by Millie Stavadou

A beautiful but often overlooked corner of the world lies waiting to be discovered in North Wales. Tucked away in the region of Snowdonia lies Dolgellau and its surrounding area.

In search of peace and quiet, I traveled there at Easter, but of course any time of year is good. I stayed with my family in a little stone cottage outside the town of Dolgellau. The cottage was the first source of delight. It was converted from an old 16th century farm building, and although it has been fitted up with modern conveniences – there is no way I would stay anywhere without electricity! – it has kept much of the original character of the place.

In search of peace and quiet, I traveled there at Easter, but of course any time of year is good. I stayed with my family in a little stone cottage outside the town of Dolgellau. The cottage was the first source of delight. It was converted from an old 16th century farm building, and although it has been fitted up with modern conveniences – there is no way I would stay anywhere without electricity! – it has kept much of the original character of the place.

The cottage was in a beautiful setting, with simply marvelous views – who can beat the majestic sight of a mountain rising in the distance?

The cottage was in a beautiful setting, with simply marvelous views – who can beat the majestic sight of a mountain rising in the distance?

This meant, of course, that it was an ideal place to go walking, which of course we did. Plenty of space for the children to caper about, while we took things at a more leisurely pace, to enjoy the scenery as well as the exercise. There was an enjoyable walk on the first day, when we simply set out on foot from the cottage across the green landscape with a picnic. It was a beautiful day, and we just wanted to enjoy the fresh air and take in the sight and smell of the place. There was a great sense of peace and serenity all around, punctuated by the occasional cry of a bird or a nearby chirrup.

Walking is as walking does, of course, but we didn’t want to do that every day. We took the opportunity to explore the nearby town of Dolgellau, about 3 miles, or 5 minutes drive away. This is an ancient town, with history groaning from every corner, seeping from the very walls. The remains of a fort dating back to the days of the Romans have been found nearby, although this is not yet open to visitors.

We were determined to experience something of the long history of the town, starting with a visit to the great ruined arches of Cymer Abbey, [TOP PHOTO] founded there in 1198. It was a bit of a walk from the town, around two miles, but we had set off early and had plenty of time, so since it was a lovely day, off we went. It was very interesting to see the sight. The abbey remains are quite substantial, and it is easy to picture in the mind’s eye how it might once have been.

Back at Dolgellau, we were in the mood for a traditional tea, and we found just the place. A lovely little tea shop that used to be an ironmongery, with many of the old fixtures and fittings retained. A perfect setting for our traditional cream tea with home baked scones, local blackberry jam and a hot pot of tea. Who could ask for more?

Back at Dolgellau, we were in the mood for a traditional tea, and we found just the place. A lovely little tea shop that used to be an ironmongery, with many of the old fixtures and fittings retained. A perfect setting for our traditional cream tea with home baked scones, local blackberry jam and a hot pot of tea. Who could ask for more?

There it was among a pile of leaflets beside the till that we learned of what would form the basis of our activity for the following day: the Quaker Trail. Quakers, it transpires, once had a strong community in Dolgellau, and were persecuted for their faith. Today, you can follow in their footsteps around the town, walking through the pages of a novel that tells their story Y Stafell Ddirgel (The Secret Room) by Marion Eames. There is an organized walk through the key historical sites associated with the Quakers, encompassing the ducking stool, the site of the jail where Quakers were incarcerated for their beliefs, the home of Rowland Ellis, a key Quaker who emigrated to Pennsylvania, Cabel Tabor, the first Quaker Meeting House in the area, and another, Tyddyn Garreg, also the site of the Quaker burial ground. If you go on the organised tour, much will be explained of the history along the way. One usually associates ducking stools and witch trials with such places as Salem, so it was fascinating to discover this dark part of Welsh history.

After a couple of days spent in Dolgellau, we decided to change direction. Off we went to Blaenau and the unexpected treat of its steam railway. This was a matter of half an hour’s drive from where we were staying, and we were glad that we had hired a car for a few days, as it was well worth it. Blaenau is another historical town, but of another sort. This was the site of the famous slate mines that sent slate all around the world. Today it is a pretty little town, also with its share of tea shops. Don’t be surprised if the language you hear spoken around you there is not English, for this is still a stronghold of the Welsh language, the beautiful Celtic tongue spoken in the British isles long before the Germanic tribes first landed, bringing with them the languages that would later evolve into English. Welsh is a very different sort of tongue, soft on the ears and a musical pleasure to listen to.

After a couple of days spent in Dolgellau, we decided to change direction. Off we went to Blaenau and the unexpected treat of its steam railway. This was a matter of half an hour’s drive from where we were staying, and we were glad that we had hired a car for a few days, as it was well worth it. Blaenau is another historical town, but of another sort. This was the site of the famous slate mines that sent slate all around the world. Today it is a pretty little town, also with its share of tea shops. Don’t be surprised if the language you hear spoken around you there is not English, for this is still a stronghold of the Welsh language, the beautiful Celtic tongue spoken in the British isles long before the Germanic tribes first landed, bringing with them the languages that would later evolve into English. Welsh is a very different sort of tongue, soft on the ears and a musical pleasure to listen to.

Blaenau, or Blaenau Ffestiniog to give it the full name, is home to a steam railway. Yes, a real one, not a tiny one for small children. You can travel in the original first class carriages, once reserved for the upper crust of society, and this is exactly what we did. The train takes you on a circuit of Snowdonia, going through the mountains and gorgeous landscapes. It really is like taking a step back in the past – and the children said it felt like they were riding on Thomas the Tank Engine!

Back to our walking the next day, we decided to drive for a couple of miles and start our walk from another spot, to see something different. We were to be well rewarded with the beautiful view of Cregennen Lake. Looking out over the water, it was easy to see how the great myths and legends of our forebears arose. I could well picture a hand rising up through the mist shrouded waters of just such a lake, or imagine water spirits and goddesses of the land.

Back to our walking the next day, we decided to drive for a couple of miles and start our walk from another spot, to see something different. We were to be well rewarded with the beautiful view of Cregennen Lake. Looking out over the water, it was easy to see how the great myths and legends of our forebears arose. I could well picture a hand rising up through the mist shrouded waters of just such a lake, or imagine water spirits and goddesses of the land.

For the more active and sporty visitor, there are activities such as white water rafting and mountain biking, but these were not for us. We preferred to ramble and take picnics on leisurely days out in the countryside, for which we were well rewarded with the views. This is a place well worth visiting, and largely undiscovered.

If You Go:

Ffestiniog Railway

Where to Stay:

5-Day Heart of England Tour from London: North Wales, Stratford-upon-Avon, Buxton and York

About the author:

Millie Slavidou is a writer and a translator. As well as being a frequent contributor to Jump Mag, she is the author of the InstaExplorer series for pre-teens, which takes young readers on a journey round the world, experiencing local cultures, traditions and languages along the way. jumpbooks.co.uk/category/millie-slavidou

Photo credits:

Cymer Abbey by Penny Mayes / Cymer Abbey

All other photos are by Millie Slavidou:

View of cottage

Old Drover’s path near cottage

Mawddach Estuary from precipice walk

Cader Idris in the distance

Cregennen Lake

The city of Oxford is spread out before me as I stand on the tower parapet of the Church of St. Mary the Virgin. The staircase is a narrow, twisting spiral, challenging to manoeuvre as I squeezed past people who were coming down. The climb is one hundred and twenty four steps to get to the walkway just below the spire, but once up there I can see a complete three hundred and sixty degree view of Oxford. The buildings are nestled very closely together, made of honey-coloured limestone lit up in the sunshine. It is breezy at the top. I tie my scarf more tightly so that it won’t blow off and flutter over the wall. The stone figures on the walls play tricks on my eyes and look like they are about to crawl down to the next level. They have postures like Gollum crouching, ready to leap from place to place.

The city of Oxford is spread out before me as I stand on the tower parapet of the Church of St. Mary the Virgin. The staircase is a narrow, twisting spiral, challenging to manoeuvre as I squeezed past people who were coming down. The climb is one hundred and twenty four steps to get to the walkway just below the spire, but once up there I can see a complete three hundred and sixty degree view of Oxford. The buildings are nestled very closely together, made of honey-coloured limestone lit up in the sunshine. It is breezy at the top. I tie my scarf more tightly so that it won’t blow off and flutter over the wall. The stone figures on the walls play tricks on my eyes and look like they are about to crawl down to the next level. They have postures like Gollum crouching, ready to leap from place to place. He smiles mischievously. “It is actually called Hertford Bridge and looks more like the Rialto Bridge in Venice. They are often confused. When we get back down to ground level, shall we hunt for a place to eat?” Kevin suggests.

He smiles mischievously. “It is actually called Hertford Bridge and looks more like the Rialto Bridge in Venice. They are often confused. When we get back down to ground level, shall we hunt for a place to eat?” Kevin suggests.

I walked with my family down the cobblestone streets to a charming pub called “The Eagle and Child”. The building is lopsided due to its age, and several additions have been made to it over time, so the rooms are angled in odd ways. The little nooks and crannies have intimate spaces filled with small tables and chairs arranged for private conversations and philosophical discussions. The walls are covered with paintings and sketches of famous personages like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. I was in awe that I walked on the floor and sat in the building where these creators of famous literature regularly met.

I walked with my family down the cobblestone streets to a charming pub called “The Eagle and Child”. The building is lopsided due to its age, and several additions have been made to it over time, so the rooms are angled in odd ways. The little nooks and crannies have intimate spaces filled with small tables and chairs arranged for private conversations and philosophical discussions. The walls are covered with paintings and sketches of famous personages like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. I was in awe that I walked on the floor and sat in the building where these creators of famous literature regularly met. “Good afternoon everyone and welcome to the Bodleian Library.” The guide greets us and beckons the group to come closer. “You are probably curious about my accent. You can tell that I am not from here, I am American. I came to Oxford for a visit several years ago and fell in love with the city.” She says with a warm smile. “I decided that I wanted to be a part of it, so I am a volunteer in the Bodleian and give tours. I am excited to begin and share as much information about it as I can in this brief hour. Let’s begin, this room was used as the hospital in the Harry Potter movies.” She keenly announces.

“Good afternoon everyone and welcome to the Bodleian Library.” The guide greets us and beckons the group to come closer. “You are probably curious about my accent. You can tell that I am not from here, I am American. I came to Oxford for a visit several years ago and fell in love with the city.” She says with a warm smile. “I decided that I wanted to be a part of it, so I am a volunteer in the Bodleian and give tours. I am excited to begin and share as much information about it as I can in this brief hour. Let’s begin, this room was used as the hospital in the Harry Potter movies.” She keenly announces. Across the square from the Bodleian is the Sheldonian Theatre built by Sir Christopher Wren. To my surprise the theatre is not used to perform plays, but hosts concerts and degree ceremonies.

Across the square from the Bodleian is the Sheldonian Theatre built by Sir Christopher Wren. To my surprise the theatre is not used to perform plays, but hosts concerts and degree ceremonies.

Arriving from the south, Robin Hood’s Bay is visible miles away; from a jutting limestone headland just past Ravenscar, one of a few villages on the walk. The approach to Robin Hood’s Bay at low tide is on a long stretch of sandy beach, with some rocks and pools along the way. The sea covers most of the beach at high tide; reuniting with the high cliffs in the evening like a blanket being tucked between bed and wall.

Arriving from the south, Robin Hood’s Bay is visible miles away; from a jutting limestone headland just past Ravenscar, one of a few villages on the walk. The approach to Robin Hood’s Bay at low tide is on a long stretch of sandy beach, with some rocks and pools along the way. The sea covers most of the beach at high tide; reuniting with the high cliffs in the evening like a blanket being tucked between bed and wall. The age of Robin Hood’s Bay is unknown, as it was a thriving village of fifty cottages when first recorded in 1540 by Leland, King Henry VIII’s topographer. In the following century it was recorded on Dutch sea charts, which omitted Whitby; RHB’s now much larger northern neighbour. The origins of RHB’s name are also unclear, with no recorded reference to the famous outlaw of Sherwood Forest. That legend did become popular in the 15th century though, with the first recorded ballad dated to 1450, around the same time that the Yorkshire village was thought to be growing. If Robin Hood was the John Lennon of his time, then it seems likely that people would want to name things after him. However, the local history society believe it is more likely that the name derived from ancient woodland spirits, such as Robin Goodfellow, who preceded the now more famous Medieval rebel, and may have played a part in creating the green Sherwood Forest legend, rather than Hood influencing other contemporary things.

The age of Robin Hood’s Bay is unknown, as it was a thriving village of fifty cottages when first recorded in 1540 by Leland, King Henry VIII’s topographer. In the following century it was recorded on Dutch sea charts, which omitted Whitby; RHB’s now much larger northern neighbour. The origins of RHB’s name are also unclear, with no recorded reference to the famous outlaw of Sherwood Forest. That legend did become popular in the 15th century though, with the first recorded ballad dated to 1450, around the same time that the Yorkshire village was thought to be growing. If Robin Hood was the John Lennon of his time, then it seems likely that people would want to name things after him. However, the local history society believe it is more likely that the name derived from ancient woodland spirits, such as Robin Goodfellow, who preceded the now more famous Medieval rebel, and may have played a part in creating the green Sherwood Forest legend, rather than Hood influencing other contemporary things.

The area does seem to have thrived on independence from outside control and taxes, as the legendary Robin Hood did, with the local history society writing there is no doubt that Robin Hood’s Bay was the busiest smuggling village on the Yorkshire coast by the 18th century. That coastal culture was made famous in the

The area does seem to have thrived on independence from outside control and taxes, as the legendary Robin Hood did, with the local history society writing there is no doubt that Robin Hood’s Bay was the busiest smuggling village on the Yorkshire coast by the 18th century. That coastal culture was made famous in the  Smuggling was not the only activity dividing village and rulers, as on the other side there was something that looks even more evil in history: Press Gangs were sent into villages such as Robin Hood’s Bay to find and kidnap men for the Royal Navy. Those pressed into service were unlikely to return. It is easy to imagine the drama of the 18th century in the compact steep closely-knit village that still structurally exists, with contraband passed through windows from harbour to hilltop without touching the ground; or the women banging drums when Press Gangs were spotted, and the men running to hide.

Smuggling was not the only activity dividing village and rulers, as on the other side there was something that looks even more evil in history: Press Gangs were sent into villages such as Robin Hood’s Bay to find and kidnap men for the Royal Navy. Those pressed into service were unlikely to return. It is easy to imagine the drama of the 18th century in the compact steep closely-knit village that still structurally exists, with contraband passed through windows from harbour to hilltop without touching the ground; or the women banging drums when Press Gangs were spotted, and the men running to hide. When I finished my walk from Scarborough I had to find the campsite a couple of miles farther north of the village. After stopping to take too many photos it was totally dark by then, but I was compensated by a clear night providing an amazing countryside view of the sky, after becoming used to inner city light pollution skies. Looking upwards at regular intervals for long periods of time delayed me further, but as Downhill showed, it’s not all about keeping to time, but what you see and learn along the way.

When I finished my walk from Scarborough I had to find the campsite a couple of miles farther north of the village. After stopping to take too many photos it was totally dark by then, but I was compensated by a clear night providing an amazing countryside view of the sky, after becoming used to inner city light pollution skies. Looking upwards at regular intervals for long periods of time delayed me further, but as Downhill showed, it’s not all about keeping to time, but what you see and learn along the way.

Instead, I walked back to Whitby, completing another section of the Cleveland Way. Staithes is ten miles above the town famous for Dracula’s fictional landing in England, while Robin Hood’s Bay is five miles below. As with my walk from Scarborough, I took too many photos and made slower progress than planned. Thankfully, I reached Whitby fifteen minutes before the last bus back to Leeds.

Instead, I walked back to Whitby, completing another section of the Cleveland Way. Staithes is ten miles above the town famous for Dracula’s fictional landing in England, while Robin Hood’s Bay is five miles below. As with my walk from Scarborough, I took too many photos and made slower progress than planned. Thankfully, I reached Whitby fifteen minutes before the last bus back to Leeds.

Ilkley is a picturesque town in the Wharfe Valley, with the Wharfe river on its eastern side, and a rock plateau rising above the western. The latter is known as Ilkley Moor, and is the subject of Yorkshire’s unofficial anthem, On Ilkla Moor Baht ‘at. The song is about a man courting a woman while questioning her decision to walk on the moor without a hat – bar hat. The first published version of the song dates from 1916, so it is a century old this year; although it is thought to have been sung as a folk song for a couple of generations before being written down. The Cow and Calf rocks on the southern edge of the moor are popular landmarks, as well as providing small sheer cliff-faces to climb.

Ilkley is a picturesque town in the Wharfe Valley, with the Wharfe river on its eastern side, and a rock plateau rising above the western. The latter is known as Ilkley Moor, and is the subject of Yorkshire’s unofficial anthem, On Ilkla Moor Baht ‘at. The song is about a man courting a woman while questioning her decision to walk on the moor without a hat – bar hat. The first published version of the song dates from 1916, so it is a century old this year; although it is thought to have been sung as a folk song for a couple of generations before being written down. The Cow and Calf rocks on the southern edge of the moor are popular landmarks, as well as providing small sheer cliff-faces to climb.

Skipton Castle was built in 1090 by Normans who had recently defeated Anglo-Saxon King Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Hastings is in the south of England, and one of the reasons for Harold’s defeat is that many in his army had only just returned from defeating a Viking invasion led by Harald Hardrada and Tostig in the east Yorkshire Battle of Stamford Bridge.

Skipton Castle was built in 1090 by Normans who had recently defeated Anglo-Saxon King Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Hastings is in the south of England, and one of the reasons for Harold’s defeat is that many in his army had only just returned from defeating a Viking invasion led by Harald Hardrada and Tostig in the east Yorkshire Battle of Stamford Bridge. The last Clifford, Lady Anne, planted the yew tree that still stands in the Tudor-era Conduit courtyard. It is a fine sight on a sunny summer day, with its greenery rising high enough atop a twisting trunk to feel the warmth of sky above the castle walls.

The last Clifford, Lady Anne, planted the yew tree that still stands in the Tudor-era Conduit courtyard. It is a fine sight on a sunny summer day, with its greenery rising high enough atop a twisting trunk to feel the warmth of sky above the castle walls.

Skipton is the local gateway to the Yorkshire Dales National Park, with buses weaving out from the town along country lanes to picturesque stone-built villages. A few miles from Skipton is Malham. The small village is famous for its 260-feet high limestone cove and paving, which was the setting for a scene in Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows Part 1.

Skipton is the local gateway to the Yorkshire Dales National Park, with buses weaving out from the town along country lanes to picturesque stone-built villages. A few miles from Skipton is Malham. The small village is famous for its 260-feet high limestone cove and paving, which was the setting for a scene in Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows Part 1. There is evidence of 4000-year-old buildings on Ingleborough, and the second part of its name derives from burh, an Old English word for a fortified place. It has been assumed for years that it was a hillfort village, but an information board on one of its paths advises that a newer theory argues it could have been a special location for spiritual occasions, like Stonehenge in the south.

There is evidence of 4000-year-old buildings on Ingleborough, and the second part of its name derives from burh, an Old English word for a fortified place. It has been assumed for years that it was a hillfort village, but an information board on one of its paths advises that a newer theory argues it could have been a special location for spiritual occasions, like Stonehenge in the south.

by John Thomson

by John Thomson I’m in Glasgow visiting relatives, recalled to the city by blood ties and circumstance. Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city, a little shabby in parts I must admit, its once busy dockyards replaced by a shopping mall, an amusement centre and a transportation museum. Thankfully, many of Glasgow’s magnificent sandstone buildings remain intact, a reminder of its better days when the city was flush with pride and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was at the top of his game. The Mackintosh story, like the city itself, is a bittersweet tale of success, decline and ultimate redemption. Not familiar with the name? You’ll recognize his furniture. His straight, high-backed chairs are cultural icons often associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement and although I’m not a fan of his chairs – too rigid for me – I have to acknowledge their importance.

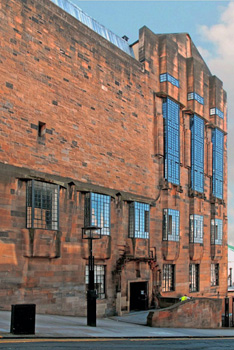

I’m in Glasgow visiting relatives, recalled to the city by blood ties and circumstance. Glasgow is Scotland’s largest city, a little shabby in parts I must admit, its once busy dockyards replaced by a shopping mall, an amusement centre and a transportation museum. Thankfully, many of Glasgow’s magnificent sandstone buildings remain intact, a reminder of its better days when the city was flush with pride and Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was at the top of his game. The Mackintosh story, like the city itself, is a bittersweet tale of success, decline and ultimate redemption. Not familiar with the name? You’ll recognize his furniture. His straight, high-backed chairs are cultural icons often associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement and although I’m not a fan of his chairs – too rigid for me – I have to acknowledge their importance. I start my Glasgow tour on Sauchiehall (pronounced Sock-ee-hall) Street and work my way west. Glasgow converted its two main downtown thoroughfares, Buchanan and Sauchiehall Streets into pedestrian malls years ago and getting around the central core is a pedestrian’s dream. A gentle rain sprinkles the pavement but as soon as it starts, it stops. I’m barely wet. I climb Scott Street to the Glasgow School of Art considered the pinnacle of Mackintosh’s architectural career. Completed in 1909, it’s an imposing structure with a domineering command of its surroundings. It reminds me of a fortress. The western wall is tight and dense with narrow loopholes from which I imagine the inhabitants, if they were medieval archers, could shoot arrows if the city were under siege. The northern wall on the other hand has lots of large windows giving it an airy feel and letting in lots of light too. After all, this is an art school. Form follows function.

I start my Glasgow tour on Sauchiehall (pronounced Sock-ee-hall) Street and work my way west. Glasgow converted its two main downtown thoroughfares, Buchanan and Sauchiehall Streets into pedestrian malls years ago and getting around the central core is a pedestrian’s dream. A gentle rain sprinkles the pavement but as soon as it starts, it stops. I’m barely wet. I climb Scott Street to the Glasgow School of Art considered the pinnacle of Mackintosh’s architectural career. Completed in 1909, it’s an imposing structure with a domineering command of its surroundings. It reminds me of a fortress. The western wall is tight and dense with narrow loopholes from which I imagine the inhabitants, if they were medieval archers, could shoot arrows if the city were under siege. The northern wall on the other hand has lots of large windows giving it an airy feel and letting in lots of light too. After all, this is an art school. Form follows function.

Mackintosh was not only an architect but a designer too and the original Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall is a prime example of his handiwork. Recruited by local businesswoman and teetotaller Catherine Cranston in 1896 to dress up her establishments, Mack designed everything – tables, chairs, room dividers, wall decorations, napkins and cutlery. The Tea Room, one of two in the city, has been preserved as a Mackintosh museum with the original stained glass door and replica furniture and yes, they still serve tea. Angularity is the prevailing theme – there are those high backed chairs again – and everything conforms to Mackintosh’s singular, unifying concept.

Mackintosh was not only an architect but a designer too and the original Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall is a prime example of his handiwork. Recruited by local businesswoman and teetotaller Catherine Cranston in 1896 to dress up her establishments, Mack designed everything – tables, chairs, room dividers, wall decorations, napkins and cutlery. The Tea Room, one of two in the city, has been preserved as a Mackintosh museum with the original stained glass door and replica furniture and yes, they still serve tea. Angularity is the prevailing theme – there are those high backed chairs again – and everything conforms to Mackintosh’s singular, unifying concept. I get off at the Kelvinhall stop and walk to the Hunterian Art Gallery on the grounds of the University of Glasgow. Mack’s 1906 residence or at least parts of it – the hall, dining room, living room and the main bedroom – have been moved from their original location and reassembled here for public display. It’s breathtaking in its simplicity. Mackintosh and Margaret have designed everything themselves right down to the fireplace decorations. They even knocked down interior walls to create more space, a radical innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Sunlight bounces off the stark white walls accentuating the open plan. The angular motif that I first saw at the Willow Tea Room, lots of right angles and variations on the square, is repeated in the floor, the furniture and the wall decorations. Everything is co-ordinated. A bit too co-ordinated. I feel like I’m in a museum piece, which of course I am, and long for the remains of a half-eaten breakfast on the dining room table or a pile of dirty clothes at the foot of those oh-so-perfect matching beds. I wonder if Mack and his wife ever felt the same way. Probably not. I have to admit the duo were ahead of their time though. Their turn-of-the-century digs look like they belonged in the 1930’s.

I get off at the Kelvinhall stop and walk to the Hunterian Art Gallery on the grounds of the University of Glasgow. Mack’s 1906 residence or at least parts of it – the hall, dining room, living room and the main bedroom – have been moved from their original location and reassembled here for public display. It’s breathtaking in its simplicity. Mackintosh and Margaret have designed everything themselves right down to the fireplace decorations. They even knocked down interior walls to create more space, a radical innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century. Sunlight bounces off the stark white walls accentuating the open plan. The angular motif that I first saw at the Willow Tea Room, lots of right angles and variations on the square, is repeated in the floor, the furniture and the wall decorations. Everything is co-ordinated. A bit too co-ordinated. I feel like I’m in a museum piece, which of course I am, and long for the remains of a half-eaten breakfast on the dining room table or a pile of dirty clothes at the foot of those oh-so-perfect matching beds. I wonder if Mack and his wife ever felt the same way. Probably not. I have to admit the duo were ahead of their time though. Their turn-of-the-century digs look like they belonged in the 1930’s. I learn that young Mackintosh was quite the celebrity when he completed the Glasgow School of Art in 1909 but when he left his employers, Honeyman and Keppie, to strike out on his own, tastes changed and his business faltered. He and his wife Margaret retreated to London to concentrate on textile design. And when that didn’t pan out the couple eventually retired to southern France where Mackintosh renounced architecture entirely and spent the rest of his life painting watercolours.

I learn that young Mackintosh was quite the celebrity when he completed the Glasgow School of Art in 1909 but when he left his employers, Honeyman and Keppie, to strike out on his own, tastes changed and his business faltered. He and his wife Margaret retreated to London to concentrate on textile design. And when that didn’t pan out the couple eventually retired to southern France where Mackintosh renounced architecture entirely and spent the rest of his life painting watercolours.

As I board the plane to return home, I ponder the Mackintosh phenomenon. Yes, his buildings are stunning. Built to withstand the Scottish climate, they’re solid, substantial structures in contrast to those flouncy neo-classical buildings in vogue at the time. Scholars have called the style Scottish Baronial, tying Mackintosh and his ideas to the Scottish Renaissance of the early twentieth century when there was a creative surge in Scottish arts and letters. Perhaps he deserves his fame because he stripped away superfluous decoration in favour of detail that complemented the building’s integrity, paving the way for Modernism. Perhaps it’s because he involved himself in total design – integrating architecture with wall treatments, light fixtures and furniture. Mack pre-dated future “starchitects” like Frank Gehry by decades. Perhaps it’s all of these things, a combination of accomplishments both historic and aesthetic.

As I board the plane to return home, I ponder the Mackintosh phenomenon. Yes, his buildings are stunning. Built to withstand the Scottish climate, they’re solid, substantial structures in contrast to those flouncy neo-classical buildings in vogue at the time. Scholars have called the style Scottish Baronial, tying Mackintosh and his ideas to the Scottish Renaissance of the early twentieth century when there was a creative surge in Scottish arts and letters. Perhaps he deserves his fame because he stripped away superfluous decoration in favour of detail that complemented the building’s integrity, paving the way for Modernism. Perhaps it’s because he involved himself in total design – integrating architecture with wall treatments, light fixtures and furniture. Mack pre-dated future “starchitects” like Frank Gehry by decades. Perhaps it’s all of these things, a combination of accomplishments both historic and aesthetic.