Bhutan

by K.D. Leperi

I arrived in the Kingdom of Bhutan, a land-locked country sandwiched in between the giants of India and China, expecting to capture images of a gentle country where Buddhist traditions and conventional culture trump modern materialistic trappings. This is a nation known for its varied terrain: from the subtropical plains and forests in the South to the lofty snow-drenched Himalayan foothills and mountains of the North.

I arrived in the Kingdom of Bhutan, a land-locked country sandwiched in between the giants of India and China, expecting to capture images of a gentle country where Buddhist traditions and conventional culture trump modern materialistic trappings. This is a nation known for its varied terrain: from the subtropical plains and forests in the South to the lofty snow-drenched Himalayan foothills and mountains of the North.

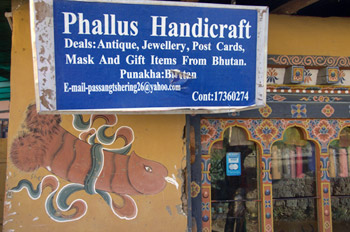

Bhutan is also known for a distinctive culture that celebrates mask dances and requires men and women to wear traditional dress. Most serve a special dish of chili and cheese with almost every meal and they live in unique architectural homes with Bhutanese flourishes such as multi-colored wood frontages, small arched windows, and sloping roofs. No nails or iron bars are allowed in the construction of buildings, and many feature traditional images such as swastikas and phallic paintings.

Phallic symbols are everywhere

I’ll admit to not recognizing the structure of a giant penis on a commercial building at first, thinking it was some elaborate design that I just didn’t get, but a fellow photographer soon pointed it out and identified the ejaculating phallic symbol for me. Initially, I was somewhat taken aback by the penile projectile, but then I began to philosophically contemplate why decorated penises adorned many buildings and homes, and what could it possibly mean. I soon found out from our Bhutanese guide.

I’ll admit to not recognizing the structure of a giant penis on a commercial building at first, thinking it was some elaborate design that I just didn’t get, but a fellow photographer soon pointed it out and identified the ejaculating phallic symbol for me. Initially, I was somewhat taken aback by the penile projectile, but then I began to philosophically contemplate why decorated penises adorned many buildings and homes, and what could it possibly mean. I soon found out from our Bhutanese guide.

The Divine Madman uses penis for enlightenment and fighting evil

Turns out there was a certain individual called Drukpa Kunley, aka the “Divine Madman” a Buddhist master who lived from 1455 -1529 A.D. He is fondly remembered for his most outrageous teachings that were designed to challenge preconceptions. He taught that the ‘divine thunderbolt of wisdom’ comes by way of shock value; an unorthodox combination of drinking, sex rituals, and provocative humor and dance. Because of this, he used his penis quite often to achieve insight and eventually became known as “The Saint of 5,000 Women” due to his penis prowess. In other words, he offered blessings to women in the form of sex. He didn’t discriminate with women as it didn’t matter if she was married or not, virgin or experienced.

Turns out there was a certain individual called Drukpa Kunley, aka the “Divine Madman” a Buddhist master who lived from 1455 -1529 A.D. He is fondly remembered for his most outrageous teachings that were designed to challenge preconceptions. He taught that the ‘divine thunderbolt of wisdom’ comes by way of shock value; an unorthodox combination of drinking, sex rituals, and provocative humor and dance. Because of this, he used his penis quite often to achieve insight and eventually became known as “The Saint of 5,000 Women” due to his penis prowess. In other words, he offered blessings to women in the form of sex. He didn’t discriminate with women as it didn’t matter if she was married or not, virgin or experienced.

Legend also has it that the Divine Madman battled a female demon by beating her in the face with his own genital, which he referred to as ‘The Flaming Thunderbolt of Wisdom,’ and then proceeded to gag her with his extension until she was quashed. Finally, as the story goes, he transformed the defeated spirit into a good spirit through divine sexual play.

This apparently gave rise to painting penises of varying shapes, sizes, and forms on homes and buildings as a protection against deities and bad spirits. Some of the bigger-than-life-size phallic symbols feature brightly colored ribbons tied around them, as if a gift of the gods. Others are graphically depictive, some ejaculating and some complete with pubic hair on the testicles. Some even depict primitive-type eyes. Almost all are featured fully erect.

It is important to note that the ubiquitous phallus paintings and wood carvings are not considered as pornographic or erotic symbols to the Bhutanese, rather they are imbued with protective qualities that ward off evil spirits. After all, the penis proved to be a path for spiritual nourishment and enlightenment for the much revered Divine Madman and his ‘Flaming Thunderbolt of Wisdom’ was used much like a sword to conquer evil spirits as well. A nifty combination.

If You Go:

Private 4-Day Bhutan Tour: Paro, Taktsang Monastery, Thimphu

About the author:

Karin Leperi is an Award Winning Travel Writer/Photographer

Visit Karin’s website

Member, Society of American Travel Writers (SATW)

Member, International Food, Wine & Travel Writers Association (IFWTWA)

Member, World Food Travel Association (WFTA)

Photographs: All photos are by K.D. Leperi.

The next morning we decided to take a walk in Kathmandu. Durbar Square was our first and natural destination. The word Durbar Square may be equivalent to German Marktplatz. Several Nepalese cities have Durbar Squares, which are usually made up of royal and religious buildings. The Kathmandu Durbar Square, which is not free of charge for foreigners to enter, can present a variety of royal courts, temples and monuments (most of them belong to different historical periods), as well as numerous guides and street sellers, who would stalk you all the time and offer their goods and services. Tourists who have some understanding in history and religion, especially that of Indian subcontinent, can be very happy to explore every corner of the square. But even if you do not posses this kind of information, no worries at all. Dozens of guides are always ready to lead you by explaining the history and meaning of each edifice.

The next morning we decided to take a walk in Kathmandu. Durbar Square was our first and natural destination. The word Durbar Square may be equivalent to German Marktplatz. Several Nepalese cities have Durbar Squares, which are usually made up of royal and religious buildings. The Kathmandu Durbar Square, which is not free of charge for foreigners to enter, can present a variety of royal courts, temples and monuments (most of them belong to different historical periods), as well as numerous guides and street sellers, who would stalk you all the time and offer their goods and services. Tourists who have some understanding in history and religion, especially that of Indian subcontinent, can be very happy to explore every corner of the square. But even if you do not posses this kind of information, no worries at all. Dozens of guides are always ready to lead you by explaining the history and meaning of each edifice. Although the Durbar Square contains a lot of historical buildings, it would take too long to explain each of them. But one should certainly visit the Kumari residence. Kumari is a living goddess mainly worshipped by Hindus. In Nepal Kumari is a pre-pubescent girl regularly determined as a result of interesting and complex selection process.

Although the Durbar Square contains a lot of historical buildings, it would take too long to explain each of them. But one should certainly visit the Kumari residence. Kumari is a living goddess mainly worshipped by Hindus. In Nepal Kumari is a pre-pubescent girl regularly determined as a result of interesting and complex selection process. For people, who are eager to see Mt. Everest and some other peaks, I would highly recommend you to take a mountain flight operated by a bunch of domestic airlines in Nepal. As I mentioned above, even small hotels can arrange mountain flights, which can make your job more convenient. You will be taken very high, above the clouds, to the Roof of the World. Kind stewards will show and explain you every of a dozen Himalayan peaks. You can even get a chance to enter to the pilot`s cabin, where an indescribably wonderful and magnificent view will open in front of you. I am sure this mountain flight will be one of the most memorable moments you will recall with a pleasure the rest of your life. But Nepal is not only the Everest. Proud of their history, every Nepalese may tell you their country is the birthplace of Gautama Buddha. The founder of Buddhism was born in 6th century BC in Lumbini, a small town in the southern part of the country. Today Lumbini is a worshipping place, where many Buddhists from all over the world, not only from Nepal come to pay their tribute.

For people, who are eager to see Mt. Everest and some other peaks, I would highly recommend you to take a mountain flight operated by a bunch of domestic airlines in Nepal. As I mentioned above, even small hotels can arrange mountain flights, which can make your job more convenient. You will be taken very high, above the clouds, to the Roof of the World. Kind stewards will show and explain you every of a dozen Himalayan peaks. You can even get a chance to enter to the pilot`s cabin, where an indescribably wonderful and magnificent view will open in front of you. I am sure this mountain flight will be one of the most memorable moments you will recall with a pleasure the rest of your life. But Nepal is not only the Everest. Proud of their history, every Nepalese may tell you their country is the birthplace of Gautama Buddha. The founder of Buddhism was born in 6th century BC in Lumbini, a small town in the southern part of the country. Today Lumbini is a worshipping place, where many Buddhists from all over the world, not only from Nepal come to pay their tribute.

Hanoi is a contrast of old and new with some intriguing contradictions. The National Museum is housed in an old colonial building. The 900 year old Temple of Literature was a center of Confucian learning and thought. The French-era Opera House is beautifully appointed … and located opposite the Hanoi stock exchange in a square that includes a Gucci store and the Hanoi Hilton, that’s the hotel, not the prison which is across town.

Hanoi is a contrast of old and new with some intriguing contradictions. The National Museum is housed in an old colonial building. The 900 year old Temple of Literature was a center of Confucian learning and thought. The French-era Opera House is beautifully appointed … and located opposite the Hanoi stock exchange in a square that includes a Gucci store and the Hanoi Hilton, that’s the hotel, not the prison which is across town. But Hanoi’s Old Quarter is a source of wonder too – vibrant, vigorous, visceral. Delicious pho (pronounced “fa”) dished up in noodle soup restaurants. Egg coffee served on a balcony overlooking Hoan Kiem Lake. Sidewalk food stalls, bakeries, bars and coffeehouses proliferate. The narrow streets are packed with mini hotels and hostels, family shops, crafts and trades, and small businesses – the never-ending hustle of street life.

But Hanoi’s Old Quarter is a source of wonder too – vibrant, vigorous, visceral. Delicious pho (pronounced “fa”) dished up in noodle soup restaurants. Egg coffee served on a balcony overlooking Hoan Kiem Lake. Sidewalk food stalls, bakeries, bars and coffeehouses proliferate. The narrow streets are packed with mini hotels and hostels, family shops, crafts and trades, and small businesses – the never-ending hustle of street life. I’ve been curious about the impact of the “Vietnam War” on this country. Vietnamese history cites many wars, not just the one we talk about. There are earlier wars against the Chinese and the Mongols, conflicts between the Nguyen lords of the north and the Champa kingdom of the south, the war of independence against the French (aka First Indochina War), the civil war (aka Second Indochina War or American War) between north and south divided politically by the 1954 Geneva convention and geographically by the 17th parallel, and most recently the 1980’s war against the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

I’ve been curious about the impact of the “Vietnam War” on this country. Vietnamese history cites many wars, not just the one we talk about. There are earlier wars against the Chinese and the Mongols, conflicts between the Nguyen lords of the north and the Champa kingdom of the south, the war of independence against the French (aka First Indochina War), the civil war (aka Second Indochina War or American War) between north and south divided politically by the 1954 Geneva convention and geographically by the 17th parallel, and most recently the 1980’s war against the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Reminders of the civil war can be found everywhere. In Hanoi, they are present in all the museums. In Hue, capital of the Nguyen Dynasty, a large national flag flies from the Citadel which dominates the Imperial City and Forbidden Purple Palace. The national flag flew here for 28 days when the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army captured the Citadel during the 1968 Tet offensive.

Reminders of the civil war can be found everywhere. In Hanoi, they are present in all the museums. In Hue, capital of the Nguyen Dynasty, a large national flag flies from the Citadel which dominates the Imperial City and Forbidden Purple Palace. The national flag flew here for 28 days when the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army captured the Citadel during the 1968 Tet offensive. Hoi An is a wonderfully historic city, and also a UNESCO World Heritage site. Night lanterns light up the streets of the old town with its Chinese clan houses, pagodas and covered bridges. I stumble upon a house that belonged to one of the early revolutionaries in the city. His grandson proudly shows me photos of grandpa with General Giap, chief architect of the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, and of the strategy that led to the North’s victory in the civil war.

Hoi An is a wonderfully historic city, and also a UNESCO World Heritage site. Night lanterns light up the streets of the old town with its Chinese clan houses, pagodas and covered bridges. I stumble upon a house that belonged to one of the early revolutionaries in the city. His grandson proudly shows me photos of grandpa with General Giap, chief architect of the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, and of the strategy that led to the North’s victory in the civil war. Nha Trang is a sun, sand and sea beach town. It’s predicted to grow exponentially. The Long Son pagoda is full of families praying for good fortune in the new year, and paying their respects to their ancestors. Clouds of incense carry their prayers heavenward past the enormous white Buddha atop the hill overlooking the pagoda. The Tet celebrations culminate in a spectacular fireworks display from barges off the beach. Thousands of people are out to watch, young and old. The beach is vast, and there is much construction in progress. Signs in Russian and English vie for attention.

Nha Trang is a sun, sand and sea beach town. It’s predicted to grow exponentially. The Long Son pagoda is full of families praying for good fortune in the new year, and paying their respects to their ancestors. Clouds of incense carry their prayers heavenward past the enormous white Buddha atop the hill overlooking the pagoda. The Tet celebrations culminate in a spectacular fireworks display from barges off the beach. Thousands of people are out to watch, young and old. The beach is vast, and there is much construction in progress. Signs in Russian and English vie for attention.

I am not too far from the truth – I am at Mirjan fort, near Gokarna. The fort, built first in the 12th century and extended in the 16th century, has a long and glorious history. It was the seat of Rani Chennabhairadevi, ruling under the aegis of the Vijayanagar Empire. She was better known as the Pepper Queen, or Raina da Pimenta, as she controlled the spice trade in the area. The fort was especially conducive for trade, located as it was, on the banks of the Aghanashini River, a branch of the Sharavati. The fort changed hands many times, from the Rani to the Sultans of Bijapur, the Marathas, and eventually the British. The unification of the area under the British, as well as the setting up of newer and modern ports along the coast, ultimately rendered the fort ineffectual, and it was abandoned, leaving nature to reclaim it for her own.

I am not too far from the truth – I am at Mirjan fort, near Gokarna. The fort, built first in the 12th century and extended in the 16th century, has a long and glorious history. It was the seat of Rani Chennabhairadevi, ruling under the aegis of the Vijayanagar Empire. She was better known as the Pepper Queen, or Raina da Pimenta, as she controlled the spice trade in the area. The fort was especially conducive for trade, located as it was, on the banks of the Aghanashini River, a branch of the Sharavati. The fort changed hands many times, from the Rani to the Sultans of Bijapur, the Marathas, and eventually the British. The unification of the area under the British, as well as the setting up of newer and modern ports along the coast, ultimately rendered the fort ineffectual, and it was abandoned, leaving nature to reclaim it for her own. From the outside, it is still apparent why the fort was such a stronghold. Spread over an area of 10 acres, huge double walls protect the interiors, and the whole fort is surrounded by a moat, which, in its heyday, was connected to the river, fed by canals which continue to irrigate the fertile fields which surround the area.

From the outside, it is still apparent why the fort was such a stronghold. Spread over an area of 10 acres, huge double walls protect the interiors, and the whole fort is surrounded by a moat, which, in its heyday, was connected to the river, fed by canals which continue to irrigate the fertile fields which surround the area. What we can see of the fort is simply the tip of the iceberg. Literally, it’s only the top portion of the fort which is accessible today. More interesting are the underground chambers and passages, built for protection and to facilitate escape, but which today lie in ruins, and are unapproachable. The ASI is, to give them credit, trying to restore the fort to its former glory. The fort was built using the locally available laterite stones, and we saw ASI personnel at work, trying to restore the turrets with remnants from the ruins or similar laterite stones, still plentiful in the area.

What we can see of the fort is simply the tip of the iceberg. Literally, it’s only the top portion of the fort which is accessible today. More interesting are the underground chambers and passages, built for protection and to facilitate escape, but which today lie in ruins, and are unapproachable. The ASI is, to give them credit, trying to restore the fort to its former glory. The fort was built using the locally available laterite stones, and we saw ASI personnel at work, trying to restore the turrets with remnants from the ruins or similar laterite stones, still plentiful in the area.

Basilica De Bom Jesus with its imposing facade and baroque architecture stands tall and was the first one that I visited. The Basilica looked quite different from others with respect to its dark colour and size. Though it might seem dilapidated at the first look, the Basilica with its reddish brown colour, ornamented pillars and magnificent carvings stands rock solid even after 400 years. Dedicated to infant Jesus, this grand structure also rests the mortal remains of St.Francis Xavier which is taken out for public viewing once in ten years. The interiors of the basilica has a lot of art work, murals and numerous altars which captivate every visitor.

Basilica De Bom Jesus with its imposing facade and baroque architecture stands tall and was the first one that I visited. The Basilica looked quite different from others with respect to its dark colour and size. Though it might seem dilapidated at the first look, the Basilica with its reddish brown colour, ornamented pillars and magnificent carvings stands rock solid even after 400 years. Dedicated to infant Jesus, this grand structure also rests the mortal remains of St.Francis Xavier which is taken out for public viewing once in ten years. The interiors of the basilica has a lot of art work, murals and numerous altars which captivate every visitor. Half a kilometer away lies the beautiful Viceroy’s Arch next to Mandovi quay. The arch built in 16th century must have been witness to thousands of people landing on the Goan shores. Near to the arch lies the Gateway of the palace of Adil Shah. Built before the arrival of the Portuguese, it is only the gateway that survives now.

Half a kilometer away lies the beautiful Viceroy’s Arch next to Mandovi quay. The arch built in 16th century must have been witness to thousands of people landing on the Goan shores. Near to the arch lies the Gateway of the palace of Adil Shah. Built before the arrival of the Portuguese, it is only the gateway that survives now.

Next to the Augustine tower lies the Convent of Santa Monica and a christian museum which definitely is worth a visit.

Next to the Augustine tower lies the Convent of Santa Monica and a christian museum which definitely is worth a visit.