stretching out from the Nile as far as you could see. Laundry fluttered from some of the balcony but there were just as many that appeared empty. The Egyptologist with our group of Canadian travel writers explained that this was part of the reasons for the first revolution – the overbuilding on green space, a corruption.

The first thing I noticed as we drove in Cairo from the airport, were the miles and miles of densely built apartment blocks, many of them half-finished stretching out from the Nile as far as you could see. Laundry fluttered from some of the balcony but there were just as many that appeared empty. The Egyptologist with our group of Canadian travel writers explained that this was part of the reasons for the first revolution – the overbuilding on green space, a corruption. As a female solo traveler, I would not want to venture alone to Cairo, although I’d certainly not hesitate to return to this marvelous country in the company of a tour group. Did I feel any danger in Cairo? In spite of the two revolutions and the pending elections at the time I was there, and the spate of unfavorable media coverage about Egypt, travel warnings from embassies, that has diminished their tourism by 90%, I felt no sense of danger. In fact, there was good security in place everywhere. And what impressed me so much was the people. I have never met such gracious, generous, friendly people anywhere before. Young, old, men, women and children approached me and my travel companions on the street with smiles. “Welcome! Where are you from? Welcome to Egypt!” These are proud people, open and friendly, who walk with a noble stance, proud of their country and heritage and greet you with welcoming smiles.

As a female solo traveler, I would not want to venture alone to Cairo, although I’d certainly not hesitate to return to this marvelous country in the company of a tour group. Did I feel any danger in Cairo? In spite of the two revolutions and the pending elections at the time I was there, and the spate of unfavorable media coverage about Egypt, travel warnings from embassies, that has diminished their tourism by 90%, I felt no sense of danger. In fact, there was good security in place everywhere. And what impressed me so much was the people. I have never met such gracious, generous, friendly people anywhere before. Young, old, men, women and children approached me and my travel companions on the street with smiles. “Welcome! Where are you from? Welcome to Egypt!” These are proud people, open and friendly, who walk with a noble stance, proud of their country and heritage and greet you with welcoming smiles. One of the main interest for me was the Egyptian Museum located right near Tahrir Square. The museum contains the world’s most extensive collection of pharanoiac antiquities. I saw the King Tut exhibit when it was in Seattle but those treasures were insignificant compared to what you will see on display here: magnificent golden chariots, precious jewelry, and countless other incredible treasures as well as coffins, mummies and other artifacts from prehistoric through the Roman periods The museum houses approximately 160,00 objects in total. I was told they plan to build a new museum so that more of the treasures can be displayed.

One of the main interest for me was the Egyptian Museum located right near Tahrir Square. The museum contains the world’s most extensive collection of pharanoiac antiquities. I saw the King Tut exhibit when it was in Seattle but those treasures were insignificant compared to what you will see on display here: magnificent golden chariots, precious jewelry, and countless other incredible treasures as well as coffins, mummies and other artifacts from prehistoric through the Roman periods The museum houses approximately 160,00 objects in total. I was told they plan to build a new museum so that more of the treasures can be displayed. In Old Cairo we visited several churches including the oldest Greek Orthodox Church and the Ben Ezra Synagogue which dates from the 9th century and is the oldest Jewish place of worship in Egypt. We also visited the 4th century Hanging Church which is built on the bastions of the ancient Roman wall and ‘suspended’ above the level of the Nile. In one of the oldest Coptic churches in Egypt we entered the crypt-like area below where there is a small room that is supposed to have been where Mary and Joseph and the baby Jesus found shelter when they fled to Egypt. Old Cairo also had an excellent bazaar for buying souvenirs, some very expensive and others modestly priced including furniture and jewelry.

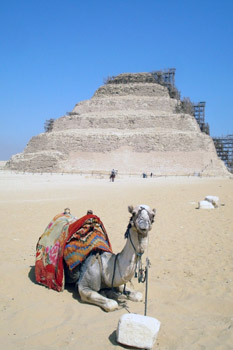

In Old Cairo we visited several churches including the oldest Greek Orthodox Church and the Ben Ezra Synagogue which dates from the 9th century and is the oldest Jewish place of worship in Egypt. We also visited the 4th century Hanging Church which is built on the bastions of the ancient Roman wall and ‘suspended’ above the level of the Nile. In one of the oldest Coptic churches in Egypt we entered the crypt-like area below where there is a small room that is supposed to have been where Mary and Joseph and the baby Jesus found shelter when they fled to Egypt. Old Cairo also had an excellent bazaar for buying souvenirs, some very expensive and others modestly priced including furniture and jewelry. Giza is located to the west of Central Cairo not far from the ancient cities of Memphis and Saqqara. The pyramids include the great pyramid built for the pharaoh Cheops in the 4th dynasty and the slightly smaller Pyramid of Chephren date from around 2500 BC. There are also the Pyramid of Mykerinos and some smaller pyramids built for the kings’ families, The Great Pyramid of Cheops immortalizes the son of Snerferu and Hetpheres. This pyramid is the largest of the three, comprised of 2.3 million stone blocks each weighing an average of 2.5 tons. How on earth did they move these stones to build a monument so high as this? This is definitely one of the ‘wonders’ of the world! In fact, the pyramids of Giza are the last remaining Seven Wonders of the World.

Giza is located to the west of Central Cairo not far from the ancient cities of Memphis and Saqqara. The pyramids include the great pyramid built for the pharaoh Cheops in the 4th dynasty and the slightly smaller Pyramid of Chephren date from around 2500 BC. There are also the Pyramid of Mykerinos and some smaller pyramids built for the kings’ families, The Great Pyramid of Cheops immortalizes the son of Snerferu and Hetpheres. This pyramid is the largest of the three, comprised of 2.3 million stone blocks each weighing an average of 2.5 tons. How on earth did they move these stones to build a monument so high as this? This is definitely one of the ‘wonders’ of the world! In fact, the pyramids of Giza are the last remaining Seven Wonders of the World. Most of the remnants of ancient Egypt lay scattered on the desert plateau south of Cairo. After visiting the amazing pyramids of Giza we went to see the amazing necropolis at Saqqara and the Step Pyramid of King Djoser. This is the largest necropolis in Egypt, extending for almost five miles. It’s a collection of pyramids, temples and tombs including the Mastaba tombs where the high officials of the Pharaohs were buried.

Most of the remnants of ancient Egypt lay scattered on the desert plateau south of Cairo. After visiting the amazing pyramids of Giza we went to see the amazing necropolis at Saqqara and the Step Pyramid of King Djoser. This is the largest necropolis in Egypt, extending for almost five miles. It’s a collection of pyramids, temples and tombs including the Mastaba tombs where the high officials of the Pharaohs were buried. Farther south, is the ancient royal capital of the pharaohs, Memphis. According to legend it was founded by pharaoh Menes around 3000 BC and was the capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom, remaining an important city throughout history. During the 6th dynasty it was a centre for the worship of Ptah, the god of creation and artworks. There is an alabaster Sphinx guarding the Temple of Ptah that is a memorial of the city’s former power and prestige.

Farther south, is the ancient royal capital of the pharaohs, Memphis. According to legend it was founded by pharaoh Menes around 3000 BC and was the capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom, remaining an important city throughout history. During the 6th dynasty it was a centre for the worship of Ptah, the god of creation and artworks. There is an alabaster Sphinx guarding the Temple of Ptah that is a memorial of the city’s former power and prestige.

Some people will try to tell you that this is not Africa. Morocco, located on the continent’s northwestern edge, is something of an enigma in this regard. Its people are mostly descended from Arab invaders and indigenous Berbers, whose DNA and culture are closer to that of Mediterranean Europe than anything below the Sahara. But when the Gnaoua World Music Festival kicks off every June in Essaouira, on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, its African heart emerges – beating strongly to the rhythms of the drums and three-string basses of the West African slaves who arrived here centuries ago.

Some people will try to tell you that this is not Africa. Morocco, located on the continent’s northwestern edge, is something of an enigma in this regard. Its people are mostly descended from Arab invaders and indigenous Berbers, whose DNA and culture are closer to that of Mediterranean Europe than anything below the Sahara. But when the Gnaoua World Music Festival kicks off every June in Essaouira, on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, its African heart emerges – beating strongly to the rhythms of the drums and three-string basses of the West African slaves who arrived here centuries ago. Gnaoua music is alive and well in Morocco today, though its spiritual origins have been somewhat lost through its own popularity. It’s not just the Sufis who perform Gnaoua music anymore. It’s played in clubs by fusion bands, and on world tours by famous musicians interested in cross-cultural connections. But most significantly, it has become the centerpiece of one of Morocco’s biggest festivals, a four-day event that takes place at the beginning of every summer.

Gnaoua music is alive and well in Morocco today, though its spiritual origins have been somewhat lost through its own popularity. It’s not just the Sufis who perform Gnaoua music anymore. It’s played in clubs by fusion bands, and on world tours by famous musicians interested in cross-cultural connections. But most significantly, it has become the centerpiece of one of Morocco’s biggest festivals, a four-day event that takes place at the beginning of every summer. Some call it the Woodstock of Africa, while others claim it has become too corporate. Founded seventeen years ago, the Gnaoua World Music Festival (known officially by its French name, Le Festival Gnaoua et des musiques du Monde d’Essaouira) attracts over 300,000 people, who not only come to hear Gnaoua music, but also sounds from all over Africa. A lot of the crowd is European, not just hippie-types but also music enthusiasts, wind surfers, and those on cheap breaks. But there are a lot of Moroccans here too, who can afford to come because most of the concerts are free, running late into the night on the town’s beaches.

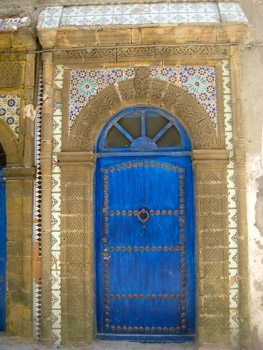

Some call it the Woodstock of Africa, while others claim it has become too corporate. Founded seventeen years ago, the Gnaoua World Music Festival (known officially by its French name, Le Festival Gnaoua et des musiques du Monde d’Essaouira) attracts over 300,000 people, who not only come to hear Gnaoua music, but also sounds from all over Africa. A lot of the crowd is European, not just hippie-types but also music enthusiasts, wind surfers, and those on cheap breaks. But there are a lot of Moroccans here too, who can afford to come because most of the concerts are free, running late into the night on the town’s beaches. Essaouira is known as the windy city, though it bears other names too: the Portuguese, who laid the foundations for the town we see today, called it Mogador, and its Berber name simply means “the wall”. It’s a fortified city with walls that keep out the wind, and also much of modernity. The medina at its centre is labyrinthine and painted almost entirely in white and blue. Gnaoua music permeates the streets, even outside of festival time, and other hallmarks of Moroccan life are there too: traditional hammams (spas), markets, a souk devoted entirely to wood artisans, an old Jewish synagogue (a reminder that Essaouira was once 40% Jewish) and cafés that serve simple, yet delicious fare (always, of course, accompanied by mint tea). These are the best places to eat, especially if you’re on a budget and want to nosh like the locals. Bowls of lentils, spiced with cumin, paprika, and laced with meat, can be bought for as little as 6 dirhams (around 75 cents), and are served with bread, for free. White beans are a similarly delicious bargain, though if you’re feeling a bit more luxurious, fish is the best thing to eat in Essaouira. Kefta, traditional Moroccan meatballs, stuffed with onions and parsley, are delectable too, but sardines, bought fresh from the fishermen down by the beach are even better. Once bought, you can take the fish to a restaurant to be cooked on the spot, often with traditional chermoula sauce (a mixture of cilantro, parsley, chili, lemon, olive oil and spices).

Essaouira is known as the windy city, though it bears other names too: the Portuguese, who laid the foundations for the town we see today, called it Mogador, and its Berber name simply means “the wall”. It’s a fortified city with walls that keep out the wind, and also much of modernity. The medina at its centre is labyrinthine and painted almost entirely in white and blue. Gnaoua music permeates the streets, even outside of festival time, and other hallmarks of Moroccan life are there too: traditional hammams (spas), markets, a souk devoted entirely to wood artisans, an old Jewish synagogue (a reminder that Essaouira was once 40% Jewish) and cafés that serve simple, yet delicious fare (always, of course, accompanied by mint tea). These are the best places to eat, especially if you’re on a budget and want to nosh like the locals. Bowls of lentils, spiced with cumin, paprika, and laced with meat, can be bought for as little as 6 dirhams (around 75 cents), and are served with bread, for free. White beans are a similarly delicious bargain, though if you’re feeling a bit more luxurious, fish is the best thing to eat in Essaouira. Kefta, traditional Moroccan meatballs, stuffed with onions and parsley, are delectable too, but sardines, bought fresh from the fishermen down by the beach are even better. Once bought, you can take the fish to a restaurant to be cooked on the spot, often with traditional chermoula sauce (a mixture of cilantro, parsley, chili, lemon, olive oil and spices). In festival time, the concerts mostly take place on the beaches, but also spill out into the clubs of the new city, located outside the old medina walls. There are events for every taste, though the biggest, most exciting shows happen outdoors on the free stages. Music runs pretty much all night, which not only creates a 24/7 party atmosphere, but also provides a welcome relief to the mid-day temperatures of the Moroccan summer. Essaouira is less hot than Marrakech, thanks to ocean breezes, but high noon temperatures are still nothing to laugh at. The nighttime is cool, perfect weather for dancing to the beats of the Sufi Brotherhoods or visiting world musicians. And dance you will. This is Africa, remember, albeit a much less traditional, more open-minded version of the continent than you might experience elsewhere. Vendors circulate throughout the concert space, selling donuts and other tasty treats. More savory fare can be bought from makeshift stands on the perimeter, selling corn, fish, hard boiled eggs with cumin and salt, and pastries. Alcohol is not obviously easy to procure, but despite what the hustlers might try to tell you (searching for a commission), there are several liquor depots in the new city where you can buy alcohol at a fixed price. It’s very common to see both tourists and locals imbibing on the beach, though usually out of water bottles, often containing the local firewater.

In festival time, the concerts mostly take place on the beaches, but also spill out into the clubs of the new city, located outside the old medina walls. There are events for every taste, though the biggest, most exciting shows happen outdoors on the free stages. Music runs pretty much all night, which not only creates a 24/7 party atmosphere, but also provides a welcome relief to the mid-day temperatures of the Moroccan summer. Essaouira is less hot than Marrakech, thanks to ocean breezes, but high noon temperatures are still nothing to laugh at. The nighttime is cool, perfect weather for dancing to the beats of the Sufi Brotherhoods or visiting world musicians. And dance you will. This is Africa, remember, albeit a much less traditional, more open-minded version of the continent than you might experience elsewhere. Vendors circulate throughout the concert space, selling donuts and other tasty treats. More savory fare can be bought from makeshift stands on the perimeter, selling corn, fish, hard boiled eggs with cumin and salt, and pastries. Alcohol is not obviously easy to procure, but despite what the hustlers might try to tell you (searching for a commission), there are several liquor depots in the new city where you can buy alcohol at a fixed price. It’s very common to see both tourists and locals imbibing on the beach, though usually out of water bottles, often containing the local firewater.

The festival atmosphere pervades the city, and not just at night on the beaches by the big music stages. It’s on the streets in the daytime too, in the official processions of the Gnaoua musicians, and in the unofficial parades of young Moroccan rastas, Spanish girls in harem pants, the old Djellaba-clad (a traditional Moroccan robe) hooked-nose man who haunts the medina and claims to have worked for Cat Stevens, and in the gentle giant dancing manically to the beat of his own drummer. In fact, the festival atmosphere begins the moment you step on the bus to Essaouira. Buses run regularly between Marrakech and the port, and tickets can be bought either directly from the ticket office inside the bus station, or from hustlers outside, who may or may not offer you a better price, albeit probably on a worse bus. But a lower class bus is not a guarantee of a bad experience. In fact, you’re more likely to meet locals that way, locals who, unlike many people you meet on the street, will give you advice for free. Some might recommend a place to stay or eat salty grilled fish, while others will try to convince you of their love for Bob Marley, or may even offer you hashish or wine mixed with cola – both of which maintain various levels of illegality for Moroccans, though each proliferate at the festival. But for most attendees, the music on its own is transcendent enough: beautiful and ancient as it floats above the storied corners of the medina, past the spice sellers and fishing boats, and out to sea.

The festival atmosphere pervades the city, and not just at night on the beaches by the big music stages. It’s on the streets in the daytime too, in the official processions of the Gnaoua musicians, and in the unofficial parades of young Moroccan rastas, Spanish girls in harem pants, the old Djellaba-clad (a traditional Moroccan robe) hooked-nose man who haunts the medina and claims to have worked for Cat Stevens, and in the gentle giant dancing manically to the beat of his own drummer. In fact, the festival atmosphere begins the moment you step on the bus to Essaouira. Buses run regularly between Marrakech and the port, and tickets can be bought either directly from the ticket office inside the bus station, or from hustlers outside, who may or may not offer you a better price, albeit probably on a worse bus. But a lower class bus is not a guarantee of a bad experience. In fact, you’re more likely to meet locals that way, locals who, unlike many people you meet on the street, will give you advice for free. Some might recommend a place to stay or eat salty grilled fish, while others will try to convince you of their love for Bob Marley, or may even offer you hashish or wine mixed with cola – both of which maintain various levels of illegality for Moroccans, though each proliferate at the festival. But for most attendees, the music on its own is transcendent enough: beautiful and ancient as it floats above the storied corners of the medina, past the spice sellers and fishing boats, and out to sea.

Unfortunately we have no time to bargain and buy souvenirs this morning. We’re on our way to board a boat that will take us to visit the island temple of Philae. Hanan, the Egyptologist explains, “These dark-skinned people are Nubians. They live in settlements along the river.” She tells us that because of the lack of tourists due to recent political unrest, these souvenir hawkers and boatmen are struggling to make a living. Hanan points out a settlement of yellow brick houses clustered under a sandy hill across the river. “That is one of their villages. They call it ‘Elephantine’, perhaps because the hill is shaped like an elephant.”

Unfortunately we have no time to bargain and buy souvenirs this morning. We’re on our way to board a boat that will take us to visit the island temple of Philae. Hanan, the Egyptologist explains, “These dark-skinned people are Nubians. They live in settlements along the river.” She tells us that because of the lack of tourists due to recent political unrest, these souvenir hawkers and boatmen are struggling to make a living. Hanan points out a settlement of yellow brick houses clustered under a sandy hill across the river. “That is one of their villages. They call it ‘Elephantine’, perhaps because the hill is shaped like an elephant.” With our handsome young Nubian boatman at the helm we sail down the river. These boatmen are renowned for their skill as skippers and fishermen. Most of the small craft including the feluccas that sail on the Nile are commandeered by Nubians. The Nile is a vast river, much wider than I’d expected, and fast flowing.

With our handsome young Nubian boatman at the helm we sail down the river. These boatmen are renowned for their skill as skippers and fishermen. Most of the small craft including the feluccas that sail on the Nile are commandeered by Nubians. The Nile is a vast river, much wider than I’d expected, and fast flowing. Nubia was always a land of mystery and legend. Many of the pharaohs of ancient times were Nubians. At the site of Memphis and Karnak there are Nubian monuments. In 747 BC the city of Thebes, near Karnak, was besieged and the Egyptians called on the Nubian king for protection. Thebes was rescued and for the next 100 years Nubian kings ruled in Egypt. Archaeologists have worked to excavate as many ancient sites as possible and managed to save over 5000 Nubian objects but many of the Nubian treasures still lie beneath the waters of Lake Nasser. One of the archaeological sites that was rescued and restored is Abu Simbal, at the far end of Lake Nasser. Another is the Temple of Philae, restored on a small rocky island once known as Apo, which means “ivory”.

Nubia was always a land of mystery and legend. Many of the pharaohs of ancient times were Nubians. At the site of Memphis and Karnak there are Nubian monuments. In 747 BC the city of Thebes, near Karnak, was besieged and the Egyptians called on the Nubian king for protection. Thebes was rescued and for the next 100 years Nubian kings ruled in Egypt. Archaeologists have worked to excavate as many ancient sites as possible and managed to save over 5000 Nubian objects but many of the Nubian treasures still lie beneath the waters of Lake Nasser. One of the archaeological sites that was rescued and restored is Abu Simbal, at the far end of Lake Nasser. Another is the Temple of Philae, restored on a small rocky island once known as Apo, which means “ivory”. The boat rounds a bend in the river past a mound of giant stones that stand like a sentinel. Not far ahead I see the sand-stone buildings of the Temple of Philae fringed by a stand of palm trees.

The boat rounds a bend in the river past a mound of giant stones that stand like a sentinel. Not far ahead I see the sand-stone buildings of the Temple of Philae fringed by a stand of palm trees.

The temple complex was built during the Ptolemaic dynasty (380-362 BC). Its principal deity was Isis but there are shrines dedicated to other gods. The most ancient temple was one built for Isis, the goddess to whom the first buildings were dedicated. It was approached from the river through a double colonnade. Because it was supposed to be the burial place of Isis’s husband, Osiris, Philae was held in great reverence both by the Egyptians to the north and the Nubians in the south. Only priests could dwell there. On the walls inscriptions tell the story of Osiris and how he was murdered.

The temple complex was built during the Ptolemaic dynasty (380-362 BC). Its principal deity was Isis but there are shrines dedicated to other gods. The most ancient temple was one built for Isis, the goddess to whom the first buildings were dedicated. It was approached from the river through a double colonnade. Because it was supposed to be the burial place of Isis’s husband, Osiris, Philae was held in great reverence both by the Egyptians to the north and the Nubians in the south. Only priests could dwell there. On the walls inscriptions tell the story of Osiris and how he was murdered. The Philae temple was closed in the 6thcentury AD by the Byzantine emperor Justinian. After that it became a seat of the Christian religion. Ruins of a Christian church were discovered on the site. Many of the sculptures and hieroglyphics on the walls of the temple were destroyed or mutilated by these early Christian inhabitants. Most of Horus’s statues were left unmarred but in many of the wall scenes, every figure is scratched out except that of Horus and his winged solar-disk, perhaps because the Byzantine Christians saw some parallel between Horus, the god’s son, and the stories of Jesus.

The Philae temple was closed in the 6thcentury AD by the Byzantine emperor Justinian. After that it became a seat of the Christian religion. Ruins of a Christian church were discovered on the site. Many of the sculptures and hieroglyphics on the walls of the temple were destroyed or mutilated by these early Christian inhabitants. Most of Horus’s statues were left unmarred but in many of the wall scenes, every figure is scratched out except that of Horus and his winged solar-disk, perhaps because the Byzantine Christians saw some parallel between Horus, the god’s son, and the stories of Jesus.

It took two hours to travel the twelve kilometers from downtown Nairobi to Blixen’s farm. The main highway, currently being re-built by the Chinese government, was under heavy construction. Whatever romance I had expected was wiped out by the intense drive. Horns blared. Thick smog reeked of car fumes. Engines idled without any forward movement. Men selling everything from magazines to bananas pressed up against the car. My driver advised me to keep my window closed so I wouldn’t be robbed. With one of the highest crime rates in Africa, Nairobi has the infamous nickname “Now rob me”.

It took two hours to travel the twelve kilometers from downtown Nairobi to Blixen’s farm. The main highway, currently being re-built by the Chinese government, was under heavy construction. Whatever romance I had expected was wiped out by the intense drive. Horns blared. Thick smog reeked of car fumes. Engines idled without any forward movement. Men selling everything from magazines to bananas pressed up against the car. My driver advised me to keep my window closed so I wouldn’t be robbed. With one of the highest crime rates in Africa, Nairobi has the infamous nickname “Now rob me”. Still, as we drove up the laneway, my palms grew damp and I felt anxious, like I was meeting someone I had not seen in several years and was worried about making a good impression. Such is the odd relationship between a reader, a novel and the novelist. The reader feels a tenderness that is one-sided. Loving a novel is always unrequited.

Still, as we drove up the laneway, my palms grew damp and I felt anxious, like I was meeting someone I had not seen in several years and was worried about making a good impression. Such is the odd relationship between a reader, a novel and the novelist. The reader feels a tenderness that is one-sided. Loving a novel is always unrequited. When I opened my door, the spicy smell of Cypress stung my nostrils. Norfolk pines and columnar cypress lined the immaculate grounds. Cultivated shrubs with fushia foliage bordered the front lawn. Delicate blue flowers opened to the cloudless sky. The wide lawn stretched across the front and the back of the house. There was a lot of activity as workers erected great white tents in the backyard for a craft fair on the weekend. The property is popular for weddings and special events.

When I opened my door, the spicy smell of Cypress stung my nostrils. Norfolk pines and columnar cypress lined the immaculate grounds. Cultivated shrubs with fushia foliage bordered the front lawn. Delicate blue flowers opened to the cloudless sky. The wide lawn stretched across the front and the back of the house. There was a lot of activity as workers erected great white tents in the backyard for a craft fair on the weekend. The property is popular for weddings and special events.

I walked into the bedroom. There was a tiny, white bed with a hard looking mattress. A pair of riding boots stood in the centre of the room. Several British tourists shuffled in behind me following their guide. They had paid for a tour and were fans of the 1985 movie, based on the novel, starring Meryl Streep as Karen Blixen and Robert Redford as Denys Finch Hatton, her lover. The guide began his spiel.

I walked into the bedroom. There was a tiny, white bed with a hard looking mattress. A pair of riding boots stood in the centre of the room. Several British tourists shuffled in behind me following their guide. They had paid for a tour and were fans of the 1985 movie, based on the novel, starring Meryl Streep as Karen Blixen and Robert Redford as Denys Finch Hatton, her lover. The guide began his spiel.