People’s Republic of China

by Mikko Hizon

Macau is a unique story among the world’s most popular tourist destinations, as it’s one of the few to pull off a successful — if you measure success by wealth and money — transition from a quiet sleepy port town into the top gambling destination in the world, eclipsing even the bright lights of Las Vegas. Millions of gamblers flock to Macau to play casino games such as slots, baccarat, and roulette yet the former Portuguese colony retains much of its unique character and charm, with nearly five centuries of history behind it. Visitors who are solely interested in gambling can revel in many of the world’s largest casino, with cavernous halls dedicated to nothing more than chasing Lady Luck, while those with an eye for history can find plenty to enjoy as well.

If you’re looking for cheap and at the same time world class accommodation, check out the Grandview Hotel Macau and Metropark Hotel where rates start rock bottom at only $75 per night! They have all the amenities and the rooms are cozy and crisp that even the luxury seekers can like. Free jacuzzi, sauna and gym use isn’t a bad addition for both hotels as well! Another thing a jet setter would never forget is to taste the local dishes and savor the flavors being offered by the destination. In Macau, do not forget to dine at Wong Chi Kei as they offer the most famous traditional Cantonese noodle dishes with outlets at Rua de Cinco de Outubro and another one near Senado Square. Noodles usually cost $2-3 only and you’ll be surprised that what you get is way more than what you pay for because most dishes are good for 2 people. You’d also enjoy the dessert stalls located in Senado Square. Don’t forget to drop by Lai Kei Ice Cream for homemade ice cream goodness.

Ancient temples, churches, statues, and plazas dot the port, including top destinations such as the Plaza Senado, St. Francis Xavier Chapel, the ruins of St. Paul’s, the A-Ma Temple, and the Guia fortress. One of the unique charms of Macau is the mixture and mingling of Portugese and Chinese elements, which is present not only in the architecture but also in the traditional foods you’ll find. Macau was a key point for the spread of Christianity into both China and Japan, so you’ll also find traditional Christian churches and other influences throughout Macau. Museums and art galleries are also popular, including the Museum of Macau and the Museum of Art.

Ancient temples, churches, statues, and plazas dot the port, including top destinations such as the Plaza Senado, St. Francis Xavier Chapel, the ruins of St. Paul’s, the A-Ma Temple, and the Guia fortress. One of the unique charms of Macau is the mixture and mingling of Portugese and Chinese elements, which is present not only in the architecture but also in the traditional foods you’ll find. Macau was a key point for the spread of Christianity into both China and Japan, so you’ll also find traditional Christian churches and other influences throughout Macau. Museums and art galleries are also popular, including the Museum of Macau and the Museum of Art.

If you’d like to get away from the hustle and bustle of the city and main tourist areas, the villages of Taipa and Coloane offer a look into just what life was like in the past, with the daily life and routine of many villagers unchanged over the last several centuries. Nearby islands also host very popular beaches such as Hac Sa beach, where you can enjoy the famous black sand beach as well as restaurants such as Fernando’s, which is famed for its Portuguese menu and comfortable, laid-back atmosphere. After being a thriving bustling port in the 15th and 16th centuries Macau slowly slipped into obscurity, an important fact to remember when visiting. Macau has become synonymous with the chance to play casino games in various new mega casinos but step outside the busier areas and you’ll encounter a much different Macau, one very similar to what you’d find if you’d visited during the 18th or 19th centuries.

For the adventure seekers in the audience, Macau offers a wealth of opportunities for swimming, karting, windsurfing, canoeing, diving, and horse-back riding, as well as the chance to attend (or even participate in) sporting events such as the Macau Open golf tournament, the Macau Grand Prix, and the Macau International Marathon. Guided tours are available for many of the outdoor activities in Macau, but it’s also possible to go it alone and plan out your own adventures, as numerous rental shops are available and provide everything you’ll need.

If You Go:

AIR

Try checking Air Asia for the lowest fares available. Some start at only $10!

SEA

Catch the ferry from Hong Kong to enjoy the views and really savor the experience! The ferry costs around $12-100 depending on the type of cabin you take. Be sure to bring a jacket or even a windbreaker as these waters are surprisingly cold.

CHEAP HOTELS

Check out the Grandview Hotel Macau and Metropark Hotel where rates start rock bottom at only $75 per night. They have all the amenities and the rooms are cozy and crisp that even the luxury seekers can like.

About the author:

Mikko Hizon is a film buff and an avid blogger with a penchant for traveling. Catch him in sporting events as well as he is very fond of basketball especially the Los Angeles Lakers! Visit www.solereapers.com to view his personal blog.

Photo Credits:

Macau Venetian canal by: WiNG / CC BY-SA

Macau skyline by: kewl.lu / CC BY

Hac Sa Beach by: English: Abasaa日本語: あばさー / Public domain

My first stop is the hypocenter upon which sixty-six years ago, the world’s first atomic bomb was used against human targets. Aimed at the T-shaped Aioi Bridge near the geographic center of town, wind blew the bomb slightly off course some 500 meters to the southwest where it detonated over Shima Hospital.

My first stop is the hypocenter upon which sixty-six years ago, the world’s first atomic bomb was used against human targets. Aimed at the T-shaped Aioi Bridge near the geographic center of town, wind blew the bomb slightly off course some 500 meters to the southwest where it detonated over Shima Hospital.

I have a special Japanese friend serving as my informal guide on this trip. Her name is Koko, and she is a remarkable woman. She was just eight months old when Hiroshima was destroyed, so has no direct memory of that day. Yet the bomb has shaped and defined her life in many inscrutable ways. Standing not much more than four feet tall with salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a bun, she looks mild, but in relating the story of her journey from infant in the wrong place at the wrong time – the epitome of an innocent bystander – to peace activist and nuclear critic, she speaks with a stirring fervency, translating her Japanese into her own fluent, vivid English.

I have a special Japanese friend serving as my informal guide on this trip. Her name is Koko, and she is a remarkable woman. She was just eight months old when Hiroshima was destroyed, so has no direct memory of that day. Yet the bomb has shaped and defined her life in many inscrutable ways. Standing not much more than four feet tall with salt-and-pepper hair pulled into a bun, she looks mild, but in relating the story of her journey from infant in the wrong place at the wrong time – the epitome of an innocent bystander – to peace activist and nuclear critic, she speaks with a stirring fervency, translating her Japanese into her own fluent, vivid English. This is the pep block. There is almost no canned music at a Japanese baseball game. Instead, a bare-bones band leads the rabid fans whenever the Carp are up to bat. Bleating trumpets and pounding drums, elaborate sing-song chants with prescribed movements. The crowd cheers, “Bonzai!” then lapses into a pointed silence when the Tokyo Giants are up to bat. They reel their energy in again, least it accidentally offer encouragement to the other team. This is unrivaled in American sports anywhere; American sporting fans would be ashamed.

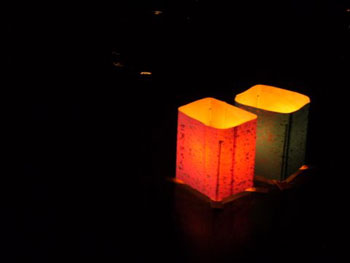

This is the pep block. There is almost no canned music at a Japanese baseball game. Instead, a bare-bones band leads the rabid fans whenever the Carp are up to bat. Bleating trumpets and pounding drums, elaborate sing-song chants with prescribed movements. The crowd cheers, “Bonzai!” then lapses into a pointed silence when the Tokyo Giants are up to bat. They reel their energy in again, least it accidentally offer encouragement to the other team. This is unrivaled in American sports anywhere; American sporting fans would be ashamed. There is a spiritual sense of communion, a union of the intimate and the universal found at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park this evening. The park is the site of the toro nagashi, or lantern ceremony, a traditional Japanese memorial service for the dead. It is by far the most moving part of the day. The skeletal A-Bomb Dome glows bright in the dark, its reflection dancing and shifting shape on the dark surface of the river like some Rorschach test of tragedy, an all-purpose steel and stone reminder of the fragility of even the most durable of man’s accomplishments.

There is a spiritual sense of communion, a union of the intimate and the universal found at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park this evening. The park is the site of the toro nagashi, or lantern ceremony, a traditional Japanese memorial service for the dead. It is by far the most moving part of the day. The skeletal A-Bomb Dome glows bright in the dark, its reflection dancing and shifting shape on the dark surface of the river like some Rorschach test of tragedy, an all-purpose steel and stone reminder of the fragility of even the most durable of man’s accomplishments.

With a population of fifteen million, Dhaka is not the easiest place to get around. It takes about an hour and a half to drive five miles, and it’s not safe to walk or cycle. So you eventually give up trying.

With a population of fifteen million, Dhaka is not the easiest place to get around. It takes about an hour and a half to drive five miles, and it’s not safe to walk or cycle. So you eventually give up trying.

Our two-hour journey was not wasted: Mithu, speaking excellent English, gave us his views on Bangladeshi politics, current issues, transport, and so on. Our first stop was Curzon Hall, named after Lord Curzon, the former British Viceroy to India. It was built in 1904 as a Town Hall, and is now part of Dhaka University’s science faculty. It is a harmonious blend of Mughal and European architecture, built in red brick. Set a little back from the busy main road, near a small lake, it has a peaceful feel about it. Curzon Hall is historically significant. In 1948, after the partition that established what is now Bangladesh as East Pakistan, this was the seat of the language movement, which opposed the imposition of Urdu as the sole national language of Pakistan.

Our two-hour journey was not wasted: Mithu, speaking excellent English, gave us his views on Bangladeshi politics, current issues, transport, and so on. Our first stop was Curzon Hall, named after Lord Curzon, the former British Viceroy to India. It was built in 1904 as a Town Hall, and is now part of Dhaka University’s science faculty. It is a harmonious blend of Mughal and European architecture, built in red brick. Set a little back from the busy main road, near a small lake, it has a peaceful feel about it. Curzon Hall is historically significant. In 1948, after the partition that established what is now Bangladesh as East Pakistan, this was the seat of the language movement, which opposed the imposition of Urdu as the sole national language of Pakistan. We were in luck. Several shops sold them, and after some good-humoured bargaining, we had bought nine. From Virginia’s e-mails, I understood she fancied animals, which we found, and aeroplanes, which we didn’t though there were pictures of several other scenes depicting forms of transport which we bought. (Example below)

We were in luck. Several shops sold them, and after some good-humoured bargaining, we had bought nine. From Virginia’s e-mails, I understood she fancied animals, which we found, and aeroplanes, which we didn’t though there were pictures of several other scenes depicting forms of transport which we bought. (Example below) The street was lined with tightly packed with tailors, hairdressers, and hawkers. Women filled up their pitchers at standpipes, and carts laden with pineapples wove their way through the general chaos.

The street was lined with tightly packed with tailors, hairdressers, and hawkers. Women filled up their pitchers at standpipes, and carts laden with pineapples wove their way through the general chaos. Our last stop was the Sadarghat, Dhaka’s boat terminal. It is from here that you can head south towards the Bay of Bengal – or simply cross the river.

Our last stop was the Sadarghat, Dhaka’s boat terminal. It is from here that you can head south towards the Bay of Bengal – or simply cross the river.

I started my search in Jinli Ancient Street, one of the few remaining spots where the vestiges of a rapidly disappearing culture are permitted to shine through, albeit under the strict control of the local tourist board. I walked along the cobbled streets determined to ignore the overhead neon lighting and pumping music.

I started my search in Jinli Ancient Street, one of the few remaining spots where the vestiges of a rapidly disappearing culture are permitted to shine through, albeit under the strict control of the local tourist board. I walked along the cobbled streets determined to ignore the overhead neon lighting and pumping music.

It was when I was hanging around one of the quieter stalls that I truly felt like I had found a moment to enjoy the China that was spread over the glossy pages of the travel magazines. Beneath bobbing red lanterns and the dangling sea of wishes entwined within the branches of a clematis, a crowd gathered to watch the shadow play of the Hidden People.

It was when I was hanging around one of the quieter stalls that I truly felt like I had found a moment to enjoy the China that was spread over the glossy pages of the travel magazines. Beneath bobbing red lanterns and the dangling sea of wishes entwined within the branches of a clematis, a crowd gathered to watch the shadow play of the Hidden People. The following day I decided to head to Chengdu’s must-see panda sanctuary. I eagerly welcomed the green haven after the polluted streets, yet it was still impossible to escape China’s infamous crowds. Through the throngs of tourists and clapping children, I eased my way to the front in time to see an incredibly docile panda obligingly pose for pictures next to newly-weds. They had tentatively entered the enclosure and now grinned into the flashing cameras.

The following day I decided to head to Chengdu’s must-see panda sanctuary. I eagerly welcomed the green haven after the polluted streets, yet it was still impossible to escape China’s infamous crowds. Through the throngs of tourists and clapping children, I eased my way to the front in time to see an incredibly docile panda obligingly pose for pictures next to newly-weds. They had tentatively entered the enclosure and now grinned into the flashing cameras. Having had my fill of panda enclosures, I wandered down to the lake for green tea and noodles. It seemed even the massing fish had learnt to manipulate the tourists, and as I watched them writhing to the surface to chow down upon the tossed breadcrumbs, I wondered what this place would be like without the protection of the sanctuary. It seemed to me the only animals in the park that were not somehow manipulated by the crowds were the unusual black swans that glided across the surface of the lake. Necks outstretched and wings beating in harmony with their mates, they seemed oblivious to the snap happy tourists.

Having had my fill of panda enclosures, I wandered down to the lake for green tea and noodles. It seemed even the massing fish had learnt to manipulate the tourists, and as I watched them writhing to the surface to chow down upon the tossed breadcrumbs, I wondered what this place would be like without the protection of the sanctuary. It seemed to me the only animals in the park that were not somehow manipulated by the crowds were the unusual black swans that glided across the surface of the lake. Necks outstretched and wings beating in harmony with their mates, they seemed oblivious to the snap happy tourists.

Pale and blond, I stand out everywhere I go in China, but never more so than at this precise moment, I realize. Literally, every other person in this line – all several thousand of them – is Chinese. I feel not just self-conscious, but downright uncomfortable. People are looking at me. Staring at me. Chinese have no compunctions about this, it seems. They’re eyeing me openly. I’m sweating, and the sun is barely even up yet.

Pale and blond, I stand out everywhere I go in China, but never more so than at this precise moment, I realize. Literally, every other person in this line – all several thousand of them – is Chinese. I feel not just self-conscious, but downright uncomfortable. People are looking at me. Staring at me. Chinese have no compunctions about this, it seems. They’re eyeing me openly. I’m sweating, and the sun is barely even up yet.

“Ah, yes!” He is pleased with this answer, and he decides in this moment that I am alright. He is going to be my new best friend until we get through this line. He turns to the crowd which is still staring shamelessly at me and offers a translation of our exchange. Smiles and waves all around. And I rejoice, not only because I am no longer quite so isolated in this sea of humanity, but because seeing Mao is only half of the experience – it’s not complete without the interactive and earnest reactions from a real Chinese. I wanted to learn, and I am going to.

“Ah, yes!” He is pleased with this answer, and he decides in this moment that I am alright. He is going to be my new best friend until we get through this line. He turns to the crowd which is still staring shamelessly at me and offers a translation of our exchange. Smiles and waves all around. And I rejoice, not only because I am no longer quite so isolated in this sea of humanity, but because seeing Mao is only half of the experience – it’s not complete without the interactive and earnest reactions from a real Chinese. I wanted to learn, and I am going to. We draw near the door, through several layers of security, and Dalian wants to buy a yellow carnation to leave as an offering to Mao. But he misses the flower stand in the heat of our conversation, and the soldiers won’t let him go back for one. Despite his pleading. Here’s where he comes closest to tears. But the line toward the inner chamber of Mao’s Mausoleum is ever-moving and inexorable. Even though he says he has been here so many times that he can’t count them, this ritual clearly means a lot to him. It is secular religion here, and I have brought a modicum of shame upon him before his Lord. He tells me that having the chance to guide an American through this experience is honor enough.

We draw near the door, through several layers of security, and Dalian wants to buy a yellow carnation to leave as an offering to Mao. But he misses the flower stand in the heat of our conversation, and the soldiers won’t let him go back for one. Despite his pleading. Here’s where he comes closest to tears. But the line toward the inner chamber of Mao’s Mausoleum is ever-moving and inexorable. Even though he says he has been here so many times that he can’t count them, this ritual clearly means a lot to him. It is secular religion here, and I have brought a modicum of shame upon him before his Lord. He tells me that having the chance to guide an American through this experience is honor enough.