Italy’s Fatal Gift of Beauty

by Sarah Humphreys

Italia! Oh Italia! Thou who hast the fatal gift of Beauty,”

Nowhere does Byron’s tribute to Italy ring more true than in “The Gulf of Poets” on the Ligurian coast, where Percy Bysshe Shelley was drowned in 1822. It is said that the spirit of the English Romantic poet still lives on between the inlets and promontories of this bewitching cove. It is easy to see why.

Stretching from Lerici to Portovenere, in a succession of beaches, jagged coastlines, crystalline waters and raw nature, the Gulf of La Spezia’s literary nickname derives from the attraction the area has had for writers, painters and artists, including Percy and Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, D. H Lawrence, George Sands, Henry Miller and Virginia Woolf.

Percy and Mary Shelley arrived in the tiny seaside village of San Terenzo in 1819 and rented a villa known as “Casa Magni”, whose whitewashed walls and arched colonnade can be found on the promenade. “A lonely house close by the soft and sublime scenes of the Bay of Lerici”, is how Shelley described the villa in his letters. These lines are inscribed on the walls of the now uninhabited villa, along with “I still inhabit this Divine Bay, reading dramas and sailing and listening to the most enchanting music.”

Percy and Mary Shelley arrived in the tiny seaside village of San Terenzo in 1819 and rented a villa known as “Casa Magni”, whose whitewashed walls and arched colonnade can be found on the promenade. “A lonely house close by the soft and sublime scenes of the Bay of Lerici”, is how Shelley described the villa in his letters. These lines are inscribed on the walls of the now uninhabited villa, along with “I still inhabit this Divine Bay, reading dramas and sailing and listening to the most enchanting music.”

The Shelleys were often visited by Lord Byron, who resided nearby in Portovenere, supposedly in a cave. Byron is said to have swum the incredible 7.5 kilometre distance just to visit his dear friends. Standing at the bottom of “Byron’s grotto” which bears a plaque commemorating “the immortal poet who as a daring swimmer defied the waves of the sea from Portovenere to Lerici.” staring out over the rocks which peer up from the sea, it would seem this story is rather far-fetched, although the romantic in me chooses to believe. As night falls, the grotto takes on an eerie atmosphere, rocks transform into monstrous figures and it is easy to see how the poets found their muse in this stirring landscape. Byron is believed to have written his poem “The Corsair” in the grotto itself.

A sprinkling of brightly coloured houses line medieval streets that wind up to Lerici’s castle, which overlooks the entrance to the Gulf of Poets. The castle is thought to be the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Nowadays the castle contains a museum of palaeontology.

A sprinkling of brightly coloured houses line medieval streets that wind up to Lerici’s castle, which overlooks the entrance to the Gulf of Poets. The castle is thought to be the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Nowadays the castle contains a museum of palaeontology.

Shelley composed some of his most beautiful lyrics and songs in this area including “Lines written in the Bay of Lerici” and was working on “The Triumph of Life” at the time of his tragic drowning. Sailing from Livorno to San Terenzo, his boat named “Don Juan” by Byron, but referred to as “Ariel” by the Shelleys, was sunk in a severe storm. The bodies of Shelley and his two English companions, Edward Ellerker Williams and Charles Vivien, were washed up on a beach near Viareggio and cremated in the presence of Byron, and friends Leigh Hunt and Edward Trelawny. A copy of Keats’ poems was found in Shelley’s jacket pocket. According to legend, Shelley’s heart refused to burn in the flames and the ever-audacious Byron plucked it from the embers.

Shelley’s’ ashes were stored in the wine cellar of The British Consul in Rome before being buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Rome, where John Keats was laid to rest just a year before. After Mary Shelley’s death, her husband’s heart was found wrapped in a page of “Adonais”, Shelley’s famous elegy to Keats. Shelley’s heart was eventually buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Bournemouth, Dorset.

Shelley’s’ ashes were stored in the wine cellar of The British Consul in Rome before being buried in The Protestant Cemetery in Rome, where John Keats was laid to rest just a year before. After Mary Shelley’s death, her husband’s heart was found wrapped in a page of “Adonais”, Shelley’s famous elegy to Keats. Shelley’s heart was eventually buried in St Peter’s Churchyard in Bournemouth, Dorset.

Walking along the coast from Lerici to San Terenzo, the incandescent extent of the waters, reflecting the pastel colours of the attractive buildings, bring to mind Mary Shelley’s words “O blessed shores, where Love, Liberty and Dreams have no chains.”

The best of Cinque Terre & Portovenere with Typical Ligurian Lunch

If You Go:

The nearest airports are Pisa and Florence.

♦ Lerici can be reached by ferry from La Spezia, Portovenere and The Cinque Terre. Ferries run from 1st April. There’s a scenic drive from La Spezia and there’s a large car park etween San Terenzo and Lerici. A shuttle bus runs between the two, but it is a short walk to either village.

♦ Portovenere can be reached by ferry from La Spezia or Lerici. There is a bus from the train station in La Spezia.

♦ The Gulf of Poets can get very crowded in high season. Best times to visit are Spring and Autumn.

For details on accommodation, restaurants and other travel information:

♦ www.portovenere.it

♦ www.rivieradellaliguria.com

Portovenere and Cinque Terre from Florence Private Custom Tour

About the author:

Sarah Humphreys has been writing since she could hold a pencil. She is originally from near Liverpool in the UK but she’s lived in The USA, Greece, The Czech Republic and Italy. She’s been living in Pistoia, near Florence for 15 years, where she teaches English. She is passionate about poetry, Literature, music and travel.

All photos are by Sarah Humphreys:

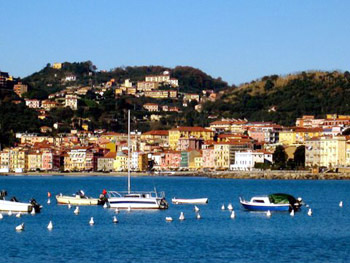

San Terenzo

Looking down over ‘Byron’s Grotto’ and the Castle at Portovenere

Sunset over the Gulf of Poets

Lerici harbour looking towards PortoVenere

The Vidroule River flows leisurely along its defined banks flanked by nurtured trees and a tended walkway. A pastoral setting so peaceful we were entertained by a solitary otter swimming slowly by, oblivious to the nearness of people and cars. Cafes colonize the walkway with tented outdoor seating offering customers a tree shaded view of the Vidroule and its famous bridge. In its time the bridge was the only crossing of the Vidroule between the Mediterranean and the Cevenne Mountains; hence Sommieres’ ancient importance.

The Vidroule River flows leisurely along its defined banks flanked by nurtured trees and a tended walkway. A pastoral setting so peaceful we were entertained by a solitary otter swimming slowly by, oblivious to the nearness of people and cars. Cafes colonize the walkway with tented outdoor seating offering customers a tree shaded view of the Vidroule and its famous bridge. In its time the bridge was the only crossing of the Vidroule between the Mediterranean and the Cevenne Mountains; hence Sommieres’ ancient importance.

Today the chateau, partially restored and turned to museum remembrances, recalls eras of siege and troubles. Initially constructed between the 10th and 11th centuries at its height it had two towers frowning over river and town of which but one remains. Its first mention in records was in 1041. As its prominence passed it was employed as a prison and eventually lapsed into partial private and public ownership. From its heights town and country spread out in a broad vista.

Today the chateau, partially restored and turned to museum remembrances, recalls eras of siege and troubles. Initially constructed between the 10th and 11th centuries at its height it had two towers frowning over river and town of which but one remains. Its first mention in records was in 1041. As its prominence passed it was employed as a prison and eventually lapsed into partial private and public ownership. From its heights town and country spread out in a broad vista. Sommieres, at 4,500 population, is not the prominent town it was those many years ago which makes it all the more inviting as it’s medieval heart continues to dominate and afford much for the wandering feet of visitors. Narrow streets and lanes sprout off in all directions yet maintain the Roman dominance of grid patterns. In some cases arches over streets have evolved into windowed buildings creating little tunnels to explore and, dotted throughout, are small arches spanning between buildings as some form of support. The narrowed confines open to readily framed vistas for telling photos.

Sommieres, at 4,500 population, is not the prominent town it was those many years ago which makes it all the more inviting as it’s medieval heart continues to dominate and afford much for the wandering feet of visitors. Narrow streets and lanes sprout off in all directions yet maintain the Roman dominance of grid patterns. In some cases arches over streets have evolved into windowed buildings creating little tunnels to explore and, dotted throughout, are small arches spanning between buildings as some form of support. The narrowed confines open to readily framed vistas for telling photos.

The bridge has also felt the steps of moved masses coming from Mozart’s premier of “Don Giovanni.” Perhaps the happy tempo of these steps felt similar to those that walked the bridge in 1918 when Czech people crossed it — citizens of a sovereign country for the first time in their long history.

The bridge has also felt the steps of moved masses coming from Mozart’s premier of “Don Giovanni.” Perhaps the happy tempo of these steps felt similar to those that walked the bridge in 1918 when Czech people crossed it — citizens of a sovereign country for the first time in their long history.

Then came The Devil. No one knows exactly when he first came, but everyone agrees it was over 10 years ago. On the edge of the bridge he set up shop where he thought he belonged, next to the other artists selling their creations to eager tourists in front of the Mala Strana tower.

Then came The Devil. No one knows exactly when he first came, but everyone agrees it was over 10 years ago. On the edge of the bridge he set up shop where he thought he belonged, next to the other artists selling their creations to eager tourists in front of the Mala Strana tower. Did he believe he was the devil? Why the Charles Bridge? Was it all a ploy for the money or was their some higher reason for what he did? I don’t know. And I won’t know. When I set out to find him and ask, he was not to be found. The other vendors informed me with long faces that he recently passed away.

Did he believe he was the devil? Why the Charles Bridge? Was it all a ploy for the money or was their some higher reason for what he did? I don’t know. And I won’t know. When I set out to find him and ask, he was not to be found. The other vendors informed me with long faces that he recently passed away.

It appeared that he was a real person, one Charles de Batz, who joined the Musketeers in 1632, using his mother’s maiden name, D’Artagnan. There, the resemblance ends, for Dumas fictionalised and romanticised his character heavily.

It appeared that he was a real person, one Charles de Batz, who joined the Musketeers in 1632, using his mother’s maiden name, D’Artagnan. There, the resemblance ends, for Dumas fictionalised and romanticised his character heavily. The reason for this is its important strategic position on the River Maas, where the Romans, in their progress across Europe, built a bridge, around which grew a town which they called Mosae Trajectum, or ‘Maas Crossing’, from which the name Maastricht is derived.

The reason for this is its important strategic position on the River Maas, where the Romans, in their progress across Europe, built a bridge, around which grew a town which they called Mosae Trajectum, or ‘Maas Crossing’, from which the name Maastricht is derived. But, the French came again; briefly during the War of Austrian Succession in 1748, and, for a longer time, by the forces of Napoleon in 1794, who regarded it as a part of France until its restoration to the Netherlands in 1815.

But, the French came again; briefly during the War of Austrian Succession in 1748, and, for a longer time, by the forces of Napoleon in 1794, who regarded it as a part of France until its restoration to the Netherlands in 1815. Perhaps it was this central position which led to its being chosen as the meeting place for Europe’s leaders in 1992. They discussed the mechanism by which the European Community became the European Union, and laid the groundwork for Europe’s common currency. At the end of their conference, they signed the Treaty of European Union, better known as the Maastricht Treaty.

Perhaps it was this central position which led to its being chosen as the meeting place for Europe’s leaders in 1992. They discussed the mechanism by which the European Community became the European Union, and laid the groundwork for Europe’s common currency. At the end of their conference, they signed the Treaty of European Union, better known as the Maastricht Treaty.

In 1418 Henry the Navigator became Governor of the Algarve, although at the time he was only plain Prince Henry. He founded a School of Navigation in the town of Sagres, which helped to put Portugal on the map in terms of seafaring and plotting long voyages on the ocean waves. Sadly the school was destroyed by the army of Sir Francis Drake in 1587. Henry the Navigator’s other achievements were to discover new territories in Cape Verde, Madeira, Sierra Leone and the Azores.

In 1418 Henry the Navigator became Governor of the Algarve, although at the time he was only plain Prince Henry. He founded a School of Navigation in the town of Sagres, which helped to put Portugal on the map in terms of seafaring and plotting long voyages on the ocean waves. Sadly the school was destroyed by the army of Sir Francis Drake in 1587. Henry the Navigator’s other achievements were to discover new territories in Cape Verde, Madeira, Sierra Leone and the Azores.