Czech Republic

by Emily Monaco

What do rock and roll music and the fall of the Iron Curtain have in common? In Prague, the answer is quite a bit.

I’ve always been fascinated by revolutions and rebellions, particularly in countries that I’m otherwise not that familiar with. There’s little more evocative of what makes a people tick than what makes them revolt… and the Velvet Revolution in Prague is no different. Which is why when I visited Prague for the first time, I set out to learn all I could about this revolution, seeking clues to this history in modern Prague.

Prague fell to a Communist Coup d’état in February 1948, known in Communist historiography as “Victorious February.” This set the stage for many years of cultural and historical development – development that, oddly enough, is frequently linked to a rock star who was living on the other side of the Atlantic at the time.

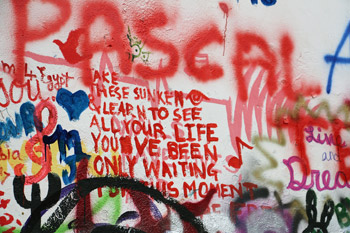

Many come to Prague to visit the John Lennon Wall, a wall technically belonging to the Knights of Malta that’s completely covered in graffiti devoted to Lennon. But how many people know what this emblem to one of Western music’s most important figures means to locals of Prague? I decided to find out.

A Museum and Mausoleum for Czech Communism

In order to understand Prague’s revolution, one must understand what led to it, and there’s nothing better than the Communism museum for this. The museum is full of exhibits of life under the regime, though one gets the feeling that it’s rather tongue in cheek, given the postcards devoted to life under Communism – “You couldn’t get laundry detergent, but you could get your brainwashed”; “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.” That was my first clue that music had something to do with all of this dark history.

In order to understand Prague’s revolution, one must understand what led to it, and there’s nothing better than the Communism museum for this. The museum is full of exhibits of life under the regime, though one gets the feeling that it’s rather tongue in cheek, given the postcards devoted to life under Communism – “You couldn’t get laundry detergent, but you could get your brainwashed”; “It was a time of happy, shiny people. The shiniest were in the uranium mines.” That was my first clue that music had something to do with all of this dark history.

A fairly no-nonsense timeline is nevertheless available at the beginning of the museum, detailing how Prague eventually ended up under a Communist régime for several decades. But what’s more interesting, at least to me, are the exhibits that show what life was really like – school, daily life, shopping… — under Communism.

The exhibit ends with a video, images that we don’t have of other European revolutions that took place too long ago. Images of people marching along Wenceslas Square, calling out for freedom, for the end of Communism and the beginning of something new. And behind it all, a soundtrack for the ages. This was only the beginning of my discovery, but everything I encountered would point back to this video, this peaceful protest.

How Music Saved Their Souls

The Prague Spring came about in 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubcek was elected as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Reforms by Dubcek were intended to grant more rights to citizens, including loosening strict restrictions on media – for the first time, young Czechs could listen to the Beatles on the radio. That was one thing that surprised me as I wandered the Communist museum – how willing locals were to seek out their favorite rock groups from America, buying records on vinyl from Western Europe and listening to them in secret.

The Prague Spring came about in 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubcek was elected as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Reforms by Dubcek were intended to grant more rights to citizens, including loosening strict restrictions on media – for the first time, young Czechs could listen to the Beatles on the radio. That was one thing that surprised me as I wandered the Communist museum – how willing locals were to seek out their favorite rock groups from America, buying records on vinyl from Western Europe and listening to them in secret.

Unsurprisingly, the Soviets did not take Dubcek’s attempts in favor of change well. The country was occupied after failed negotiations, and non-violent resistance began throughout the country, lasting 8 months. Bear these non-violent resistances in mind – they’ll come back later.

1968 was an important year for other reasons linked not to politics but to music. Of course, in this case, it’s hard to separate the two. While some young Czechs were listening to the newly released “Revolution” B-Side of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude” single, others were listening to more works of rock and roll.

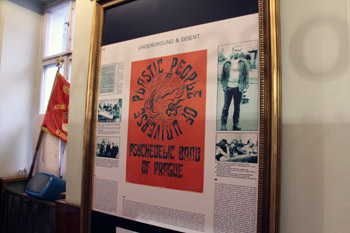

Inspired by the Velvet Underground, a group of Prague natives formed a band called the Plastic People of the Universe, just a month after the Prague Spring was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops and just after Jan Palach, a philosophy student, set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square, issuing a warning before his death not to follow in his footsteps, a warning displayed on the walls of the Communism museum. The Plastic People played psychedelic garage rock typical of American FM stations of the time – led by front man Milan Hlavsa, a butcher by training, the group sang controversial songs of freedom, first in English, then in Czech. Their first studio album was called “Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,” an ironic spin on poems by outlawed Czech poet Egon Bondy and the everpresent Liverpudlian Fab Four.

Inspired by the Velvet Underground, a group of Prague natives formed a band called the Plastic People of the Universe, just a month after the Prague Spring was suppressed by Warsaw Pact troops and just after Jan Palach, a philosophy student, set himself on fire on Wenceslas Square, issuing a warning before his death not to follow in his footsteps, a warning displayed on the walls of the Communism museum. The Plastic People played psychedelic garage rock typical of American FM stations of the time – led by front man Milan Hlavsa, a butcher by training, the group sang controversial songs of freedom, first in English, then in Czech. Their first studio album was called “Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned,” an ironic spin on poems by outlawed Czech poet Egon Bondy and the everpresent Liverpudlian Fab Four.

Nearly everything the Plastic People did was illegal in Prague at the time. It was hard to know what would be outlawed next – laughing in a cinema, singing English songs. Professional musicians were required to wear their hair short, but the Plastics wore their hair long. Their dark, subversive lyrics got them thrown in jail for years. And yet they kept playing… and people kept listening.

In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing them to take the second part of the band title that had so inspired them literally – the Plastics were going underground. For years, they remained relatively off the radar, until 1976, when they played a music festival in the town of Bojanvovice, leading to arrests of all of the band members on charges of “subversive activities against the state.”

In 1970, the Communist government revoked the license for the Plastics to perform in public, forcing them to take the second part of the band title that had so inspired them literally – the Plastics were going underground. For years, they remained relatively off the radar, until 1976, when they played a music festival in the town of Bojanvovice, leading to arrests of all of the band members on charges of “subversive activities against the state.”

But nearly 10 years later, their message still pulsed throughout Prague. In 1989, Velvet was no longer Underground – evolving slowly from the moment that people like the Plastics first began to question authority, the Velvet Revolution had arrived in the city.

The Velvet Revolution – Resistance in Song

Marta Kubisova is just one of the many Czechs who was inspired by the “Hey Jude” single. The actress and singer first graced the public eye when “Prayer for Marta” became a symbol of national resistance in 1968, during the Prague Spring. And in the same year, when “Hey Jude” was released, Marta adapted it, releasing her own translated version in 1969 – the cover made her a local star.

Marta Kubisova is just one of the many Czechs who was inspired by the “Hey Jude” single. The actress and singer first graced the public eye when “Prayer for Marta” became a symbol of national resistance in 1968, during the Prague Spring. And in the same year, when “Hey Jude” was released, Marta adapted it, releasing her own translated version in 1969 – the cover made her a local star.

After a falsified pornography lawsuit, she was unable to work in many different places and ended up auditioning for the Plastic People of the Universe, a move disallowed by the secret police. On November 22nd, after several days of peaceful student protests and 20 years of having been banned from appearing in public, Marta sang “Prayer for Marta” from a balcony on Wenceslas Square.

Let peace continue with this country.

Let wrath, envy, hate, fear and struggle vanish.

Now, when the lost reign over your affairs will return to you, people, it will return.”

– “Prayer for Marta”

The biggest difference between the Velvet Revolution and any other revolution I’ve studied is the modifier: velvet. Stemming perhaps from a belief forged by the Plastics — that any dialogue with the totalitarian regime was futile and it was better to simply turn one’s back — the Velvet Revolutionaries did not fight for freedom, per se, but merely acted as though they were already free. The students walked. Marta sang. And it worked.

Revolution and Rock and Roll in Prague Today

Today, the John Lennon wall still attracts hundreds of tourists, who come to look at the ever-changing paintings. The Knights of Malta have long since ceased trying to stop the graffiti. But while John Lennon is a meaningful symbol for many, it’s hard to understand just how much his music meant to young Czechs in the 80s.

Today, the John Lennon wall still attracts hundreds of tourists, who come to look at the ever-changing paintings. The Knights of Malta have long since ceased trying to stop the graffiti. But while John Lennon is a meaningful symbol for many, it’s hard to understand just how much his music meant to young Czechs in the 80s.

The wall first popped up in 1980, just after Lennon’s death, just a few years before Prague students took to the streets. The wall was created in memory of the man who, for them, embodied the freedom and liberation they so craved. “Lennonism,” then, a celebration of freedom and independence, became the counterpoint to Communism, and the evidence remains in Prague today, years after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

The wall first popped up in 1980, just after Lennon’s death, just a few years before Prague students took to the streets. The wall was created in memory of the man who, for them, embodied the freedom and liberation they so craved. “Lennonism,” then, a celebration of freedom and independence, became the counterpoint to Communism, and the evidence remains in Prague today, years after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

As I walk through modern Prague, I see music everywhere – folk metal bagpipe players on a central square, a lone guitarist in a fringed suede jacket playing a Beatles song. I find Wenceslas Square, finally, on one of my last days in Prague. It’s understated and small, hardly even labeled – it seems, to me, to be the perfect place for Velvet.

Skip-the-Line Museum of Communism Ticket and Prague City Private Tour

If You Go:

♦ Museum of Communism – Na príkope 852/10, 110 00 Praha 1

♦ National Museum – U Památníku 1900, 130 00 Praha 3 (The Music and Politics exhibit runs the end of March 2015)

♦ The Museum and Archive of Popular Music – Belohorská 201/150, 169 00 Praha

About the author:

Emily Monaco is a native New Yorker living in Paris. She earned a Master’s degree in 19th century French literature from the Sorbonne and now writes about revolution, cheese, and beer. Discover her experiences with Franglais and food on her blog, tomatokumato.com. Her writing has been featured in That’s Paris, an anthology about life in Paris.

All photos by Emily Monaco:

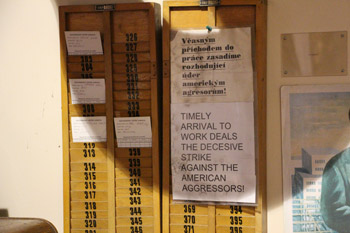

Communist anti-American propaganda at the Prague Communism Museum.

School under Communism as depicted at the Prague Communism Museum.

A hidden record player displayed at the Prague Communism Museum.

A Plastic People of the Universe poster.

The lyrics to “Blackbird” painted on the John Lennon Wall.

Paintings of John Lennon on the John Lennon Wall.

A folk metal bagpipe player busking in Prague.

A lone dog crossing an empty Wenceslas Square.

When, just over a week ago, I arrived in Valencia, Spain’s third largest city located on the Mediterranean and full of history, I did so, literally, with a bang. It’s the time of year when a spectacular festival, known as Las Falles, is celebrated, culminating on the 19th of March with a parade of gigantic ninots, papier-mâché effigies which are, at the end, burnt in a massive bonfire to chase winter out and welcome spring. Fireworks, crackers, you name it, anything which makes noise and has color will assault the senses.

When, just over a week ago, I arrived in Valencia, Spain’s third largest city located on the Mediterranean and full of history, I did so, literally, with a bang. It’s the time of year when a spectacular festival, known as Las Falles, is celebrated, culminating on the 19th of March with a parade of gigantic ninots, papier-mâché effigies which are, at the end, burnt in a massive bonfire to chase winter out and welcome spring. Fireworks, crackers, you name it, anything which makes noise and has color will assault the senses. The story of the Holy Grail or chalice, which is the cup Jesus supposedly used during the Last Supper, has fired the imagination over centuries. Did it survive, where was it, is the story really true?

The story of the Holy Grail or chalice, which is the cup Jesus supposedly used during the Last Supper, has fired the imagination over centuries. Did it survive, where was it, is the story really true? Given the many legends, it is not surprising that there are more than one chalice which lay claim to being the ‘real thing’. It will appear though that the chalice kept in the cathedral of Valencia has the most valid claim to authenticity. At least, it has been the official papal chalice for centuries, last used as such by Pope Benedict XVI in June 2006. It was given to the cathedral of Valencia by King Alfonso V of Aragon in 1436.

Given the many legends, it is not surprising that there are more than one chalice which lay claim to being the ‘real thing’. It will appear though that the chalice kept in the cathedral of Valencia has the most valid claim to authenticity. At least, it has been the official papal chalice for centuries, last used as such by Pope Benedict XVI in June 2006. It was given to the cathedral of Valencia by King Alfonso V of Aragon in 1436. It’s very easy to get around Valencia’s historic center on foot, leading past several other landmarks like the Central Market and La Lonja de la Seda, the silk exchange. The cathedral was consecrated in 1238 and is basically a Gothic structure. Built over a former Visgothic cathedral which was turned into a mosque during the occupation by the Arabs, the cathedral also shows Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque and Neo Classical elements. What first catches the eye is Miguelete, the octagonal bell tower which looms up near the main portal and can be climbed, offering a fabulous view over the city, port and river.

It’s very easy to get around Valencia’s historic center on foot, leading past several other landmarks like the Central Market and La Lonja de la Seda, the silk exchange. The cathedral was consecrated in 1238 and is basically a Gothic structure. Built over a former Visgothic cathedral which was turned into a mosque during the occupation by the Arabs, the cathedral also shows Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque and Neo Classical elements. What first catches the eye is Miguelete, the octagonal bell tower which looms up near the main portal and can be climbed, offering a fabulous view over the city, port and river.

Created for mules and packhorses, the narrow streets are steep and best experienced on foot. We park the car and explore this village of Moorish roots dating back to 1448. A map painted on a whitewashed wall provides a guide around the historic section. We wander the almost perpendicular avenues, passing quaint tiled courtyards decorated with flowers and greenery in terracotta pots. The pristine white houses accented with charming old wooden doors are postcard worthy. We soon reach Juana de Escalante Passage, the remainder of the centre of the old Muslim town, tucked in a side street.

Created for mules and packhorses, the narrow streets are steep and best experienced on foot. We park the car and explore this village of Moorish roots dating back to 1448. A map painted on a whitewashed wall provides a guide around the historic section. We wander the almost perpendicular avenues, passing quaint tiled courtyards decorated with flowers and greenery in terracotta pots. The pristine white houses accented with charming old wooden doors are postcard worthy. We soon reach Juana de Escalante Passage, the remainder of the centre of the old Muslim town, tucked in a side street. This was the site of a Moorish rebellion in 1568. The niece of the cleric, Juana de Escalante, stopped the rebels by throwing stones at them from the tower until aid came from Marbella. All that remains is the site the tower once stood on, the round archway and the courtyard through which horses passed through on the way to the stables. Standing there I sense the walls could tell many stories over the centuries. I look down and observe the detailed tile work on the ground. It is a work of art.

This was the site of a Moorish rebellion in 1568. The niece of the cleric, Juana de Escalante, stopped the rebels by throwing stones at them from the tower until aid came from Marbella. All that remains is the site the tower once stood on, the round archway and the courtyard through which horses passed through on the way to the stables. Standing there I sense the walls could tell many stories over the centuries. I look down and observe the detailed tile work on the ground. It is a work of art. Throughout the village is a series of water fountains providing fresh water for the inhabitants over the centuries. The fountains are as attractive as functional; decorated with blue and white tiles, some painted with scenes of the area. The mountain water is prized for its purity.

Throughout the village is a series of water fountains providing fresh water for the inhabitants over the centuries. The fountains are as attractive as functional; decorated with blue and white tiles, some painted with scenes of the area. The mountain water is prized for its purity.

The ruin of Montségur perches on a hilltop in the foothills of the Pyrenees. My arduous climb to this lonely crag is rewarded with panoramic views of lush hillsides dotted with purple blooming wild sage and silent sheep. All that remains of the castle are crumbling walls and part of a keep. A sighing wind whispers over the walls.

The ruin of Montségur perches on a hilltop in the foothills of the Pyrenees. My arduous climb to this lonely crag is rewarded with panoramic views of lush hillsides dotted with purple blooming wild sage and silent sheep. All that remains of the castle are crumbling walls and part of a keep. A sighing wind whispers over the walls. In contrast to the desolate loneliness of Montségur castle, Mirepoix is a bustling market town. Pastel coloured, half-timbered houses above wood frame arcades line the main square. Gargoyles on the church supervise the crowds around the curlicue adorned market. At the other end of the square sits the 14th century town hall. Each decorative wooden beam has a different carved head, demon, or animal.

In contrast to the desolate loneliness of Montségur castle, Mirepoix is a bustling market town. Pastel coloured, half-timbered houses above wood frame arcades line the main square. Gargoyles on the church supervise the crowds around the curlicue adorned market. At the other end of the square sits the 14th century town hall. Each decorative wooden beam has a different carved head, demon, or animal. On the opposite end of the spectrum from Montségur’s crumbling castle are the immaculately restored walls, bastions, and towers of Carcassonne’s Cité. Viewed across vineyards, the fortress stands as if from a fairy tale. Fortified since Roman times, Carcassonne was a Cathar stronghold in the Middle Ages. In the 1800s, Viollet-le-Duc imaginatively restored the double walls and the chateau they shelter. At a time when so many of France’s monuments were being neglected, he rallied for restoration. The project took fifty years and sadly, he did not live to see its glorious completion.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from Montségur’s crumbling castle are the immaculately restored walls, bastions, and towers of Carcassonne’s Cité. Viewed across vineyards, the fortress stands as if from a fairy tale. Fortified since Roman times, Carcassonne was a Cathar stronghold in the Middle Ages. In the 1800s, Viollet-le-Duc imaginatively restored the double walls and the chateau they shelter. At a time when so many of France’s monuments were being neglected, he rallied for restoration. The project took fifty years and sadly, he did not live to see its glorious completion.

Inside the fortress, crowded narrow streets are lined with souvenir stands, restaurants, and half-timbered houses. I wander past patrons dining at tables under a leafy canopy, artists painting water colours and children in crusader outfits brandishing plastic swords. Two falconers, with their beady-eyed charges gripping their leather-gloved arms, add to the medieval atmosphere. On the grass lices between the long inner and outer sheer rock walls, I stroll in relative solitude past black slate roofed towers and square cut bastions. Carcassonne is a World Heritage Site and the fortress, while impressive by day, is stunningly lit at night. As the evening sky fades to a dusky blue and the spotlights come on, the fairy tale towers and walls glow golden. I readily imagine a centurion slowly patrolling the walls.

Inside the fortress, crowded narrow streets are lined with souvenir stands, restaurants, and half-timbered houses. I wander past patrons dining at tables under a leafy canopy, artists painting water colours and children in crusader outfits brandishing plastic swords. Two falconers, with their beady-eyed charges gripping their leather-gloved arms, add to the medieval atmosphere. On the grass lices between the long inner and outer sheer rock walls, I stroll in relative solitude past black slate roofed towers and square cut bastions. Carcassonne is a World Heritage Site and the fortress, while impressive by day, is stunningly lit at night. As the evening sky fades to a dusky blue and the spotlights come on, the fairy tale towers and walls glow golden. I readily imagine a centurion slowly patrolling the walls.

If You Go:

If You Go:

It’s Remembrance Day, 2014 and I’m interlocking the sleeves of my parents’ Air Force jackets. They are arm in arm once more, laid out on the bed. Mum, a coding and deciphering officer with the RAF, and Dad, an air observer/navigator with the 10th Squadron, Bomber Command, met at a dance in Gander, Newfoundland in December, 1944. They’d both already served five long years. I salute them. Then I hug their blue-gray wool serge, touch their caps, and straighten their belts.

It’s Remembrance Day, 2014 and I’m interlocking the sleeves of my parents’ Air Force jackets. They are arm in arm once more, laid out on the bed. Mum, a coding and deciphering officer with the RAF, and Dad, an air observer/navigator with the 10th Squadron, Bomber Command, met at a dance in Gander, Newfoundland in December, 1944. They’d both already served five long years. I salute them. Then I hug their blue-gray wool serge, touch their caps, and straighten their belts.

A visit to Notre-Dame Cathedral’s Romanesque and Norman-Gothic edifice which pre-dates Mont-Saint-Michel was a must-see. It was consecrated in the fourth-century and flourished in King William’s reign. Its façade, chapter-house labyrinth, choir, as well as its fifteenth-century frescoes of angel musicians in the crypt, all captivate.

A visit to Notre-Dame Cathedral’s Romanesque and Norman-Gothic edifice which pre-dates Mont-Saint-Michel was a must-see. It was consecrated in the fourth-century and flourished in King William’s reign. Its façade, chapter-house labyrinth, choir, as well as its fifteenth-century frescoes of angel musicians in the crypt, all captivate. A yearning to be in the open air brings us to Velos Location: We rent bikes for eight hours at 16 Euros apiece and are transported to countryside where we hear the farmer’s tractor mowing hay. Or are those really tanks approaching? The trees that line the roads look mature, but aren’t they uniformly pushing the seventy years since peace was brokered? In 1944, trees provided fuel or defensive barriers on low-tide beaches, and their removal meant less shelter for an enemy. Today, those same trees flicker from shadow to light like newsreels, transmitting ticker tape noises to our spokes, and crank us forward.

A yearning to be in the open air brings us to Velos Location: We rent bikes for eight hours at 16 Euros apiece and are transported to countryside where we hear the farmer’s tractor mowing hay. Or are those really tanks approaching? The trees that line the roads look mature, but aren’t they uniformly pushing the seventy years since peace was brokered? In 1944, trees provided fuel or defensive barriers on low-tide beaches, and their removal meant less shelter for an enemy. Today, those same trees flicker from shadow to light like newsreels, transmitting ticker tape noises to our spokes, and crank us forward. We chance upon the British Cemetery of War Graves of Bazenville-Ryes en route to Juno. Among its nearly 1000 souls, it shares the high ground with British, American, Canadian and German soldiers. The only borders here are lovely weed-free plantings of roses, oregano and lavender.

We chance upon the British Cemetery of War Graves of Bazenville-Ryes en route to Juno. Among its nearly 1000 souls, it shares the high ground with British, American, Canadian and German soldiers. The only borders here are lovely weed-free plantings of roses, oregano and lavender. Longues-sur-Mer, the German Battery, still houses a 150-millimeter gun and four bunkers. Martine conducts the tour of the only battery to retain its original naval gun. These powerful long-range guns could have devastated had they functioned properly. The four guns were up, ready and firing over the 20-kilometer range, but a sand dune blocked the telescopic view for the shiny new range-finder still in its box. Without a range-finder, the guns fired blindly like big barking dogs, until direct hits silenced two of them just before the surrender.

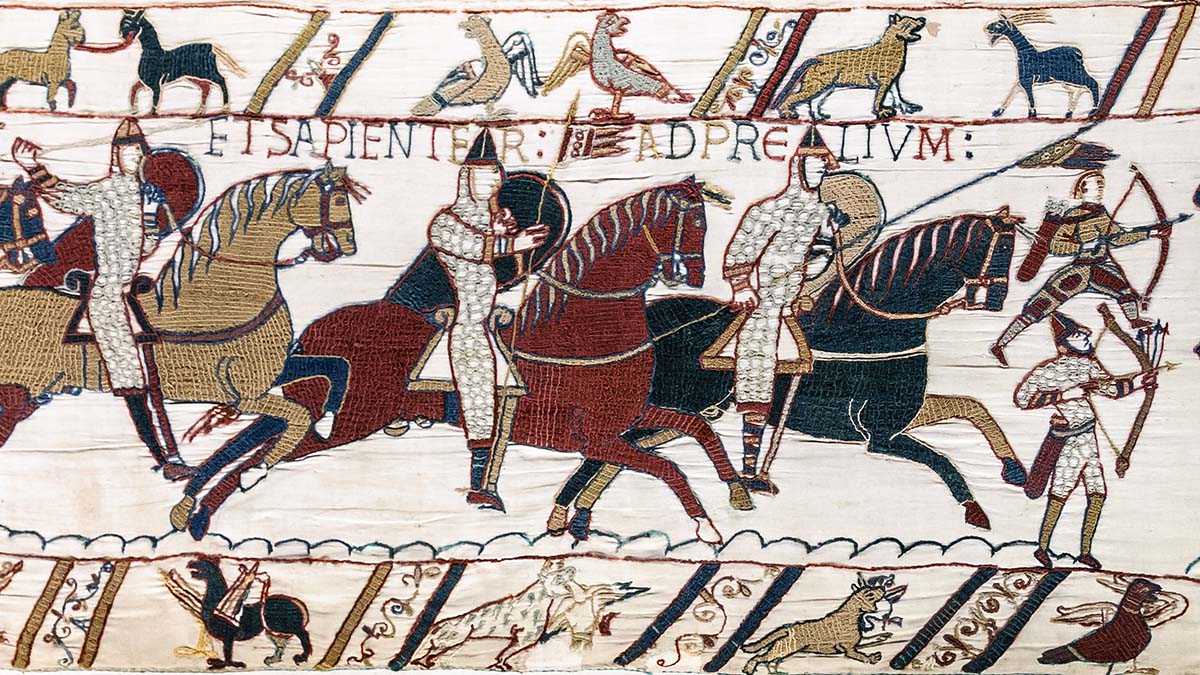

Longues-sur-Mer, the German Battery, still houses a 150-millimeter gun and four bunkers. Martine conducts the tour of the only battery to retain its original naval gun. These powerful long-range guns could have devastated had they functioned properly. The four guns were up, ready and firing over the 20-kilometer range, but a sand dune blocked the telescopic view for the shiny new range-finder still in its box. Without a range-finder, the guns fired blindly like big barking dogs, until direct hits silenced two of them just before the surrender. This summer, 2014, we visited Portsmouth’s D-Day Museum to view the recently-completed Overlord Tapestry that commemorates D-Day. I met Mary Turner Verrier, a 91-year-old Red Cross Nurse and veteran of Dieppe, Dunkirk and D-Day. Mary treated casualties of war, both civilians and servicemen, primarily for flash burns.

This summer, 2014, we visited Portsmouth’s D-Day Museum to view the recently-completed Overlord Tapestry that commemorates D-Day. I met Mary Turner Verrier, a 91-year-old Red Cross Nurse and veteran of Dieppe, Dunkirk and D-Day. Mary treated casualties of war, both civilians and servicemen, primarily for flash burns.