Africa

by Ian Packham

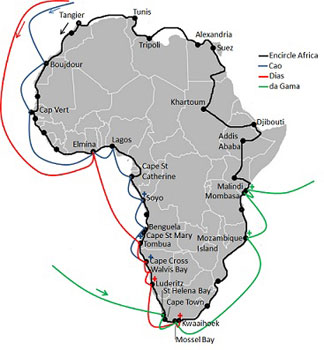

I was on the Kenyan coast at Malindi, having followed the African coast west from Tangier, Morocco’s seedy port of entrance for so many Europeans. I was attempting to complete the first solo and unsupported overland circumnavigation of the continent by public transport, an expedition I had christened Encircle Africa. But all the while, through eight months of travel from Tangier to Malindi, I was aware others had been there before me. Vasco da Gama reached Malindi in Kenya after nine months in 1498. He was on his way to the Malabar Coast of India. I was on my way back to Tangier, through East Africa and across the Mediterranean coast. For much of his route he followed passages determined by the earlier explorers Diogo Cao and Bartolomeu Dias. But while Dias returned home to a feeling of failure, da Gama returned a hero, celebrated like the Apollo 11 astronauts on their return from the moon.

The three Portuguese explorers I would continually cross paths with may have been the most visible, having positioned padrãos (navigational pillars) around three-quarters of the African continent, but they certainly weren’t the first. It is believed the Phoenicians made it so far, in the sixth century BC, as to be able to provide the first known description of the gorilla. Chinese ships rounded Cape Point from the east in 1421, decades before the Portuguese would do the same from the west. And Kenya’s coastal civilizations had been in contact with other continents for centuries. But it was Europe’s Portuguese explorers that opened up the continent for all that was to come, including my own personal exploration.

The padrãos had several intentions, as did the voyages around the African continent themselves. Portugal, surrounded by hostile kingdoms, turned to the sea to find a new route to India’s spice trade that eliminated greedy middle men. The padrãos not only acted as navigational aids, but proclaimed the land around them as Christian, and belonging to the Kingdom of Portugal. They were also a handy source of ballast, generally only positioned on a voyage’s homeward journey. The carved inscription on the Cape Cross padrão reads: “In the year…1485 after the birth of Christ, the most excellent and serene king Dom John II of Portugal ordered this land to be discovered and this padrão to be placed by Diogo Cao”.Namibia’s Cape Cross was Cao’s journeys end. The next 15 years would see countrymen Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama forge a sea route to India’s Malabar Coast. Each explorer was dependent upon the discoveries of those who had gone before and the padrãos they had positioned.

The padrãos had several intentions, as did the voyages around the African continent themselves. Portugal, surrounded by hostile kingdoms, turned to the sea to find a new route to India’s spice trade that eliminated greedy middle men. The padrãos not only acted as navigational aids, but proclaimed the land around them as Christian, and belonging to the Kingdom of Portugal. They were also a handy source of ballast, generally only positioned on a voyage’s homeward journey. The carved inscription on the Cape Cross padrão reads: “In the year…1485 after the birth of Christ, the most excellent and serene king Dom John II of Portugal ordered this land to be discovered and this padrão to be placed by Diogo Cao”.Namibia’s Cape Cross was Cao’s journeys end. The next 15 years would see countrymen Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama forge a sea route to India’s Malabar Coast. Each explorer was dependent upon the discoveries of those who had gone before and the padrãos they had positioned.

My first chance to cross paths with these explorers came after only two weeks, in Western Sahara, at the town of Boujdour. I missed any chance of even a glimpse of the town Cao had visited, since my only way south from Laayoune was a direct overnight coach to Dakhla. It would become a theme of Encircle Africa. Our paths didn’t cross again until Cap Vert, Senegal, the most westerly point of the African mainland.

Cao was able to sail straight to Elmina, Ghana from anchor at Cap Vert. I had had to struggle through the ever improving but often muddy dirt roads of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia just after the rains.

I didn’t get close enough to feel their influence until reaching Soyo on Angola’s northern border, the southern bank of the River Congo, four months after beginning. It took Cao about the same length of time by sail. Even then I was unable to find the fragmentary remains of his padrão which are said to exist.

I didn’t get close enough to feel their influence until reaching Soyo on Angola’s northern border, the southern bank of the River Congo, four months after beginning. It took Cao about the same length of time by sail. Even then I was unable to find the fragmentary remains of his padrão which are said to exist.

Cao and Dias made several different forays into Angola, with Cao stopping at Benguela and Cape Santa Maria, and Dias further south at Tombua. Yet the closest I came to the explorers in Angola was Diogo Cao Road in the heart of colonial Benguela. I reached the end of Cao’s expeditionary advances without getting any closer to them.

I relaxed knowing that for 500 years people like me had in some way or other been following the African coast. Whether it was Boujdour in Western Sahara or Benguela in Angola, people with far less knowledge of their environment had returned home. Those explorers used tiny ships called caravels. I didn’t have my own transport, but I had maps which the explorers didn’t, and a cell phone. We were both dependent on the locals to provide food and water.

Dias used Cao’s discoveries to continue, taking anchor 75 miles further south at Walvis Bay, a town still dependent on ships anchoring today. On its outskirts, monumental stylized rigged ships celebrate the town’s earlier European visitor.

Dias used Cao’s discoveries to continue, taking anchor 75 miles further south at Walvis Bay, a town still dependent on ships anchoring today. On its outskirts, monumental stylized rigged ships celebrate the town’s earlier European visitor.

Dias and his crew became the first Europeans to round the southern Capes. A beach at Cape Point, facing south towards Antarctica celebrates this fact, being named Dias beach. It’s a beautiful, blustery, cold place even now. For me it marked six months of travel, and Encircle Africa’s halfway point. Dias was reaching his end.

He landed at Mossel Bay to take on fresh water, on February 3 1488. The town is home to a replica caravel inside the Dias Museum. Dias was eager to continue his voyage, but his crew was not. His three caravels ended their outward journey at Kwaaihoek on March 14.

It was perhaps Dias of the three explorers that knew Africa best. Ten years on, Vasco Da Gama didn’t make landfall on the African continent until Saint Helena Bay, now a northern suburb of Cape Town, where a simple granite monument to his achievement can be seen.

From Mossel Bay da Gama faced unknown seas, passing Dias’ endpoint on December 16 1497. It was coming up to Christmas, so the coast da Gama spotted on his left hand side was named Natal (birth). His four caravels continued up the East coast of Africa eventually reaching Mozambique Island. Here on the island’s eastern end, facing a small, later Portuguese fort, I encountered the remains of his padrão. This was the closest I had come so far to one of the original navigational aids.

From Mossel Bay da Gama faced unknown seas, passing Dias’ endpoint on December 16 1497. It was coming up to Christmas, so the coast da Gama spotted on his left hand side was named Natal (birth). His four caravels continued up the East coast of Africa eventually reaching Mozambique Island. Here on the island’s eastern end, facing a small, later Portuguese fort, I encountered the remains of his padrão. This was the closest I had come so far to one of the original navigational aids.

Da Gama went on to reach Mombasa in Kenya, a town hostile to his intentions that forced him further north to Malindi. There, after much searching, I found a tourist office hidden around the back of an ugly building complex. I tentatively asked, knowing my success in locating signs of the explorers so far has not been great, if they knew about the padrão placed in the town by da Gama. There were baffled looks as the three staff members conversed. “You mean the pillar?” one of them suggested.

My search for the Portuguese explorers was finally over. I took a three-wheeled tuktuk to the padrão. The intervening years between me and da Gama had not been kind to it. Instead of the slim column of Lisbon limestone, it had been variously altered so it now resembled a giant white traffic cone topped with a Greek cross. Yet there it still stands on a rocky outcrop. One of the only original Portuguese padrãos I had been able to find during my own exploration of Africa 500 years on. From here da Gama went across the ocean to India. His mission complete, he returned home to report his successes to the king of Portugal. I still had to cross to Egypt, and follow the Mediterranean back to Tangier to Encircle Africa.

My search for the Portuguese explorers was finally over. I took a three-wheeled tuktuk to the padrão. The intervening years between me and da Gama had not been kind to it. Instead of the slim column of Lisbon limestone, it had been variously altered so it now resembled a giant white traffic cone topped with a Greek cross. Yet there it still stands on a rocky outcrop. One of the only original Portuguese padrãos I had been able to find during my own exploration of Africa 500 years on. From here da Gama went across the ocean to India. His mission complete, he returned home to report his successes to the king of Portugal. I still had to cross to Egypt, and follow the Mediterranean back to Tangier to Encircle Africa.

Mombasa Full-Day Guided City Tour

If You Go:

♦ See the map for details of the original sites of padrãos. A padrão from Cao’s explorations can now be viewed at the museum of the Lisbon Geographical Society, Portugal. The Cape Cross padrão is housed in the Deutsches Historisches Museum (Zeughaus), Berlin, Germany. Dias’ Kwaaihoek padrão de Sao Gregorio is to be found in the library foyer of the University of Witwatersand, Johannesburg, South Africa. These padrãos have been replaced by replicas at their original sites.

♦ The Dias Museum, Mossel Bay, South Africa also houses an aquarium, shell museum, Dias statue and the post office tree dating back to 1501. The museum complex is open daily except Christmas Day and Good Friday. There is an additional cost to enter the replica caravel inside the museum.

♦ The closest International airports to Malindi, Kenya are located in Nairobi and Mombasa. Several airlines provide flights from European and North American cities. Kenya Airways (a division of KLM) is the national carrier. Malindi is easily reachable by road from both cities.

Overnight Shark Cage Diving Excursion for Small Groups in Mossel Bay

About the author:

Ian is a biomedical scientist turned traveler. He is very much a ‘normal guy’ with no specialist expedition training. Encircle Africa was his first expedition. A member of the Royal Geographical Society, London, he enjoys off-beat off-season travel, preferably by public transport. He is still in the process of writing scientific articles, as well as fiction and non-fiction pieces. He aims to build on his current travels to develop a career in writing. Website: www.encircleafrica.org

All photographs copyright Ian M. Packham:

Map of my Encircle Africa route, and the routes of Cao (his second voyage), Dias and da Gama, depicting padrão sites.

Pointe des Almides, Cap Vert, Senegal. The most westerly point of continental Africa.

Dias entered Walvis Bay, Namibia on December 8 1487. A monument on the outskirts of the town marks his visit.

Cape Point, South Africa. Dias was the first European to round Africa’s southern capes.

The remains of da Gama’s padrão, Mozambique Island, Mozambique.

Da Gama’s padrão, Malindi, Kenya.

The present city with its much admired walls and Medina is a creation, a purpose built sea port, commissioned by King Mohammed III during the 18th century. He wanted to develop trade with Europe and beyond and to establish a counterbalance to Agadir, whose inhabitants favored a rival of him. For twelve years, the king instructed and oversaw French engineer and architect Theodore Cornut, who designed the modern city, the medina and the international quarters. At the time, Morocco depended heavily on the caravan trade, which brought merchandise from sub-Saharan Africa to Timbuktu, then from there through the desert and over the Atlas mountains to Marrakesh and, finally, making use of the straight road, to the thriving port of Essaouira.

The present city with its much admired walls and Medina is a creation, a purpose built sea port, commissioned by King Mohammed III during the 18th century. He wanted to develop trade with Europe and beyond and to establish a counterbalance to Agadir, whose inhabitants favored a rival of him. For twelve years, the king instructed and oversaw French engineer and architect Theodore Cornut, who designed the modern city, the medina and the international quarters. At the time, Morocco depended heavily on the caravan trade, which brought merchandise from sub-Saharan Africa to Timbuktu, then from there through the desert and over the Atlas mountains to Marrakesh and, finally, making use of the straight road, to the thriving port of Essaouira.

The long stretched island of Mogador protects Essaouira from the strongest Atlantic winds, but there is still plenty around to make the place a paradise for surfers and kite surfers. The wide, white beaches invite to sunbathing, swimming and any other imaginable kind of water sport.

The long stretched island of Mogador protects Essaouira from the strongest Atlantic winds, but there is still plenty around to make the place a paradise for surfers and kite surfers. The wide, white beaches invite to sunbathing, swimming and any other imaginable kind of water sport.

Small wonder that this picturesque, sedate and slightly melancholic city attracted such divers personalities as Churchill, Welles and Hendrix. Orson Welles even got honored with a statue, although his nose is now missing.

Small wonder that this picturesque, sedate and slightly melancholic city attracted such divers personalities as Churchill, Welles and Hendrix. Orson Welles even got honored with a statue, although his nose is now missing.

We were the only guests at Residence LaPasoa, as we would be elsewhere. There’s nothing quite like the threat of cyclones and a coup d’etat to keep the tourists away. After the coup, the journalists poked their noses into the pub, Ku De Ta, just for the name. It was all quite wonderful for us, but not for those gentle people who lived from tourism. But there was little to be nervous about. Life goes on; people go about their business because that’s what they have to do.

We were the only guests at Residence LaPasoa, as we would be elsewhere. There’s nothing quite like the threat of cyclones and a coup d’etat to keep the tourists away. After the coup, the journalists poked their noses into the pub, Ku De Ta, just for the name. It was all quite wonderful for us, but not for those gentle people who lived from tourism. But there was little to be nervous about. Life goes on; people go about their business because that’s what they have to do.

We had the dogs of La Crique with us, three of them, led by a little mutt who was a terror for chickens. With the emergence of a lanky Malagasy chicken from the rice or bush his ears perked and in two seconds the chase was on. The other dogs followed. They killed a chicken on that walk. I felt like I’d stolen from somebody. They weren’t even our dogs.

We had the dogs of La Crique with us, three of them, led by a little mutt who was a terror for chickens. With the emergence of a lanky Malagasy chicken from the rice or bush his ears perked and in two seconds the chase was on. The other dogs followed. They killed a chicken on that walk. I felt like I’d stolen from somebody. They weren’t even our dogs. You get to the tiny island of Ille aux Nattes by pirogue, though you can walk the channel. The boatmen line up and beseech you to vote for their boat. We stayed at Baboo Village, next to a place owned by a South African, Ockie. He too had only two guests, Dutch with some business on Madagascar. They were aimlessly chilling with Ockie, watching DVDs on the widescreen in the evening and in the mornings sitting on the deck with coffee and whiskey watching the pirogues cross the channel with their cargo.

You get to the tiny island of Ille aux Nattes by pirogue, though you can walk the channel. The boatmen line up and beseech you to vote for their boat. We stayed at Baboo Village, next to a place owned by a South African, Ockie. He too had only two guests, Dutch with some business on Madagascar. They were aimlessly chilling with Ockie, watching DVDs on the widescreen in the evening and in the mornings sitting on the deck with coffee and whiskey watching the pirogues cross the channel with their cargo.

Durban throbs with the rhythms of Black Africa that are not as accessible on the typical tourist track. The aromas wafting from stalls and cafés are unidentifiable, but worth exploring. Street vendors sell everything from beadwork to biltong (spicy, dried meat). The African taxis, actually ten-passenger vans, clog the city streets hawking for business and owning the road. Women carry grocery bags on their heads and kids on their backs. It’s high energy here and crowded.

Durban throbs with the rhythms of Black Africa that are not as accessible on the typical tourist track. The aromas wafting from stalls and cafés are unidentifiable, but worth exploring. Street vendors sell everything from beadwork to biltong (spicy, dried meat). The African taxis, actually ten-passenger vans, clog the city streets hawking for business and owning the road. Women carry grocery bags on their heads and kids on their backs. It’s high energy here and crowded. On day three, I take a city tour recommended by locals. Richard Powell and his Zulu assistant, Sthembiso, of Street Scene Tours treat me to a five-hour tour that costs under $40.00 including lunch. This is not your average tour, but an experience that exposes the beat of African Durban. The pair work as a tag team: Richard explains the city’s layout and history as we pass the colonial landmarks, and Sthembiso describes the African outlook and way of life as we meander through the Zulu markets and Muslim arcades.

On day three, I take a city tour recommended by locals. Richard Powell and his Zulu assistant, Sthembiso, of Street Scene Tours treat me to a five-hour tour that costs under $40.00 including lunch. This is not your average tour, but an experience that exposes the beat of African Durban. The pair work as a tag team: Richard explains the city’s layout and history as we pass the colonial landmarks, and Sthembiso describes the African outlook and way of life as we meander through the Zulu markets and Muslim arcades.

Since Durban was settled, the large East Indian population has offered its traditional dishes all over the city. Their most famous is Bunny Chow. The Indians who caddied at the Royal Durban Golf Club never had time to stop for lunch, so Mr. Bunny created a unique curry sandwich they could munch on the go. He scooped out the centre of half a loaf, filled the hole with a spicy curry, and stuffed the bread back on top. I eat mine with my fingers, mopping up the hot sauce with pieces of bread and loving it.

Since Durban was settled, the large East Indian population has offered its traditional dishes all over the city. Their most famous is Bunny Chow. The Indians who caddied at the Royal Durban Golf Club never had time to stop for lunch, so Mr. Bunny created a unique curry sandwich they could munch on the go. He scooped out the centre of half a loaf, filled the hole with a spicy curry, and stuffed the bread back on top. I eat mine with my fingers, mopping up the hot sauce with pieces of bread and loving it. The thatched Hilltop Lodge overlooks a wide valley and is blessed with all the amenities of an excellent hotel, including delicious breakfast and dinner buffets. As I push open the door of our roomy cottage, my first sight is a warning about marauding baboons – the robust grills over our windows speak volumes. Harmless Vervet monkeys gambol all around us.

The thatched Hilltop Lodge overlooks a wide valley and is blessed with all the amenities of an excellent hotel, including delicious breakfast and dinner buffets. As I push open the door of our roomy cottage, my first sight is a warning about marauding baboons – the robust grills over our windows speak volumes. Harmless Vervet monkeys gambol all around us. Abruptly the park ranger stops and points out a couple of Nyala (antelope) on a distant slope. Even with binoculars I can barely see them – is this as close as we will get to the game? Then over the next rise, a Black Rhino grazes not 50 feet away. We turn another corner and nearly run into a giraffe. After that, the game appears thick, fast, and close until the sun sets. But the best comes after dark, when we disturb a lion lying in the middle of the trail. He hightails into the bush but stops ten feet away and, with the aid of a spotlight, I can count his teeth when he yawns.

Abruptly the park ranger stops and points out a couple of Nyala (antelope) on a distant slope. Even with binoculars I can barely see them – is this as close as we will get to the game? Then over the next rise, a Black Rhino grazes not 50 feet away. We turn another corner and nearly run into a giraffe. After that, the game appears thick, fast, and close until the sun sets. But the best comes after dark, when we disturb a lion lying in the middle of the trail. He hightails into the bush but stops ten feet away and, with the aid of a spotlight, I can count his teeth when he yawns.

Marrakech is a spectacle of exotica. On a recent eight-day tour, I stayed at the enchanting old Hotel du Foucald, which is well situated for sightseeing in Marrakesch’s medina (old town). The hotel is just across from the famous Djamaa el Fna square with its labyrinth of side streets, hammams, caravanserai and bazaars. The souq is a maze of tiny covered walkways where everything is sold from embroidered saddles for camels, to potions for casting spells. On the bustling streets, donkeys are everywhere, some loaded with produce, others with pottery, some pulling carts heaped with mint for tea. The donkeys wear shoes made from car tires to keep them from sipping on the cobblestones. Weavers and coppersmiths work their trades. Herb doctors assure us their products are better than Viagra. You can buy almost any unusual medicine: goat hooves for hair treatment, ground up ferret for depression , and dried fox heads to use for magic potions.

Marrakech is a spectacle of exotica. On a recent eight-day tour, I stayed at the enchanting old Hotel du Foucald, which is well situated for sightseeing in Marrakesch’s medina (old town). The hotel is just across from the famous Djamaa el Fna square with its labyrinth of side streets, hammams, caravanserai and bazaars. The souq is a maze of tiny covered walkways where everything is sold from embroidered saddles for camels, to potions for casting spells. On the bustling streets, donkeys are everywhere, some loaded with produce, others with pottery, some pulling carts heaped with mint for tea. The donkeys wear shoes made from car tires to keep them from sipping on the cobblestones. Weavers and coppersmiths work their trades. Herb doctors assure us their products are better than Viagra. You can buy almost any unusual medicine: goat hooves for hair treatment, ground up ferret for depression , and dried fox heads to use for magic potions. The busy Djmaa el Fna is a magic world of snake charmers, musicians, acrobats, water vendors wearing distinctive red suits and wide-brimmed hats and jangling bells, story tellers, ebony-skinned dancers in brightly hued costumes, boys with pet monkeys, and other assorted side-show attractions will entertain you — for a price. Don’t try to take photos of these colourful entrepreneurs without expecting to pay, and make sure you only pay no more than five dirham. Once you know your way around and have a feel for the place, it’s fun, and during the day not dangerous to wander on your own.

The busy Djmaa el Fna is a magic world of snake charmers, musicians, acrobats, water vendors wearing distinctive red suits and wide-brimmed hats and jangling bells, story tellers, ebony-skinned dancers in brightly hued costumes, boys with pet monkeys, and other assorted side-show attractions will entertain you — for a price. Don’t try to take photos of these colourful entrepreneurs without expecting to pay, and make sure you only pay no more than five dirham. Once you know your way around and have a feel for the place, it’s fun, and during the day not dangerous to wander on your own. After a morning of touring the historic sites, I took a calèche (horse-drawn carriage) to the Jardin Majorelle in the European quarter. This beautiful garden estate was created in the 1920s by the French Orientalist painter Jacques Majorelle and is now owned by fashion designer Yves St. Laurent. It’s a tropical paradise of tall cacti and palms set against pink towered buildings and grill-worked gateways. Bougainvillea, hibiscus and flowering potted plants line the cobbled pathways. The colours of the buildings and clay pots are dazzling brilliant blue, turquoise, pink, yellow, and orange, all complimenting the colours of the flowers. Birds twitter in the trees and trellises hang with flowering vines. Many different tropical plants grow in abundance. The artist’s studio has been converted into a small Museum of Islamic art and displays St. Laurent’s fine collection of North African carpets and furniture as well as Majorelle’s paintings.

After a morning of touring the historic sites, I took a calèche (horse-drawn carriage) to the Jardin Majorelle in the European quarter. This beautiful garden estate was created in the 1920s by the French Orientalist painter Jacques Majorelle and is now owned by fashion designer Yves St. Laurent. It’s a tropical paradise of tall cacti and palms set against pink towered buildings and grill-worked gateways. Bougainvillea, hibiscus and flowering potted plants line the cobbled pathways. The colours of the buildings and clay pots are dazzling brilliant blue, turquoise, pink, yellow, and orange, all complimenting the colours of the flowers. Birds twitter in the trees and trellises hang with flowering vines. Many different tropical plants grow in abundance. The artist’s studio has been converted into a small Museum of Islamic art and displays St. Laurent’s fine collection of North African carpets and furniture as well as Majorelle’s paintings. Later I got a sense of what it would be like to live in a Moroccan home when I visited the Maison Tiskiwin, a 19th century house once the home of a Dutch anthropologist. It now houses a stunning collection of jewellery, clothes, fabrics and carpets. Houses in Marrakech are windowless, with rooms opening to a sun-lit inner courtyard; the walls hung with woven tapestries and floors paved with lapis and turquoise tiles.

Later I got a sense of what it would be like to live in a Moroccan home when I visited the Maison Tiskiwin, a 19th century house once the home of a Dutch anthropologist. It now houses a stunning collection of jewellery, clothes, fabrics and carpets. Houses in Marrakech are windowless, with rooms opening to a sun-lit inner courtyard; the walls hung with woven tapestries and floors paved with lapis and turquoise tiles.