Yucatan, Mexico

by Emese Fromm

As I was standing on top of the Acropolis, the tallest building in Ek Balam, my first thought was “I stood on top of this when it was just a pile of rocks, covered with vegetation”. I didn’t realize that I said it out loud, and a few of my fellow visitors stopped to ask me about it. I normally don’t like to be the center of attention, but I really enjoyed talking about my older adventures at the same site, when it was just rubble.

I had visited Ek Balam for the first time in 1995. I was on the way to Chichen Itza from Coba, on the old road. After passing the town of Valladolid, a dirt road led to this small site. It was called Ek Balam, Night Jaguar. I ended up there about midday when it was hot and humid, with no breeze at all. However, after driving all morning on a dirt road that seemed to be in the middle of nowhere and leading to nowhere, I spotted a small palapa hut. It was the ticket booth, and it looked deserted, just like everything else around us. When I stopped, an old Mayan man came out to the front of the hut. He was the caretaker of the site, or the ticket agent. I wished that I could speak Mayan, and his Spanish wasn’t much better than mine, so I felt like it was a missed opportunity to get to know someone interesting and to learn more about the place I was visiting from a local. I purchased my ticket from him and he pointed me in the right direction and I set off to see this little-known site.

I had visited Ek Balam for the first time in 1995. I was on the way to Chichen Itza from Coba, on the old road. After passing the town of Valladolid, a dirt road led to this small site. It was called Ek Balam, Night Jaguar. I ended up there about midday when it was hot and humid, with no breeze at all. However, after driving all morning on a dirt road that seemed to be in the middle of nowhere and leading to nowhere, I spotted a small palapa hut. It was the ticket booth, and it looked deserted, just like everything else around us. When I stopped, an old Mayan man came out to the front of the hut. He was the caretaker of the site, or the ticket agent. I wished that I could speak Mayan, and his Spanish wasn’t much better than mine, so I felt like it was a missed opportunity to get to know someone interesting and to learn more about the place I was visiting from a local. I purchased my ticket from him and he pointed me in the right direction and I set off to see this little-known site.

The site was barely excavated, and totally deserted. Alone with the ancient ruins, I felt like a true explorer. Fortunately there were quite a few trees, so most of the walk was shaded, but the heat and humidity was making me feel very sluggish, even with the excitement of being in a deserted ancient city.

As I got used to walking in clothes dripping with sweat, I started feeling better, especially when I spotted the few structures that were standing. Most of the buildings were overgrown with vegetation, and some were just piles of rubble. I climbed on every mound and knew that I was walking or standing on a pyramid, or another ancient building.

I realized that the tallest pile of rubble, overgrown with trees, was a good sized pyramid. Although steep, with a barely visible trail on it, I climbed to its top. It was a real challenge for me since there were not even tall enough trees growing on it to shade me from the scorching sun. In spite of it, I still made it to the top and was rewarded with a great view. I could only guess how important this site would have been with a structure this big. I fantasized on seeing the pyramid and its features, wondering what they were like. I noticed big pieces of cut stones, that I recognized as part of a building. As I learned in later years, I had been standing on top of the Acropolis, indeed the biggest structure at the site.

I realized that the tallest pile of rubble, overgrown with trees, was a good sized pyramid. Although steep, with a barely visible trail on it, I climbed to its top. It was a real challenge for me since there were not even tall enough trees growing on it to shade me from the scorching sun. In spite of it, I still made it to the top and was rewarded with a great view. I could only guess how important this site would have been with a structure this big. I fantasized on seeing the pyramid and its features, wondering what they were like. I noticed big pieces of cut stones, that I recognized as part of a building. As I learned in later years, I had been standing on top of the Acropolis, indeed the biggest structure at the site.

After getting off that mound, I kept walking through the small site. I noticed a pile of rectangular stones, cleaned and gleaming in the bright sun. Most of the stones were numbered, like pieces of a puzzle. It was such an exciting discovery for me, a sign of the work of archeologists. I knew now that they were in the process of reconstructing the site, or at least some of the buildings. I also knew that I would return to see it excavated and rebuilt.

Revisiting the Site

Years later, there I was standing on top of the same tall mound, but this time I had climbed it on a stairway, stopping along the way to marvel at the statues on its sides. The view from the top was pretty much the same though there were a lot more structures standing.

Years later, there I was standing on top of the same tall mound, but this time I had climbed it on a stairway, stopping along the way to marvel at the statues on its sides. The view from the top was pretty much the same though there were a lot more structures standing.

I was definitely not alone at the site this time, and it had a different feel with all the buildings standing and a multitude of people around me. I enjoyed seeing the buildings in their entirety. The fact that I had seen them overgrown and deserted before made it so much more magical for me.

Ek Balam is a very compact site. Although it was a larger city, only the center of it, the main plaza has been excavated, which covers about one square mile. This makes it very easy to walk, though. A large arch stands at the entrance of the city, with the remains of a sac-be going through it. The sac-be, or ancient Mayan road (translated as “white road”, due to the color of the limestone that it had been constructed from), connected Ek Balam to other sites, like Coba and Chichen Itza. When I passed through the arch, I felt like I had entered the ancient city.

Ek Balam is a very compact site. Although it was a larger city, only the center of it, the main plaza has been excavated, which covers about one square mile. This makes it very easy to walk, though. A large arch stands at the entrance of the city, with the remains of a sac-be going through it. The sac-be, or ancient Mayan road (translated as “white road”, due to the color of the limestone that it had been constructed from), connected Ek Balam to other sites, like Coba and Chichen Itza. When I passed through the arch, I felt like I had entered the ancient city.

On the way to the main pyramid, I walked through the Ball Court, similar in size to the ones in Coba. I tried to imagine the ancient ones playing the ball game and how high they had to get the ball to make it through the hoops.

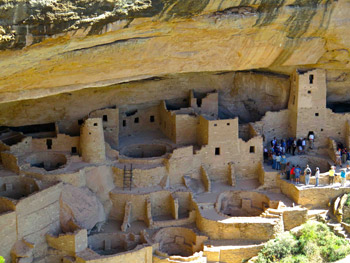

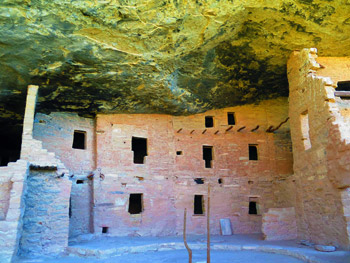

The Acropolis is definitely one of the most impressive structure in all of the Yucatan, a palace and pyramid in one. Though not as tall as Nohuch Mul in Coba, it is much larger overall, measuring 480 ft in length, 180 ft in width and 96 ft in height. Since it has been excavated, it is definitely the most spectacular, with all of the intricately carved figures, unlike any other we’ve seen in all of Yucatan, standing on its walls. The palace has six levels, and at the entrance a monster-like figure, possibly a jaguar, with huge carved teeth is guarding the entrance to the Underworld, the place the Ancient Maya went after death.

The Acropolis is definitely one of the most impressive structure in all of the Yucatan, a palace and pyramid in one. Though not as tall as Nohuch Mul in Coba, it is much larger overall, measuring 480 ft in length, 180 ft in width and 96 ft in height. Since it has been excavated, it is definitely the most spectacular, with all of the intricately carved figures, unlike any other we’ve seen in all of Yucatan, standing on its walls. The palace has six levels, and at the entrance a monster-like figure, possibly a jaguar, with huge carved teeth is guarding the entrance to the Underworld, the place the Ancient Maya went after death.

Inside the pyramid is the tomb of a great ruler, Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’. Other than the jaguar, many other carved figures, some of the warriors, decorate the walls.

After finally leaving this amazing structure I went to the other set of buildings walked around then climbed all three palaces, overlooking an impressive courtyard. While exploring all of these structures, I came across many round holes in the ground, or on the structures, the inside of which were all carefully paved with rocks. These are Mayan chultuns, used to collect rainwater.

Writing in Stone

There is no Mayan site without at least one stelae, a large standing stone, filled with drawing and writing, and Ek Balam is no exception. The one here depicts a ruler, with the hieroglyphic writing around his figure, erected in honor of Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’. Writing in stone was very important to the Maya. They have erected stelae in every known site. It was a way for them to record history and preserve their past. They have also written codices or books, however, most of those didn’t survive, burned by the Spaniards or just disappeared in the jungle, so stelae are very important for the study the Mayan writing and history. They were usually erected to commemorate a moment in history, a moment important to someone, mostly to the rulers of the cities. Because of this, stelae have a figure of the ruler they are talking about, with the important dates in his life. They have the date of his birth, of his accession as a ruler, some important dates of his rule, and finally the date of his death or descend into the Underworld.

There is no Mayan site without at least one stelae, a large standing stone, filled with drawing and writing, and Ek Balam is no exception. The one here depicts a ruler, with the hieroglyphic writing around his figure, erected in honor of Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’. Writing in stone was very important to the Maya. They have erected stelae in every known site. It was a way for them to record history and preserve their past. They have also written codices or books, however, most of those didn’t survive, burned by the Spaniards or just disappeared in the jungle, so stelae are very important for the study the Mayan writing and history. They were usually erected to commemorate a moment in history, a moment important to someone, mostly to the rulers of the cities. Because of this, stelae have a figure of the ruler they are talking about, with the important dates in his life. They have the date of his birth, of his accession as a ruler, some important dates of his rule, and finally the date of his death or descend into the Underworld.

Before leaving, I took a last look at the Acropolis and thought back to the day when I had first seen it, and how I had imagined what a great pyramid lay under all that rubble. Now it is visible to the public, and it is spectacular.

If You Go:

Ek Balam [TOP PHOTO], a Mayan site meaning “Black Jaguar”, is situated between two major sites, Coba and Chichen Itza. It is easy to get to at this time since it is part of the Mayan Riviera. The road is paved, and wide, with lights on it as well. It is a side road off the main one between Cancun and Valladolid, with signs for Ek Balam. The site is about 20 miles from the colonial town of Valladolid. There is a small town by the ruins, with a restaurant and hotel. Another attraction at the ruins is a cenote, Xcan-Che, open to the public, and worth the stop.

The ancient city was occupied for about one thousand years, from the Late Pre-Classic (100 B.C. – 300 A.D.) to the Late Classic (700 – 900 A.D.) period of the Mayan civilization. There is evidence that the site was founded by its first ruler, Coch Cal Balam, around 100 B.C. It was at its strongest and most populated around the Late Classic period, between 700 – 1000 A.D., when most of its structured have been built. At its peak, around 800 A.D, its ruler was Ukit Kan Le’k Tok’, whose tomb had been found inside the Acropolis. As excavations are still ongoing, there is not much more known about this site, except that the architecture is different from the nearby sites though they have been occupied around the same time.

Private Tour: Ek Balam, Chichen Itza and Cenote from Cancun

About the author:

Emese Fromm is a writer and translator, fascinated by Ancient Mayan Ruins. She has been visiting them with her husband for over 20 years while also learning about the people who built them. They have taken their children on these visits since they believe that traveling is the best education for them.

All photos by Jeff Fromm:

Ek Balam

On top of the Acropolis

On top of the Acropolis

View from the top of the Acropolis

The Acropolis – The Ball Court

Large jaguar teeth guard the entrance to the underworld

Carved figures on the Acropolis

The Spa is part of the resort and offers a tranquil setting for spa treatments and a large outdoor swimming pool that even in the Spring season was warm enough to enjoy. The spa treatment was a highlight of my stay there, a great way to relax after a long journey or a busy week in the city. If you make physical fitness part of your day, the resort has an excellent fully equipped Fitness Centre ringed by an indoor running track.

The Spa is part of the resort and offers a tranquil setting for spa treatments and a large outdoor swimming pool that even in the Spring season was warm enough to enjoy. The spa treatment was a highlight of my stay there, a great way to relax after a long journey or a busy week in the city. If you make physical fitness part of your day, the resort has an excellent fully equipped Fitness Centre ringed by an indoor running track. There are many things to enjoy at Semiahmoo and in the Watcom Country area. If you’re a golfer you can enjoy a day on the two golf courses at the Semiahomoo Gold & Country Club. The resort is surrounded by nature so whether it’s a walk on the beach or on a forest trail, exploring the historic outlying buildings, a picnic at Peace Arch State Park or an afternoon of gambling at a nearby casino, there is something for everyone to enjoy. Boat cruises are available as well as whale watching, sea kayaking, scuba diving or fishing. We enjoyed wandering around the resort area exploring the old boat sheds and waterfront area where they have signs posted with bits of local history or of ecological interest.

There are many things to enjoy at Semiahmoo and in the Watcom Country area. If you’re a golfer you can enjoy a day on the two golf courses at the Semiahomoo Gold & Country Club. The resort is surrounded by nature so whether it’s a walk on the beach or on a forest trail, exploring the historic outlying buildings, a picnic at Peace Arch State Park or an afternoon of gambling at a nearby casino, there is something for everyone to enjoy. Boat cruises are available as well as whale watching, sea kayaking, scuba diving or fishing. We enjoyed wandering around the resort area exploring the old boat sheds and waterfront area where they have signs posted with bits of local history or of ecological interest. Several miles south, located just a few minutes east of the 1-5 exit 201, an hour north of Seattle, is the newly refurbished Angel of the Winds Casino Hotel in Arlington. It is owned by the Stillaguamish Tribe which has operated the casino since 2004 on their lands. The new hotel just opened in December 2014 and has 125 guestrooms as well as gift shops, dining and entertainment.

Several miles south, located just a few minutes east of the 1-5 exit 201, an hour north of Seattle, is the newly refurbished Angel of the Winds Casino Hotel in Arlington. It is owned by the Stillaguamish Tribe which has operated the casino since 2004 on their lands. The new hotel just opened in December 2014 and has 125 guestrooms as well as gift shops, dining and entertainment.

Our first stop for the morning was Tulip Town The landmark windmill was built by owner Tom de Goede, a replica of his family’s windmill in Holland. We enjoyed an hour of browsing among the gorgeous varieties of tulips still blooming In the vast fields as well as displayed in the beautifully decorated gallery where there are landscape murals depicting various scenes in Holland . We were greeted by the owner’s wife, Jeanette Boudreau, who happens to be originally from French Canada. She explained the various species of tulips and told us about the operation of the farm. There is entertainment for children at Tulip Town too, with face painting and a kite flying display every weekend.

Our first stop for the morning was Tulip Town The landmark windmill was built by owner Tom de Goede, a replica of his family’s windmill in Holland. We enjoyed an hour of browsing among the gorgeous varieties of tulips still blooming In the vast fields as well as displayed in the beautifully decorated gallery where there are landscape murals depicting various scenes in Holland . We were greeted by the owner’s wife, Jeanette Boudreau, who happens to be originally from French Canada. She explained the various species of tulips and told us about the operation of the farm. There is entertainment for children at Tulip Town too, with face painting and a kite flying display every weekend. Next on the road trip was RoozenGaarde, another lovely tulip farm near Mount Vernon Wa. Where the flower fields were still blooming. I was especially impressed by the wide yellow fields of daffodils. There were flower beds and a picturesque park area to browse through. The founder, William Roozen emigrated from Holland in 2947 and started a bulb farm on five acres of land which has now grown to be the largest tulip-bulb grower In the country. Roozen Gaarde was established in 1985 by the Roozen family (the name means ‘rose’) and is an official sponsor of the Skagit Valley Tulip Festival.

Next on the road trip was RoozenGaarde, another lovely tulip farm near Mount Vernon Wa. Where the flower fields were still blooming. I was especially impressed by the wide yellow fields of daffodils. There were flower beds and a picturesque park area to browse through. The founder, William Roozen emigrated from Holland in 2947 and started a bulb farm on five acres of land which has now grown to be the largest tulip-bulb grower In the country. Roozen Gaarde was established in 1985 by the Roozen family (the name means ‘rose’) and is an official sponsor of the Skagit Valley Tulip Festival.

He explained that Horton House was one of the oldest standing tabby structures in the state of Georgia. When I looked at him strangely, he laughed again.

He explained that Horton House was one of the oldest standing tabby structures in the state of Georgia. When I looked at him strangely, he laughed again. When I told him I was interested in hearing more, he continued: “They’d pour it into large forms that had been made with two parallel planks of wood These would measure the length of the structure’s outer walls. When each tabby mixture had set, the boards would be moved upwards repeatedly, until the desired height of the home was reached. If you really love history, you don’t want to miss this piece of it!”

When I told him I was interested in hearing more, he continued: “They’d pour it into large forms that had been made with two parallel planks of wood These would measure the length of the structure’s outer walls. When each tabby mixture had set, the boards would be moved upwards repeatedly, until the desired height of the home was reached. If you really love history, you don’t want to miss this piece of it!” The moment I caught sight of the ruins of Horton House, I stopped short. With its scarred openings for windows and wide-open doorways, this deserted house echoed with the drama of its last inhabitants. Its two-story structure stood proudly beneath the overhanging beauty of gigantic tree branches. I jumped off the bike and parked it nearby.

The moment I caught sight of the ruins of Horton House, I stopped short. With its scarred openings for windows and wide-open doorways, this deserted house echoed with the drama of its last inhabitants. Its two-story structure stood proudly beneath the overhanging beauty of gigantic tree branches. I jumped off the bike and parked it nearby. The house was built by Major William Horton, second in command, serving under General James Oglethorpe and in charge of troops that were entrenched further North, on St. Simon’s Island. Horton House is surrounded by rich land, which was perfect for harvesting cotton and indigo, as well as hops and barley. Horton actually produced Georgia’s first beer and supplied ale to the troops and settlers at nearby Ft Frederica. I wondered what a cold glass of that had tasted like, way back when!

The house was built by Major William Horton, second in command, serving under General James Oglethorpe and in charge of troops that were entrenched further North, on St. Simon’s Island. Horton House is surrounded by rich land, which was perfect for harvesting cotton and indigo, as well as hops and barley. Horton actually produced Georgia’s first beer and supplied ale to the troops and settlers at nearby Ft Frederica. I wondered what a cold glass of that had tasted like, way back when! One of the land grant conditions stated that Horton would have to bring 10 indentured servants with him from England, one for each fifty acres of land. He was also required to have 20% of the land cultivated and sustainable, within the first ten years of his settling in Georgia.

One of the land grant conditions stated that Horton would have to bring 10 indentured servants with him from England, one for each fifty acres of land. He was also required to have 20% of the land cultivated and sustainable, within the first ten years of his settling in Georgia.

In 1791, four Frenchmen from Sapelo Island jointly purchased Jekyll Island. Later, one of them, Poulain du Bignon, became the sole owner. As a young officer, Poulain served in the French Army in India, fighting against Great Britain. Later, he commanded a French Naval vessel. He moved into Horton House in1792, several years after the American Revolution. Bignon died in 1825. He was eighty-six. He’s buried with other members of his family, across the street from Horton House, with a peaceful view of Bignon Creek. A single oak tree marks his passing.

In 1791, four Frenchmen from Sapelo Island jointly purchased Jekyll Island. Later, one of them, Poulain du Bignon, became the sole owner. As a young officer, Poulain served in the French Army in India, fighting against Great Britain. Later, he commanded a French Naval vessel. He moved into Horton House in1792, several years after the American Revolution. Bignon died in 1825. He was eighty-six. He’s buried with other members of his family, across the street from Horton House, with a peaceful view of Bignon Creek. A single oak tree marks his passing. The remaining Bignon family continued to own Jekyll Island, working together to manage the plantation and it’s crops. Eventually they decided to sell the property to a group of millionaires in 1886. They, in turn, promptly formed The Jekyll Island Club, a playground for the rich and famous. Many of the world’s wealthiest families became members in it’s heyday. Most notably were the Morgan, Vanderbilt and Rockefeller empires.Today, the Jekyll Island Club is a luxury resort and a member of the Historic Hotels Of America.

The remaining Bignon family continued to own Jekyll Island, working together to manage the plantation and it’s crops. Eventually they decided to sell the property to a group of millionaires in 1886. They, in turn, promptly formed The Jekyll Island Club, a playground for the rich and famous. Many of the world’s wealthiest families became members in it’s heyday. Most notably were the Morgan, Vanderbilt and Rockefeller empires.Today, the Jekyll Island Club is a luxury resort and a member of the Historic Hotels Of America.

Pfeiffer had a penchant for fighting in the nude, or so it would seem. His first nude encounter happened on June 20, 1863, as a forty-one year-old captain based at Fort McRae, near today’s Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. (The fort has since been flooded by Elephant Butte Reservoir). The captain had taken ill and thought the hot springs, about six miles from the fort near the Rio Grande River, would be beneficial for his malady. He bathed in the curative springs, while his pregnant wife of seven years, Antonita, his adopted daughter Maria, and her attendant Mrs. Mercardo, bathed in a pool nearby. His three-year old son Albert had been left at the fort with servants. Additionally, soldiers accompanied the group to safeguard their bathing at El Ojo del Muerto, the Spring of the Dead.

Pfeiffer had a penchant for fighting in the nude, or so it would seem. His first nude encounter happened on June 20, 1863, as a forty-one year-old captain based at Fort McRae, near today’s Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. (The fort has since been flooded by Elephant Butte Reservoir). The captain had taken ill and thought the hot springs, about six miles from the fort near the Rio Grande River, would be beneficial for his malady. He bathed in the curative springs, while his pregnant wife of seven years, Antonita, his adopted daughter Maria, and her attendant Mrs. Mercardo, bathed in a pool nearby. His three-year old son Albert had been left at the fort with servants. Additionally, soldiers accompanied the group to safeguard their bathing at El Ojo del Muerto, the Spring of the Dead. Pfeiffer’s only thoughts were to save his wife and daughter. With his rifle lying close by, he instinctively leapt for the rifle, running to the safety of the nearby river bank, completely nude. Clothes were the least of his concern. According to the November 1933 issue of The Colorado Magazine, “He was followed by the Indians who shot at him, one of the arrows entering his back with the end coming out in front. In this condition, with the arrow in his back, he ran until he reached an enclosure of rock where he made a halt to rest and defend himself.” Later, he arrived at the fort with an embedded arrow just below his heart, more dead than alive. Still naked, Pfeiffer was barely recognizable as his sunburned skin peeled off in layers. “When the surgeon drew out the arrow from his back, the sun-scorched skin surrounding the wound came off with it, and for days the Captain suffered intense agony and lay for two months at the point of death,” according to the magazine.

Pfeiffer’s only thoughts were to save his wife and daughter. With his rifle lying close by, he instinctively leapt for the rifle, running to the safety of the nearby river bank, completely nude. Clothes were the least of his concern. According to the November 1933 issue of The Colorado Magazine, “He was followed by the Indians who shot at him, one of the arrows entering his back with the end coming out in front. In this condition, with the arrow in his back, he ran until he reached an enclosure of rock where he made a halt to rest and defend himself.” Later, he arrived at the fort with an embedded arrow just below his heart, more dead than alive. Still naked, Pfeiffer was barely recognizable as his sunburned skin peeled off in layers. “When the surgeon drew out the arrow from his back, the sun-scorched skin surrounding the wound came off with it, and for days the Captain suffered intense agony and lay for two months at the point of death,” according to the magazine.

Pfeiffer was so despondent over the loss of his family that he vowed to kill Apaches to avenge their death. It almost became a passion. The Colorado Chieftain newspaper on June 29, 1871, read: “It was a bad day for the Apaches when they killed old Pfeiffer’s family. He made several trips, alone, into their country, staying, sometimes for months, and always seemed pleased, for a few days, on his return. He was always accompanied by about half a dozen wolves in the Apache country. ‘They like me,’ he said once, ‘because they’re fond of dead Indian, and I feed them well.'”

Pfeiffer was so despondent over the loss of his family that he vowed to kill Apaches to avenge their death. It almost became a passion. The Colorado Chieftain newspaper on June 29, 1871, read: “It was a bad day for the Apaches when they killed old Pfeiffer’s family. He made several trips, alone, into their country, staying, sometimes for months, and always seemed pleased, for a few days, on his return. He was always accompanied by about half a dozen wolves in the Apache country. ‘They like me,’ he said once, ‘because they’re fond of dead Indian, and I feed them well.'” The Utes and the Navajos both revered the healing powers of the hot springs, located at modern-day Pagosa Springs, in southwestern, Colorado. The Utes had laid claim to the land generations prior to the Navajo challenge, but shared the springs because of their sacred origins. Then, in late 1866, the Navajo challenged the Utes for control of the springs, fighting for several days to stake their claim. Unfortunately, it ended in a stalemate.

The Utes and the Navajos both revered the healing powers of the hot springs, located at modern-day Pagosa Springs, in southwestern, Colorado. The Utes had laid claim to the land generations prior to the Navajo challenge, but shared the springs because of their sacred origins. Then, in late 1866, the Navajo challenged the Utes for control of the springs, fighting for several days to stake their claim. Unfortunately, it ended in a stalemate.

Evidence of settlement on the Colorado Plateau only dates back to AD 550, but signs of human presence on the plateau go back at least 10,000 years to the Paleolithic Age. For much of the known history of these people, they existed as tribes of wandering hunter gathers. Forging for food is easier than farming.

Evidence of settlement on the Colorado Plateau only dates back to AD 550, but signs of human presence on the plateau go back at least 10,000 years to the Paleolithic Age. For much of the known history of these people, they existed as tribes of wandering hunter gathers. Forging for food is easier than farming. The Anasazi are rich in history. What is emerging is from the archeology work is a complex and, somewhat egalitarian, society. They succeeded to thrive for millennium in a sparse land with harsh winters. The archeological evidence of the Anasazi date back to 1200 BC—a time known as the “Basket Making Era” since they had baskets, but no pottery, and lived in camps or caves, surviving off a staple of cultivated squash and corn.

The Anasazi are rich in history. What is emerging is from the archeology work is a complex and, somewhat egalitarian, society. They succeeded to thrive for millennium in a sparse land with harsh winters. The archeological evidence of the Anasazi date back to 1200 BC—a time known as the “Basket Making Era” since they had baskets, but no pottery, and lived in camps or caves, surviving off a staple of cultivated squash and corn.

If you’re coming from Denver, you’ll enjoy the scenic, mountain-carved route along US Highway 160W and US 285S. I drove in from Grand Junction, along US 50. If you can do this drive in the fall, roll your windows down and you can smell the yellow and red leaves bursting in bright patches amongst ever-steady green pines. Carved cliffs of rock will add earthy tones to the pallet, and blue sky might cause you to turn the radio down so as to let the evolving panoramic fill your senses.

If you’re coming from Denver, you’ll enjoy the scenic, mountain-carved route along US Highway 160W and US 285S. I drove in from Grand Junction, along US 50. If you can do this drive in the fall, roll your windows down and you can smell the yellow and red leaves bursting in bright patches amongst ever-steady green pines. Carved cliffs of rock will add earthy tones to the pallet, and blue sky might cause you to turn the radio down so as to let the evolving panoramic fill your senses.