Florence, Italy

by Peppa Martin

Bands of Senegalese boys wander Florence selling fakes. From random perches around the city, they hawk all kinds of coveted trinkets — sunglasses with luxury brand logos up on the Piazzale Michelangelo, Mont Blanc pens near the Bargello, Tiffany bracelets along the Arno’s bridges. Sometimes, they spread out their seductive goodies right under the official government-installed “Don’t Buy Fakes” sign in the sprawling Piazza Della Repubblica.

I am amused and entertained by the wooing of passersby that ensues, the waltz of gestures and pivots, the come-hither looks. Economic casualty aside, I presume the pride of owning an un-Burberry outweighs the pesky oppression of jail. Yesterday, I watched as they installed themselves in front of the Prada store, selling fake Prada bags. Some laugh, some applaud, I cringe.

I am amused and entertained by the wooing of passersby that ensues, the waltz of gestures and pivots, the come-hither looks. Economic casualty aside, I presume the pride of owning an un-Burberry outweighs the pesky oppression of jail. Yesterday, I watched as they installed themselves in front of the Prada store, selling fake Prada bags. Some laugh, some applaud, I cringe.

When word of approaching polizia comes via cell phone relay from their cohort scouts, they quickly roll everything up in woven blankets, and with lightning speed disappear down narrow alleyways. I understand this is a tedious, daily war between the cat army and mouse rebels– complete with sorties, offensives, strategies, troops and embedded spies.

Rashid tells me he came from Marrakesh a couple of years ago. He is 25 and comes every day to the Palazzo Vecchio to surreptitiously sell cheap posters depicting iconic artworks hanging in Italian museums. With knitted brow and eyes cast to the clouds, he proceeds to say that on a good day he’ll sell 10 or 20 at five euros each. He leans in closer and whispers to me, proudly, his biggest seller is Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’.

Rashid tells me he came from Marrakesh a couple of years ago. He is 25 and comes every day to the Palazzo Vecchio to surreptitiously sell cheap posters depicting iconic artworks hanging in Italian museums. With knitted brow and eyes cast to the clouds, he proceeds to say that on a good day he’ll sell 10 or 20 at five euros each. He leans in closer and whispers to me, proudly, his biggest seller is Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’.

This, on most days, he sells right under sweet Venus’s nose in front of the Uffizi Gallery where she hangs.

Today, that smart cookie Venus would have locked down her rights, copyrights, licenses, trademarks, proprietary website and endorsement contracts in perpetuity..

I pass legitimate kiosk vendors in the Piazza Della Signoria who sell miniature copies of Michelangelo’s monolithic ‘David’, right in front of the monolithic fake David which was installed in the former spot of the real David which was moved indoors to the Accademia Gallery to protect it from weather and depraved nutjobs. Now the fake David gets vandalized by wallclimbers, counter-culturists and ignoramus graffiti-taggers.

I learn the real David, though housed in a quiet museum, has been attacked a few times, recently by a hammer-wielding fanatic. It was repaired by marble restorers, so is it disqualified from being truly real?

I learn the real David, though housed in a quiet museum, has been attacked a few times, recently by a hammer-wielding fanatic. It was repaired by marble restorers, so is it disqualified from being truly real?

Da Vinci was an illegitimate child — is he disqualified too? I’m told he was later referred to as a ‘Native Son’, in an effort to cloak the shame of his status in more respectable terms.

We are awash in fakes, copies, imitations, lies, faux this, ersatz that, imposters, replicas, reproductions and simulated, airbrushed, retouched bogus posturing phoneys.

From derivatives to lovers, the world is full of Great Pretenders.

It was Anna Maria Luisa di Medici who, upon her death in 1642 decreed that all Florentine art and artifacts be retained in Italy for the benefit of the public. Thus, with great foresight, she preserved the country’s great works of art from sale abroad or theft by rival dynasties.

The real ones, mercifully, are still here — proof that authenticity does exist.

You can feel it too, because they emanate a near-imperceptible low-grade hum of exquisite grace.

And this, I accept, briefly satisfies the elusive quest for the real thing.

Florence Art and Street Food WalkingTour

If You Go:

Plan an easy day trip to ‘Il Palagio’, one of Tuscany’s most famous 14th century castles, which has produced wine and olive oil for the past 300 years. Originally owned by the Visdomini family, it became a fortress in the 15th century of the Repubblica Fiorentina for two centuries. Later, the City of Florence gave the castle to the Miniati family, who own the property to this day.

The splendid gardens are thanks to the Grand Duke of Habsburg-Lorena, and features a Cypress of Lebanon planted by a Napoleonic official. One can visit the resplendent, self-contained chapel adorned with frescoes, and then traverse to the chilly, damp subterranean dungeon cum cellar that today is home to huge oak barrels aging the eponymous Chianti Classico wines.

Private Tour: The Art of Living in Florence in the Renaissance with Exclusive Private Palace Visit

About the author:

Peppa is a full time professional photographer and gallerist, living in Vancouver BC. She runs her own business, “truth and beauty,” a commercial studio and boutique gallery of contemporary photography. www.truthandbeauty.ca Peppa is interested in ideas, people, art, places, design, architecture and gardens; loves to cook, read, dance, and be with family and friends. Her (fab) four adult children are strewn around the globe on three continents. Follow Peppa on twitter @4truthandbeauty and at instagram.com/pepstagrams

All photos are by Peppa Martin and Terri Fogarty (San Florenzo Market scene)

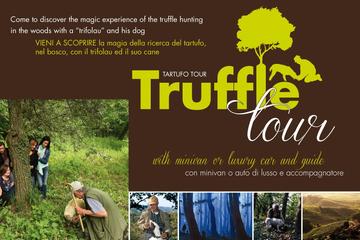

What faithfully happens, as summer turns to autumn in Tuscany, is that people come down with a pernicious fever – let’s call it ‘acute funghiosis’ – which causes a delirious devotion to truffles. Truffles are discussed with the same intensity and fervor usually reserved for Plato. They are hunted, worshipped, prized, prepared and savoured — after which, the experience of hunting, worshipping, prizing, preparing and savoring is again examined with near-religious ecstasy. This epidemic grips the palate of anyone who eats, and can be cured foremost with a generous serving of taglierini alla tartufo.

What faithfully happens, as summer turns to autumn in Tuscany, is that people come down with a pernicious fever – let’s call it ‘acute funghiosis’ – which causes a delirious devotion to truffles. Truffles are discussed with the same intensity and fervor usually reserved for Plato. They are hunted, worshipped, prized, prepared and savoured — after which, the experience of hunting, worshipping, prizing, preparing and savoring is again examined with near-religious ecstasy. This epidemic grips the palate of anyone who eats, and can be cured foremost with a generous serving of taglierini alla tartufo. Now, this is also Olive Oil season, with capital ‘O’ s , and everywhere you go is the promise of 42 extra-virgins in heaven. Hand picked, hand pressed, home bottled, first run, double extra, organic, small batch, cottage industry silken oil flows more vigorously and greener than the Arno. Beautiful handblown bottles with delicately drawn artisanal labels beckon you from shop windows and market stalls with their liquid treasure of early fresh earthen green oil. Sadly, by the time it hits our shores, its colour and flavour have mellowed and that newborn nutty taste is but a memory of the motherland.

Now, this is also Olive Oil season, with capital ‘O’ s , and everywhere you go is the promise of 42 extra-virgins in heaven. Hand picked, hand pressed, home bottled, first run, double extra, organic, small batch, cottage industry silken oil flows more vigorously and greener than the Arno. Beautiful handblown bottles with delicately drawn artisanal labels beckon you from shop windows and market stalls with their liquid treasure of early fresh earthen green oil. Sadly, by the time it hits our shores, its colour and flavour have mellowed and that newborn nutty taste is but a memory of the motherland. The next day, with late October sun on the city’s shoulders, I headed by local bus to the nearby borough of Fiesole, perched high in the emerald hills overlooking Florence. There is a spectacular hotel here, The Villa San Michele, of the Orient-Express group, that delivers luxurious vistas of the Florentine valley while dining al fresco. Skipping an overnight stay, I opted for the ‘express’ route of lunching like a local.

The next day, with late October sun on the city’s shoulders, I headed by local bus to the nearby borough of Fiesole, perched high in the emerald hills overlooking Florence. There is a spectacular hotel here, The Villa San Michele, of the Orient-Express group, that delivers luxurious vistas of the Florentine valley while dining al fresco. Skipping an overnight stay, I opted for the ‘express’ route of lunching like a local.

“Fair Verona” is brimming with historical and artistic treasures, such as the magnificent Arena, whose sands where once stained with the blood of gladiators, but now hosts one of the most spectacular opera festivals in the world.

“Fair Verona” is brimming with historical and artistic treasures, such as the magnificent Arena, whose sands where once stained with the blood of gladiators, but now hosts one of the most spectacular opera festivals in the world. The tunnel-like entrance to the courtyard is covered in graffiti and lovers traditionally leave their names, snippets of poetry or messages of love on panels that cover the walls, if they can find space, creating a fascinating collage dedicated to love.

The tunnel-like entrance to the courtyard is covered in graffiti and lovers traditionally leave their names, snippets of poetry or messages of love on panels that cover the walls, if they can find space, creating a fascinating collage dedicated to love. Behind the statue, the railings are covered in padlocks forming a chain created by lovers from all around the world. Couples write their names on padlocks, which can be bought from the handy gift shop, or bring their own, to write their names on and bind their love forever. This gimmick, which the cynical criticize as being solely a source of commercial profit, nevertheless creates a unique piece of living art, which is constantly changing. According to popular belief couples who leave messages on Juliet’s Wall, in any shape or form, will find eternal love.

Behind the statue, the railings are covered in padlocks forming a chain created by lovers from all around the world. Couples write their names on padlocks, which can be bought from the handy gift shop, or bring their own, to write their names on and bind their love forever. This gimmick, which the cynical criticize as being solely a source of commercial profit, nevertheless creates a unique piece of living art, which is constantly changing. According to popular belief couples who leave messages on Juliet’s Wall, in any shape or form, will find eternal love.

Perhaps Italians might disagree with me when I use this term, since this, the Cimitero Acattolico, is the last resting place for those who could not, or would not be buried in the traditional Catholic cemeteries here in the heart of Roman Catholicism. But hallowed it is, nonetheless, since this patch of land, overgrown with weeds and flowers, contains the remains of the some of the most important figures of the last few centuries: local dissidents and those from other lands, ex-pats, writers, revolutionaries, atheists and Jews who, famous or not, all came to rest together here in this painfully beautiful monument to non-conformity. Antonio Gramsci, Gregory Corso, and a cat named Romeo are some among this motley crew, though none of them hold higher places in the echelons of artistic memory than the two greats of English Romanticism buried here: John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. How could it not be raining, then? It was as if the luminous Roman sky had been replaced for a moment by a melancholy English one, pausing to weep a bit for two lost sons, entombed amidst the ruins, far far away.

Perhaps Italians might disagree with me when I use this term, since this, the Cimitero Acattolico, is the last resting place for those who could not, or would not be buried in the traditional Catholic cemeteries here in the heart of Roman Catholicism. But hallowed it is, nonetheless, since this patch of land, overgrown with weeds and flowers, contains the remains of the some of the most important figures of the last few centuries: local dissidents and those from other lands, ex-pats, writers, revolutionaries, atheists and Jews who, famous or not, all came to rest together here in this painfully beautiful monument to non-conformity. Antonio Gramsci, Gregory Corso, and a cat named Romeo are some among this motley crew, though none of them hold higher places in the echelons of artistic memory than the two greats of English Romanticism buried here: John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. How could it not be raining, then? It was as if the luminous Roman sky had been replaced for a moment by a melancholy English one, pausing to weep a bit for two lost sons, entombed amidst the ruins, far far away. Though their names are often intertwined, John Keats and Percy Shelley came to Italy for very different reasons. Shelley, the rebellious Etonian from an Aristocratic family, was leading a wild life, one easier experienced abroad. He was best friends with Lord Byron and romantically entangled with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (turned Shelley), the author of Frankenstein. His lifestyle, radical views, and writing had brought him not only fame, but also infamy. Like many writers and artists of his day, he was attracted to the warmth of the European south, to its classical pagan origins, and to that fact that he could live freely there, away from the scandals that plagued him in England. Keats, on the other hand, came to Italy to die.

Though their names are often intertwined, John Keats and Percy Shelley came to Italy for very different reasons. Shelley, the rebellious Etonian from an Aristocratic family, was leading a wild life, one easier experienced abroad. He was best friends with Lord Byron and romantically entangled with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (turned Shelley), the author of Frankenstein. His lifestyle, radical views, and writing had brought him not only fame, but also infamy. Like many writers and artists of his day, he was attracted to the warmth of the European south, to its classical pagan origins, and to that fact that he could live freely there, away from the scandals that plagued him in England. Keats, on the other hand, came to Italy to die.

Besides the cruelty inherent in this statement, the irony was palpable too. Keats’ medical training, no matter how practical it may have been, could do nothing to stop what was then an almost incurable disease, tuberculosis. Not long after his brother died, it became clear that John Keats had contracted the illness too. Knowing that he would not survive the English winter, his friends gathered whatever money they could in order to send him to a gentler climate, a last ditch attempt to save his life.

Besides the cruelty inherent in this statement, the irony was palpable too. Keats’ medical training, no matter how practical it may have been, could do nothing to stop what was then an almost incurable disease, tuberculosis. Not long after his brother died, it became clear that John Keats had contracted the illness too. Knowing that he would not survive the English winter, his friends gathered whatever money they could in order to send him to a gentler climate, a last ditch attempt to save his life. Shelley was buried in the same cemetery a mere year later, the victim of a violent Mediterranean storm that drowned him while sailing off the coast of northern Italy. A book of John Keats’ poetry was found in his pocket. Shelley’s cremated remains (all but his heart, which was kept by Mary Shelley and eventually buried in England) can be found under a small flat tombstone a short walk from Keats’, bearing the Latin “Cor Cordium” (heart of hearts), and a quote from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “Nothing of him that doth fade, But doth suffer a sea-change is to something rich and strange.”

Shelley was buried in the same cemetery a mere year later, the victim of a violent Mediterranean storm that drowned him while sailing off the coast of northern Italy. A book of John Keats’ poetry was found in his pocket. Shelley’s cremated remains (all but his heart, which was kept by Mary Shelley and eventually buried in England) can be found under a small flat tombstone a short walk from Keats’, bearing the Latin “Cor Cordium” (heart of hearts), and a quote from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “Nothing of him that doth fade, But doth suffer a sea-change is to something rich and strange.” On my own visit, while I sat there overcome with tears, I heard a rustling from the wall above me. From out of one of the vines came a black and white cat, who jumped down onto the bench, and then snuggled up onto my lap. Through my own teary-eyed haze and quixotic imagination, it was easy to believe that in that moment I was being visited by the spirit of the poet himself. Of course, as I got up to walk to Shelley’s grave, straight ahead and to the right, I realised that the cat was just one among many strays who live in the cemetery, and to whose livelihood you can also donate money. However, the impression stayed with me, there on that wet rainy day, as I wandered alone through the grounds of the Cimitero Acattolico. And I emphasize the word “alone”, because visitors here are many fewer than in other famous cemeteries such as Père Lachaise or in Roman tourist spots like Saint Peter’s. When Oscar Wilde visited in 1877, he called it “the holiest place in Rome”. There, breaking bread with the dead, it’s not hard to see why.

On my own visit, while I sat there overcome with tears, I heard a rustling from the wall above me. From out of one of the vines came a black and white cat, who jumped down onto the bench, and then snuggled up onto my lap. Through my own teary-eyed haze and quixotic imagination, it was easy to believe that in that moment I was being visited by the spirit of the poet himself. Of course, as I got up to walk to Shelley’s grave, straight ahead and to the right, I realised that the cat was just one among many strays who live in the cemetery, and to whose livelihood you can also donate money. However, the impression stayed with me, there on that wet rainy day, as I wandered alone through the grounds of the Cimitero Acattolico. And I emphasize the word “alone”, because visitors here are many fewer than in other famous cemeteries such as Père Lachaise or in Roman tourist spots like Saint Peter’s. When Oscar Wilde visited in 1877, he called it “the holiest place in Rome”. There, breaking bread with the dead, it’s not hard to see why.

My wife and I are on a Mediterranean cruise along the coasts of Italy and France celebrating our 20th anniversary, sailing on the ultra-deluxe Norwegian ship. Sea Dream I, which carries just over 100 passengers. Sea Dream I is a magic carpet, easing us in comfort and style through a region full of fascinating history. We have been anticipating visits to some wonderful ports and are not disappointed. What we had not foreseen, though, is the many ways that Napoleon, or perhaps just his spirit, would keep making his presence felt, as if popping up unexpectedly in little cameo appearances. These underscore just how completely he dominated Europe in his brief but dramatic era of war and conquest, supreme glory and abject defeat.

My wife and I are on a Mediterranean cruise along the coasts of Italy and France celebrating our 20th anniversary, sailing on the ultra-deluxe Norwegian ship. Sea Dream I, which carries just over 100 passengers. Sea Dream I is a magic carpet, easing us in comfort and style through a region full of fascinating history. We have been anticipating visits to some wonderful ports and are not disappointed. What we had not foreseen, though, is the many ways that Napoleon, or perhaps just his spirit, would keep making his presence felt, as if popping up unexpectedly in little cameo appearances. These underscore just how completely he dominated Europe in his brief but dramatic era of war and conquest, supreme glory and abject defeat. The next planned destination is the Italian island of Elba, the one place where we would expect to find sites intimately linked to Napoleon’s life. It was on Elba that he was forced into exile (along with about 1000 servants and troops as bodyguards) after a series of defeats in 1814.

The next planned destination is the Italian island of Elba, the one place where we would expect to find sites intimately linked to Napoleon’s life. It was on Elba that he was forced into exile (along with about 1000 servants and troops as bodyguards) after a series of defeats in 1814. Then we anchor off Viareggio, back on the Italian coast in Tuscany, and take a day trip inland to Florence. We have arranged a walking tour to enjoy the glorious and stunning medieval and Renaissance architecture, monumental public sculptures and inviting pedestrian-only piazzas. It is far too brief, of course, but our personal guide takes us to some special places, such as the studio of a blacksmith who creates fantastic birds, fishes and other creatures in steel, and to the guide’s own favourite and funky “Cafe of the Artisans.” We stroke the snout of an iconic bronze wild boar and share a kiss, thus assuring our return to Florence some day.

Then we anchor off Viareggio, back on the Italian coast in Tuscany, and take a day trip inland to Florence. We have arranged a walking tour to enjoy the glorious and stunning medieval and Renaissance architecture, monumental public sculptures and inviting pedestrian-only piazzas. It is far too brief, of course, but our personal guide takes us to some special places, such as the studio of a blacksmith who creates fantastic birds, fishes and other creatures in steel, and to the guide’s own favourite and funky “Cafe of the Artisans.” We stroke the snout of an iconic bronze wild boar and share a kiss, thus assuring our return to Florence some day. Farther north on the Italian Riviera, our ship anchors off the picturesque village of Portofino, with its brightly painted old houses. Once a simple fishing village, it now has an upscale yacht harbour catering to the rich and famous. Going ashore for a few hours, we hike up to a striking castle that dominates the small bay. And sure enough, Napoleon left his mark here as well during the years when France controlled northern Italy. What we see is an ancient fortification that Napoleon modernized, greatly expanded and equipped with better cannons. Not one for modesty, he renamed the village Port Napoleon.

Farther north on the Italian Riviera, our ship anchors off the picturesque village of Portofino, with its brightly painted old houses. Once a simple fishing village, it now has an upscale yacht harbour catering to the rich and famous. Going ashore for a few hours, we hike up to a striking castle that dominates the small bay. And sure enough, Napoleon left his mark here as well during the years when France controlled northern Italy. What we see is an ancient fortification that Napoleon modernized, greatly expanded and equipped with better cannons. Not one for modesty, he renamed the village Port Napoleon. While a student, I had bunked at a unique youth hostel in a little modern castle overlooking Finale Ligure, a lovely stretch of coastal villages on the Italian Riviera only an hour east of Monaco. We decide to return to explore those intriguing shores, with their rich and diverse history. It was here that the 15-year-old Margaret Theresa of Spain stopped briefly in 1666 while on her way to Vienna to marry Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor. A triumphal arch commemorating the event dominates the central piazza, not far from ancient fortifications that marked the long-fought-over boundary between Spanish and Genoese-controlled territories. A few miles east is the village of Varigotti with its strikingly Moorish houses. These were built in the ninth and tenth centuries by the Muslim Saracens, who ruled the area for nearly 100 years. Long thereafter, they remained both a threat and a trading partner to the region, bringing such goods as salt from Ibiza when Spain was still under Moorish rule.

While a student, I had bunked at a unique youth hostel in a little modern castle overlooking Finale Ligure, a lovely stretch of coastal villages on the Italian Riviera only an hour east of Monaco. We decide to return to explore those intriguing shores, with their rich and diverse history. It was here that the 15-year-old Margaret Theresa of Spain stopped briefly in 1666 while on her way to Vienna to marry Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor. A triumphal arch commemorating the event dominates the central piazza, not far from ancient fortifications that marked the long-fought-over boundary between Spanish and Genoese-controlled territories. A few miles east is the village of Varigotti with its strikingly Moorish houses. These were built in the ninth and tenth centuries by the Muslim Saracens, who ruled the area for nearly 100 years. Long thereafter, they remained both a threat and a trading partner to the region, bringing such goods as salt from Ibiza when Spain was still under Moorish rule.