by Karen Pacheco

Our photo club group reaches Summerland, British Columbia, for some destination photography. We corkscrew up a rural road to reach our accommodations at Wildhorse Mountain Ranch B and B where a welcome party of three enthusiastic canines greets us. Unloaded and settled into our rooms, our itinerary unfolds.

On day one we head to Summerland’s Ornamental Gardens followed in the afternoon by a scheduled steam train ride. While at the gardens we are teased by a glimpse of the seventy-three-metre high Trout Creek Trestle Railway Bridge. Touted as an engineering triumph when it was built in 1913, it’s B.C.’s highest railway trestle and the third highest in North America.

On day one we head to Summerland’s Ornamental Gardens followed in the afternoon by a scheduled steam train ride. While at the gardens we are teased by a glimpse of the seventy-three-metre high Trout Creek Trestle Railway Bridge. Touted as an engineering triumph when it was built in 1913, it’s B.C.’s highest railway trestle and the third highest in North America.

Regrettably, the steam train no longer crosses that trestle. But thanks to an active heritage society and to multi-level government funding, it chugs along a preserved ten-kilometre track from the Prairie Valley Railway Station through to Canyon View Siding. And we learned later that the train does back onto the bridge for viewing and photography.

After lunch we press on towards the Kettle Valley Steam Railway to make our 1:30 reservation.

Departure time will be slightly delayed we’re told. But the reason for the delay–a movie crew filming a period piece with actors dressed in early 20th century attire, delivers photo ops. That, and the chronicled history and features inside and out the train station, keep us reading and keep our cameras clicking.

Departure time will be slightly delayed we’re told. But the reason for the delay–a movie crew filming a period piece with actors dressed in early 20th century attire, delivers photo ops. That, and the chronicled history and features inside and out the train station, keep us reading and keep our cameras clicking.

Uncovering the raison-d’etre for this little railway south of the CPR mainline, becomes a pursuit. Why was Andrew McCulloch, chief engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railway, (CPR) tasked with building the Coast-to-Kootenay Railway? Canada’s most westerly province, British Columbia, had already been enticed to join Canadian Confederation in 1871 by Prime Minister John A. MacDonald’s promise to build a railway from Montreal to the west. However, the CPR mainline completed in 1885, was too far north to transport the Okanagan’s fruit and the Southwest’s newly discovered silver. Canada’s western ports of New Westminster and Vancouver were being left out of the ‘silver’ loop. No cross border protections existed at that time, so Americans were seizing the mineral wealth and transporting it south to connect with the United States’ Great Northern Railway. All this factored in to the CPR directors’ sanctioning the construction of this new line.

“All aboard!” Our reading is interrupted by a robust-voiced conductor. The movie crew concluded their shoot and we now eagerly line up to board. Authentic period-costumed folks––conductor, engineer, and Felix, a charismatic banjo player, along with a team of friendly volunteers, welcome you as you set foot onto the train. For photo enthusiasts, it’s an easy choice between two seating options–open-sided wagons or 1950’s vintage closed coaches. Our eager group scurries to the last open car. After achieving the best viewing spots, we agree to switch sides for the return ride. Once settled in, our journey powered by 2-8-0 steam locomotive 3716, ‘The Spirit of Summerland’ commences.

Built in 1912, the N2 B Class locomotive was said to be “under boilered” as its two engines could consume steam faster than the fireman could make it! The two engines designation came about as each set of cylinders and rods in this cleverly designed locomotive could work independently should there be a malfunction. Locomotive 3716 has a back-up diesel engine–the 1956 S6, 115-ton, 6 cylinder 2S1B Prime Mover. While our group chose the more modern open air coach, the enclosed, restored 1940’s vintage coaches, would be a better choice for cooler, inclement weather, especially the seasonal Christmas Train Ride.

Dressed to match the times, Felix, a delightful banjo-playing songster, kicks off in our section with some classic favourites, ‘I’ve Been Working on the Railroad’ and ‘You are my Sunshine’. Requests are welcomed as he wanders through the cars. And he can pretty much play any tune asked for. Conductor Ron, provides educational and humourous commentary as we snake along the route.

Dressed to match the times, Felix, a delightful banjo-playing songster, kicks off in our section with some classic favourites, ‘I’ve Been Working on the Railroad’ and ‘You are my Sunshine’. Requests are welcomed as he wanders through the cars. And he can pretty much play any tune asked for. Conductor Ron, provides educational and humourous commentary as we snake along the route.

We weave around pine forests opening onto the fertile Prairie Valley. There unfold views of vineyards, wineries, and orchards. The proximity of carved slabs of colossal rock remind us of the challenges faced by McCulloch’s crew. A repetitive metal on metal cadence of the wheels on tracks blend with the engine’s din. Billowing smoke from the stack emits an acrid odour, completing the retro sensory experience.

Shrill whistle sequences signal the stop at Trout Creek Canyon. Here we disembark for the grand view, a leg stretch and more photos, of course. Accommodating, patient crew pose with passengers while other folks dart around the train snapping images of the locomotive and valley from different angles. Again, the whistle signals, this time for us to board for the return trip. We change sides, relax as veteran passengers now, and take in the landscape.

Shrill whistle sequences signal the stop at Trout Creek Canyon. Here we disembark for the grand view, a leg stretch and more photos, of course. Accommodating, patient crew pose with passengers while other folks dart around the train snapping images of the locomotive and valley from different angles. Again, the whistle signals, this time for us to board for the return trip. We change sides, relax as veteran passengers now, and take in the landscape.

Having served a timely purpose, the little rail line that could, five hundred kilometres traversing three mountain ranges, came to an end due to air and vehicle transportation advancements and to unforgiving winters taking their toll.

The Kettle Valley Steam Railway experience not only has regular trips, but also offers the ‘Great Train Robbery and BBQ’, an Easter and Mother’s Day train. Regular season starts the third week of May.

Leaving Prairie Valley Station at the journeys end, we feel thankful that the folks in the heritage society took on the initiative to preserve this gem of Canadian railway history.

If You Go:

To plan your trip and book your tickets, visit the comprehensive Kettle Valley Railway website.

Beat the Bottleneck: Summerland Full-Day Wine Tour

About the author:

Karen is an award-winning photographer, CAPA (Canadian Association for Photographic Art) District Representative, and past president of the Delta Photo Club. When her thirty-year career as an educator ended, she was able to focus more time on her passions of photography, travel and writing.

All photos by Karen Pacheco

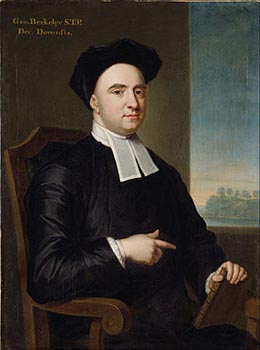

Counterintuitive as the view may be, it was endorsed by Berkeley as an answer to skeptical doubts about the possibility of knowledge. How do we know that the world actually resembles our ideas and perceptions of it? Worse yet, how do we know that the things we perceive really exist? (We are all familiar with hallucinations; can we be sure that all perception is not like that?) For Berkeley, the solution was to deny that matter exists independently of the mind. We can be sure that things in the world really are as they appear to us, he reasoned, only if material objects just are ideas in our minds. Hence Berkeley’s famous slogan “to be is to be perceived.”

Counterintuitive as the view may be, it was endorsed by Berkeley as an answer to skeptical doubts about the possibility of knowledge. How do we know that the world actually resembles our ideas and perceptions of it? Worse yet, how do we know that the things we perceive really exist? (We are all familiar with hallucinations; can we be sure that all perception is not like that?) For Berkeley, the solution was to deny that matter exists independently of the mind. We can be sure that things in the world really are as they appear to us, he reasoned, only if material objects just are ideas in our minds. Hence Berkeley’s famous slogan “to be is to be perceived.”

Neon put the “fabulous” in “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas.” And Vegas was surely at its fabulous peak in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. The “Rat Pack”- Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop and Sammy Davis, Jr. and other big name entertainers along with the casinos lured visitors by the thousands to the desert. Light it up and they will come. And light it they did. Vegas became a super nova of light – a dazzling showcase of the entertainment world with its iconic signs like the Vegas Vic, the waving, smoking cowboy, the exotic camels of the Sahara, and the classy star-studded Riviera.

Neon put the “fabulous” in “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas.” And Vegas was surely at its fabulous peak in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. The “Rat Pack”- Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop and Sammy Davis, Jr. and other big name entertainers along with the casinos lured visitors by the thousands to the desert. Light it up and they will come. And light it they did. Vegas became a super nova of light – a dazzling showcase of the entertainment world with its iconic signs like the Vegas Vic, the waving, smoking cowboy, the exotic camels of the Sahara, and the classy star-studded Riviera. Las Vegas Neon Museum

Las Vegas Neon Museum

But other historical neon signs have also found their way to the neon boneyard, with their own fascinating stories to tell like El Portal, the first theater and luxury movie palace established in the city of Las Vegas in 1928 on downtown’s Fremont Street. The Green Shack was Vegas’ longest operating restaurant built in the early thirties, catering to Hoover Dam’s construction workers and suppliers. The restaurant was famous for its chicken, steaks and bootleg whisky during Prohibition.

But other historical neon signs have also found their way to the neon boneyard, with their own fascinating stories to tell like El Portal, the first theater and luxury movie palace established in the city of Las Vegas in 1928 on downtown’s Fremont Street. The Green Shack was Vegas’ longest operating restaurant built in the early thirties, catering to Hoover Dam’s construction workers and suppliers. The restaurant was famous for its chicken, steaks and bootleg whisky during Prohibition.