by Jason Templer

Doe-eyed and powder-faced, the girls march in single file through a wooden hula-hoop, flourishing their Muromachi-style kimonos as camera shots fill the air like a multitudinous flutter of pigeons. Sitting down to perform the rice dance, Reiko peers back at the throng of camera-toting tourists in a wizened look of innocence, as if disapproving the vain Instagram and twitter paparazzos.

Doe-eyed and powder-faced, the girls march in single file through a wooden hula-hoop, flourishing their Muromachi-style kimonos as camera shots fill the air like a multitudinous flutter of pigeons. Sitting down to perform the rice dance, Reiko peers back at the throng of camera-toting tourists in a wizened look of innocence, as if disapproving the vain Instagram and twitter paparazzos.

Waving straw fans, a kin-blooded group of elders appraise the ceremony with austere silence. The Osaka sun painting yellow splotches on their meditative frown lines. Bandana-headed boys pound the Taiko drums as the first group of flat-hatted girls bow deeply in a circle before Sumiyoshi shrine. Then with the syncopated rhythm of drums and woodblock strikes, they dip down into the earth with invisible plows, performing the first moves of the Sumiyoshi harvest festival dance.

It can be challenging to find active celebrants of cultural heritage in a country brimming with high-tech electro gadgets, cars, and robots – a tech junkie’s utopia. But as policemen wielding mini light sabers herd me into the siphoned viewing areas of one of Japan’s summer throwback festivals, my hopes of witnessing authentic local traditions are realized.

Donning a Spiderman hat from Osaka’s Universal Studios, I crop out the outstretched forearms of iPhones and cameras to capture photos of the anachronistic dance.

The warbling hum of seated monks on the backstage of Sumiyoshi shrine’s cypress wood floors leaves me oddly enchanted. The ceremony makes me think of old school teachers haranguing students on correct behavior; but the kids aren’t coaxed by singing lectures nor monkish divinity, they continue skipping and clapping as if never returning from playground recess.

The Shinto priests croon their incantations like a chorus of exotic birds, some of the monks whistling through bamboo flutes that give off the airy overtone of meditating in a peaceful temple garden. Wearing oversized green night gowns, thin ballooned pants, and black pouch hats, I imagine the monks are like divine parakeets, flying to the heavens in inflatable pajamas, and singing their prayers to Sumiyoshi Sanjin – one of the three deities of Shinto religion in Japan. In the dusty foreground of the shrine, the paddle-clapping girls chant and clap like playing a game of ring-around-the rosy tethered to an imaginary maypole, and keeping in perfect rhythm with the drummer boys.

No doubt the melodious effect of this quirky ensemble is blessing for a propitious harvest, one marked by youthful vitality and elderly wisdom.

Peace-fingering me in a yellow-flowered kimono, I meet Reiko as one of the dance performers, a high-school student from the Kansai area of Japan. “It’s fun to dance in summer with friends and family.” She says, fanning a plastic-Mickey Mouse fan over the runnels of sweat trickling down her powder-caked face.

Peace-fingering me in a yellow-flowered kimono, I meet Reiko as one of the dance performers, a high-school student from the Kansai area of Japan. “It’s fun to dance in summer with friends and family.” She says, fanning a plastic-Mickey Mouse fan over the runnels of sweat trickling down her powder-caked face.

We eat kakigori (shaved ice) in a teeming plaza of Vendors and tourists near Sumiyoshi shrine. Reiko goes on to tell me the folk legend of the harvest dance tradition, known as dengaku. Reputedly, empress Jungu, a Japanese empress from the early 3rd century AD, prepared for an invasion of Korea. The legendary queen, born from parents with mouthful-pronouncing names (Okinaganosukunenomiko and Kazurakinotakanukahime) dispatched young female rice planters to Sumiyoshi shrine to plant rice – thus to covet her war campaign as an auspicious event with divine favor. After receiving seeds from the main temple sanctuary, they walk to a sacred field. The seeds cultivated on this holy soil are given to farmers so that when the seeds sprout, the crops are harvested as magical grains of rice, believed to have power from Sumiyoshi Sanjin.

Warned by an oracle, the empress instructed the temple’s architect named Tamomi no Sukune, to enshrine the Shinto god before eventually immortalizing herself there.

Touted as one of the greatest summer festivals in Osaka city, Sumiyoshi festival is held over four days and congregates at the Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine or (Sumiyoshi Taisha). The Shinto temple garners an ancient reputation for being one of the oldest in Japan, only third to the Ise and Izumo shrines.

As a signature of its popularity, the temple brandishes a roofed hip-knob or okichigi, a samurai-crossed wooden centerpiece over five horizontal billets of timber. Without using a plethora of gaudy religious ornaments, the use of woodwork evokes a certain warrior attitude and simplistic charm – an aesthetic background for spiritual warriors like Empress jingu to meet and receive blessings for future battles.

Worshipped as the headquarters for 2,000 of Japan’s Sumiyoshi shrines, Sumiyoshi Taisha enshrines Sumiyoshi Sanjin as not only a god of harvest, but a protector of land, sea, and patron of waka, a Japanese style of poetry that implements 31 syllables in comparison to haiku’s truncated 17 syllable form. Holding her hand to hide her mirth, Reiko fails to suppress a schoolgirl giggle. “At some Sumiyoshi temples men bathe in the rice water.” According to folklore myth, a crane dropped the first seed, which sprouted as a rice-deity at Izu shrine. To honor this humble beginning, naked men climb down into the flooded farm field and jump and splash like skinny-dipping in a giant mud bath.

Ostensibly, the purpose isn’t just to create a full-monty like spectacle but to divine answers from a symbolic deity; a giant pole standing in the field, representing Sumiyoshi Sanjin, falls down at a certain side of the rice field (maybe due to the pool’s build-up of testosterone or from an all-together masculine pull) which answers fortune-telling questions for local villagers.

Ostensibly, the purpose isn’t just to create a full-monty like spectacle but to divine answers from a symbolic deity; a giant pole standing in the field, representing Sumiyoshi Sanjin, falls down at a certain side of the rice field (maybe due to the pool’s build-up of testosterone or from an all-together masculine pull) which answers fortune-telling questions for local villagers.

After a monk’s closing speech, the performers march back in procession through the city streets. “Walking through the Chinowa (a ring of straw) is good luck” says Reiko. “I want to do well on tests and go to a good university.”

She notes that the festival starts with a purification shower on Umi no hi (Sea Day July 3rd) and climaxes around the end of July known as Nagoshi Harai Shinji, where starry-eyed fortune-seekers not only duck their heads through for good luck, but to purify oneself of negative energies.

If You Go:

You can travel to the Otaue rice harvest festival on June 14th in Osaka. Please visit www.jnto.go.jp/eng/spot/festival/otauericeplanting.html

You can also attend the summer matsuri festival on Marine Day in Japan (July 16th or the third Monday of July) and from July 30th to August 1st.

The festival location is about 3 minute walk from Sumiyoshi Taisha Station on the Nankai Dentetsu line coming from Shin-Imamiya station. Or you can get off at Sumiyoshihigashi Station by taking the Nankai Koya line on the Nankai Electric Railway in Osaka city.

About the author:

Jason is an aspiring free-lance writer who has pitched his tent abroad in Czech Republic, Korea, and Japan, empowering youth and consulting foreign businesses and governments on English language skills and professional development. In his spare time, he finds time to write, energizing his synapses with quirky travel memoirs and budget-roughing misadventures, believing his endless vagabonding is on a fruitful quest for authenticity.

Image credits:

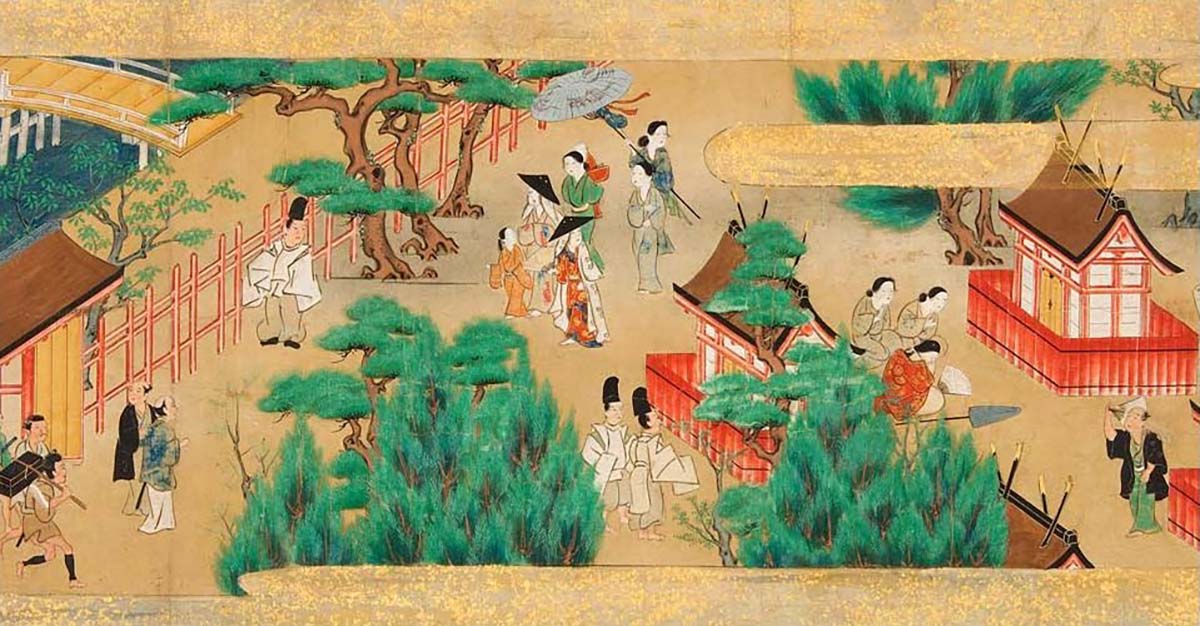

17th Century Festival at Sumiyoshi Shrine (detail), Japan, Edo period, 17th century, anonymous handscroll, ink, color and gold on paper, Honolulu Museum of Art by Unknown author / Public domain

All photos by Jason Templer, jasonw4770@yahoo.com

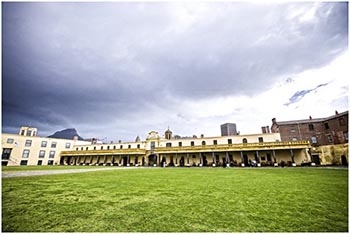

Not only a destination for the history buffs, Castle of Good Hope is a top historical site to explore when visiting Cape Town. This is the oldest surviving building in South Africa and after its restoration in the ‘80s it is considered one of the best preserved examples of DEIC (Dutch East India Company) architecture in the world. Not only the Castle of Good Hope provides an insight on the country’s colonial past, it also hosts numerous art and photography exhibitions for the tourists and locals, being an active cultural site.

Not only a destination for the history buffs, Castle of Good Hope is a top historical site to explore when visiting Cape Town. This is the oldest surviving building in South Africa and after its restoration in the ‘80s it is considered one of the best preserved examples of DEIC (Dutch East India Company) architecture in the world. Not only the Castle of Good Hope provides an insight on the country’s colonial past, it also hosts numerous art and photography exhibitions for the tourists and locals, being an active cultural site.

This impressive historic building has been the seat of the National Parliament since 1910 and it opens its gates for tourists each year when the Parliament is in session (first part of the year). Be sure to book a visit in advance if you’re traveling from another country and get informed about any closed doors events. You can admire over 4,000 artworks collected by the gallery of the House of Parliament and enjoy a walk around the premises. The guided tours are free of charge and you can also book tours for groups of up to 25 people.

This impressive historic building has been the seat of the National Parliament since 1910 and it opens its gates for tourists each year when the Parliament is in session (first part of the year). Be sure to book a visit in advance if you’re traveling from another country and get informed about any closed doors events. You can admire over 4,000 artworks collected by the gallery of the House of Parliament and enjoy a walk around the premises. The guided tours are free of charge and you can also book tours for groups of up to 25 people.

We were staying in a riad, and this one turned out to be a destination in itself. A “riad” is a traditional Moroccan house, located within the ancient medina and designed around a central courtyard, pool or fountain, and garden. The owners had purchased several adjoining houses and combined them so that there are two courtyards and 26 guest rooms, several sitting rooms, two restaurants, a jazz bar, and a spa. The hotelier gave us a tour and showed us to a lovely room which faced the pool and inner courtyard. As I stood on the balcony, I looked out over rooftops of the old city and a minaret a short distance away. Down below was a pool, trees, potted plants, tables covered with white tablecloths, pierced pendant lanterns, and lovely tile work. Each morning at dawn, we were awakened to the “call to prayer” from the mosque. A traditional afternoon tea is offered in the courtyard each day, and we enjoyed typically Moroccan mint tea served with an assortment of tiny cookies. It felt like something out of “Arabian Nights”.

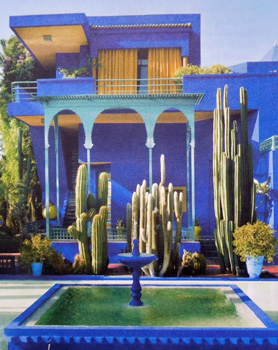

We were staying in a riad, and this one turned out to be a destination in itself. A “riad” is a traditional Moroccan house, located within the ancient medina and designed around a central courtyard, pool or fountain, and garden. The owners had purchased several adjoining houses and combined them so that there are two courtyards and 26 guest rooms, several sitting rooms, two restaurants, a jazz bar, and a spa. The hotelier gave us a tour and showed us to a lovely room which faced the pool and inner courtyard. As I stood on the balcony, I looked out over rooftops of the old city and a minaret a short distance away. Down below was a pool, trees, potted plants, tables covered with white tablecloths, pierced pendant lanterns, and lovely tile work. Each morning at dawn, we were awakened to the “call to prayer” from the mosque. A traditional afternoon tea is offered in the courtyard each day, and we enjoyed typically Moroccan mint tea served with an assortment of tiny cookies. It felt like something out of “Arabian Nights”. Within walking distance of the riad is the Majorelle Garden, a botanical and landscape garden that was created in the 1920’s by French painter Jacques Majorelle. It is a fantastical delight and beautiful to behold. Special shades of bold cobalt blue are used in the gardens and on the buildings, walkways and pergolas, and are a stunning accent to the greens of the cacti, palm trees, bamboo, bougainvilleas, and ferns. Neglected after the painter’s death in 1962, the property was later restored by fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent who bought the garden and used it as his residence. After he died in 2008, his ashes were scattered in the garden and a memorial was built in his honor.

Within walking distance of the riad is the Majorelle Garden, a botanical and landscape garden that was created in the 1920’s by French painter Jacques Majorelle. It is a fantastical delight and beautiful to behold. Special shades of bold cobalt blue are used in the gardens and on the buildings, walkways and pergolas, and are a stunning accent to the greens of the cacti, palm trees, bamboo, bougainvilleas, and ferns. Neglected after the painter’s death in 1962, the property was later restored by fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent who bought the garden and used it as his residence. After he died in 2008, his ashes were scattered in the garden and a memorial was built in his honor.

The “souk” is the commercial quarter of the medina and we went there to experience the activity and to bargain for some souvenirs. Colorful stalls line the alleyways, selling everything from carpets to clothing, scarves, jewelry, leather products, olives and housewares. We were on a quest to find a decorative tagine like the ones used on our riad’s breakfast buffet for fruits, nuts and pastries. Mohammed patiently took us from stall to stall until my sister finally found one to bring back home with her. There are no set prices in the souk so she had to use her bargaining skills. It can get rather tense as the seller dramatically tells the buyer that she is “killing” him with the low price she is offering. But in the end, she prevailed and took home a beautiful tagine to use for entertaining in the Moroccan style.

The “souk” is the commercial quarter of the medina and we went there to experience the activity and to bargain for some souvenirs. Colorful stalls line the alleyways, selling everything from carpets to clothing, scarves, jewelry, leather products, olives and housewares. We were on a quest to find a decorative tagine like the ones used on our riad’s breakfast buffet for fruits, nuts and pastries. Mohammed patiently took us from stall to stall until my sister finally found one to bring back home with her. There are no set prices in the souk so she had to use her bargaining skills. It can get rather tense as the seller dramatically tells the buyer that she is “killing” him with the low price she is offering. But in the end, she prevailed and took home a beautiful tagine to use for entertaining in the Moroccan style. There also was an interesting specialty shop in the souk where three Berber women were laboriously extracting oil from the nuts of the argan tree to make food products and cosmetics. Argan trees are endemic to Morocco and the oil that is extracted is very precious and has many health benefits. A salesman let us sample some of their special products, and we filled our baskets with gifts for people back home. There was no bargaining here because supposedly this is the only place where the skin products are pure and the oils used for cooking are not diluted.

There also was an interesting specialty shop in the souk where three Berber women were laboriously extracting oil from the nuts of the argan tree to make food products and cosmetics. Argan trees are endemic to Morocco and the oil that is extracted is very precious and has many health benefits. A salesman let us sample some of their special products, and we filled our baskets with gifts for people back home. There was no bargaining here because supposedly this is the only place where the skin products are pure and the oils used for cooking are not diluted. The Koutoubia Mosque with its 254 foot high minaret is a landmark and symbol of the city. We were just outside the mosque when the “call to prayer” came from the loudspeakers above. Not far away is the Bahia Palace, a masterpiece of Moroccan architecture with its brilliant mosaics, carved woodwork and gorgeous marbles. Like most Arab palaces, it contains charming and tranquil gardens, beautiful patios and rooms richly decorated with tiles. And we visited the tombs of the Saâdi rulers which date back to the 16th century but were only discovered and restored around 1917. These tombs shelter the bodies of about 60 Saadian sultans and their families and are an outstanding example of Moorish tilework and art.

The Koutoubia Mosque with its 254 foot high minaret is a landmark and symbol of the city. We were just outside the mosque when the “call to prayer” came from the loudspeakers above. Not far away is the Bahia Palace, a masterpiece of Moroccan architecture with its brilliant mosaics, carved woodwork and gorgeous marbles. Like most Arab palaces, it contains charming and tranquil gardens, beautiful patios and rooms richly decorated with tiles. And we visited the tombs of the Saâdi rulers which date back to the 16th century but were only discovered and restored around 1917. These tombs shelter the bodies of about 60 Saadian sultans and their families and are an outstanding example of Moorish tilework and art.

Ouarzazate, nicknamed “the door of the (Sahara) Desert”, was built as a garrison and administrative center by the French, but today it serves as the Hollywood of the Kingdom. This is where “Lawrence of Arabia”, “Jesus of Nazareth”, “Gladiator”, “Indiana Jones” and many other films were made. While it is in a lovely setting, the town itself is somewhat tacky. There are several movie studios that you can tour and new housing developments are springing up in the otherwise beautiful landscape.

Ouarzazate, nicknamed “the door of the (Sahara) Desert”, was built as a garrison and administrative center by the French, but today it serves as the Hollywood of the Kingdom. This is where “Lawrence of Arabia”, “Jesus of Nazareth”, “Gladiator”, “Indiana Jones” and many other films were made. While it is in a lovely setting, the town itself is somewhat tacky. There are several movie studios that you can tour and new housing developments are springing up in the otherwise beautiful landscape. Leaving casbah Ait Benhaddou, we drove for miles through the foothills of the mountains and the rolling sand hills of the desert and started to wonder where we could possibly be staying for the night. Hopefully not in a Bedouin tent! But when we finally came upon our riad, we drove through a large sandstone arch and entered a typical Moroccan courtyard, set in an oasis with palm trees and beautiful plantings around a central pool and fountain. You’d never expect to find a place like this here in such a remote location. But it does make sense—a Frenchman opened it to cater to the movie industry.

Leaving casbah Ait Benhaddou, we drove for miles through the foothills of the mountains and the rolling sand hills of the desert and started to wonder where we could possibly be staying for the night. Hopefully not in a Bedouin tent! But when we finally came upon our riad, we drove through a large sandstone arch and entered a typical Moroccan courtyard, set in an oasis with palm trees and beautiful plantings around a central pool and fountain. You’d never expect to find a place like this here in such a remote location. But it does make sense—a Frenchman opened it to cater to the movie industry.

As you fly into Johannesburg you would expect to see the wild game from the runway. Close to the tarmac is a beautiful view of elephant grass (tall grasses) and native trees that bring memories of photos depicting Africa or the Lion King. I travelled there in August which would be the southern hemisphere winter. Well, if that is winter, it sure does not resemble the Canadian winters. Each day, whether in Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban, or Capetown all provided an average temperature between 26 to 29C each day and sunshine over my three week adventure. South Africa winter certainly is quite manageable.

As you fly into Johannesburg you would expect to see the wild game from the runway. Close to the tarmac is a beautiful view of elephant grass (tall grasses) and native trees that bring memories of photos depicting Africa or the Lion King. I travelled there in August which would be the southern hemisphere winter. Well, if that is winter, it sure does not resemble the Canadian winters. Each day, whether in Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban, or Capetown all provided an average temperature between 26 to 29C each day and sunshine over my three week adventure. South Africa winter certainly is quite manageable.

My first experience in SA was a 1.5 hr drive to Sun City. If you have watched the movie Blended you will have seen one of the hotels as the movie was filmed at Sun City Palace and the complex. There are four hotels on the premises ranging up to $8000 per night. Something for everyone, Players golf course, a children’s arcade, spa, casino, and high tea at 3 pm is highly recommended to see the Sun Palace hotel as that is the only access to this posh hotel.

My first experience in SA was a 1.5 hr drive to Sun City. If you have watched the movie Blended you will have seen one of the hotels as the movie was filmed at Sun City Palace and the complex. There are four hotels on the premises ranging up to $8000 per night. Something for everyone, Players golf course, a children’s arcade, spa, casino, and high tea at 3 pm is highly recommended to see the Sun Palace hotel as that is the only access to this posh hotel. Food is also a bargain either at the grocery store or at the restaurants. Kentucky Fried Chicken appeared to be the most popular fast food to be found in SA with Macdonald’s a close second. KFC signage is atop the illuminated street names and almost on every street corner similar to Starbucks can be found in Canada. Both KFC and MacDonald’s offer free scooter delivery service for orders. Other restaurants offer bountiful breakfasts that can be found for around $3. Restaurants are also inexpensive offering lunch specials ranging from R57 ($5.70 CDN) which includes a salad and portions that are monstrous. Bottles of wine can start at R110 and up in a restaurant and beer at R25. Evening dinner options can be a full chicken and salad for R90. That would be a feast for a big appetite or a feast and a take home feast for the lighter appetites. Don’t worry if you don’t finish that bottle of wine. You can take it home. Most places appear to be children friendly with play areas and some even have child attendants. Some restaurants offer a complete experience for children to order their own pizza and help the chef make their pizza. Children put on their own toppings while the parents can enjoy a leisurely lunch or dinner.

Food is also a bargain either at the grocery store or at the restaurants. Kentucky Fried Chicken appeared to be the most popular fast food to be found in SA with Macdonald’s a close second. KFC signage is atop the illuminated street names and almost on every street corner similar to Starbucks can be found in Canada. Both KFC and MacDonald’s offer free scooter delivery service for orders. Other restaurants offer bountiful breakfasts that can be found for around $3. Restaurants are also inexpensive offering lunch specials ranging from R57 ($5.70 CDN) which includes a salad and portions that are monstrous. Bottles of wine can start at R110 and up in a restaurant and beer at R25. Evening dinner options can be a full chicken and salad for R90. That would be a feast for a big appetite or a feast and a take home feast for the lighter appetites. Don’t worry if you don’t finish that bottle of wine. You can take it home. Most places appear to be children friendly with play areas and some even have child attendants. Some restaurants offer a complete experience for children to order their own pizza and help the chef make their pizza. Children put on their own toppings while the parents can enjoy a leisurely lunch or dinner. Driving is an experience. Although sidewalks are a rare finding, the large dirt sections next to the road offer opportunities for vendors to set up business and cars can pull off the road to shop; SA people are very enterprising. On most traffic lighted city street corners, men can be found wandering between the lanes selling most anything: Newspapers, toys, pens, crafts, computer gadgets, but I did not see a kitchen sink. Companies and businesses also hire people to advertise at the street light corners to hand out pamphlets. It is always recommended, no matter where you may be in the world, to travel and drive with your doors locked. As anywhere, there are places that you should not venture for safety reasons. Having said that, I did not experience any adverse experiences. In SA taxi services are communal for the locals. Specific hand gestures indicate where you want to travel as the taxi vans travel the streets. People are packed 4 across and 5 deep holding over 20 people per taxi van.

Driving is an experience. Although sidewalks are a rare finding, the large dirt sections next to the road offer opportunities for vendors to set up business and cars can pull off the road to shop; SA people are very enterprising. On most traffic lighted city street corners, men can be found wandering between the lanes selling most anything: Newspapers, toys, pens, crafts, computer gadgets, but I did not see a kitchen sink. Companies and businesses also hire people to advertise at the street light corners to hand out pamphlets. It is always recommended, no matter where you may be in the world, to travel and drive with your doors locked. As anywhere, there are places that you should not venture for safety reasons. Having said that, I did not experience any adverse experiences. In SA taxi services are communal for the locals. Specific hand gestures indicate where you want to travel as the taxi vans travel the streets. People are packed 4 across and 5 deep holding over 20 people per taxi van.

Mabalingwe was my first experience in a wild game reserve. This is under two hours from Pretoria. Your first view of a kudu, impala or warthog is exhilarating and you can’t get your camera poised fast enough. After a while the appetite for photographing new wild game gets more and more intriguing. The first 24 hours I had sited and photographed 14 different wild African animals in their natural environment. This included the ostrich, impala, kudu, baboon, warthog, bandit mongoose, giraffe, zebra, hippopotamus, crocodile, hyrax, duiker, hyala, and jackal. Patience is a virtue and wild animals do not pose or come out from behind the brushes. They do, however, need water and that is a good place to see many different animals. The best time of the day to find animals is the early morning and closer to the end of the day. Even in winter, midday is too warm for the animals and they siesta until closer to the end of day. Our morning safari were as early as 6 am and the sunset safari started at 3 pm as it becomes dark around 6 pm.

Mabalingwe was my first experience in a wild game reserve. This is under two hours from Pretoria. Your first view of a kudu, impala or warthog is exhilarating and you can’t get your camera poised fast enough. After a while the appetite for photographing new wild game gets more and more intriguing. The first 24 hours I had sited and photographed 14 different wild African animals in their natural environment. This included the ostrich, impala, kudu, baboon, warthog, bandit mongoose, giraffe, zebra, hippopotamus, crocodile, hyrax, duiker, hyala, and jackal. Patience is a virtue and wild animals do not pose or come out from behind the brushes. They do, however, need water and that is a good place to see many different animals. The best time of the day to find animals is the early morning and closer to the end of the day. Even in winter, midday is too warm for the animals and they siesta until closer to the end of day. Our morning safari were as early as 6 am and the sunset safari started at 3 pm as it becomes dark around 6 pm.

“Balak!”

“Balak!” We amble down Talaa Kebira, one of the medina’s principal roadways, and soon come to Bou Inania Medersa. This is the most awe-inspiring Koranic school in Fes, and one of the few open to the public. Every room has lofty, sumptuously detailed ceilings with carved cedar beams and stunning onyx marble floors. The walls are covered with handcrafted tiles adorned with dazzling gold and turquoise geometric motifs. Intricate lime-coloured geometrical designs are also on display in the courtyard, where the 14th Century fountain still gushes today. In a corner an imam, a priest, kneels and chants verses from the Koran.

We amble down Talaa Kebira, one of the medina’s principal roadways, and soon come to Bou Inania Medersa. This is the most awe-inspiring Koranic school in Fes, and one of the few open to the public. Every room has lofty, sumptuously detailed ceilings with carved cedar beams and stunning onyx marble floors. The walls are covered with handcrafted tiles adorned with dazzling gold and turquoise geometric motifs. Intricate lime-coloured geometrical designs are also on display in the courtyard, where the 14th Century fountain still gushes today. In a corner an imam, a priest, kneels and chants verses from the Koran.

As we descend further into the bowels of the medina, our guide urges us to stay close together. She doesn’t have to tell me twice. I would love nothing better than to wander the zigzag of avenues on my own, but finding my way out would be nothing short of a miracle. I’m told that even the best maps are unreliable. The streets are swarming with humanity today; the thrum of voices is omnipresent. Since none of the roads are wide enough for cars to navigate, donkey carts and scooters are the accepted modes of transport, making this the world’s largest urban car-free zone.

As we descend further into the bowels of the medina, our guide urges us to stay close together. She doesn’t have to tell me twice. I would love nothing better than to wander the zigzag of avenues on my own, but finding my way out would be nothing short of a miracle. I’m told that even the best maps are unreliable. The streets are swarming with humanity today; the thrum of voices is omnipresent. Since none of the roads are wide enough for cars to navigate, donkey carts and scooters are the accepted modes of transport, making this the world’s largest urban car-free zone. From the Souk Attarine our odyssey continues. Blind alleys that seem to lead nowhere open onto swarming fundouks with gurgling fountains. We pass countless vendors that hawk candles, wood carvings, jewelry, and fresh herbs from shops hardly bigger than a closet. A posse of young boys plays a boisterous game of soccer with two rocks serving as goalposts. The frenetic energy of it all is exhilarating.

From the Souk Attarine our odyssey continues. Blind alleys that seem to lead nowhere open onto swarming fundouks with gurgling fountains. We pass countless vendors that hawk candles, wood carvings, jewelry, and fresh herbs from shops hardly bigger than a closet. A posse of young boys plays a boisterous game of soccer with two rocks serving as goalposts. The frenetic energy of it all is exhilarating.

There is one last stop on our schedule, and we don’t need a map to find it. The rank stench of the open air leather tanneries serves as a guidepost to one of Fes’ most famous attractions. We’re led up a staircase to a leather shop that opens onto a terrace where we view the tanneries below.

There is one last stop on our schedule, and we don’t need a map to find it. The rank stench of the open air leather tanneries serves as a guidepost to one of Fes’ most famous attractions. We’re led up a staircase to a leather shop that opens onto a terrace where we view the tanneries below. We’re seated on plush cushions around hand-carved wooden hexagon-shaped tables. The high ceiling is covered in gorgeous inlaid wood painted in shades of emerald, burgundy, and cobalt. It feels like we’re dining in someone’s home, and with good reason. A couple of years ago owners Fouad and Karima turned their sitting room and courtyard into a restaurant. They don’t have a liquor license, but they have no objections when we bring out cheap bottles of Moroccan wine that we bought at the supermarket.

We’re seated on plush cushions around hand-carved wooden hexagon-shaped tables. The high ceiling is covered in gorgeous inlaid wood painted in shades of emerald, burgundy, and cobalt. It feels like we’re dining in someone’s home, and with good reason. A couple of years ago owners Fouad and Karima turned their sitting room and courtyard into a restaurant. They don’t have a liquor license, but they have no objections when we bring out cheap bottles of Moroccan wine that we bought at the supermarket.